Stanford, CA – Imagine a world where a vaccine is applied as a cream rather than administered through a needle. This vision may soon become a reality thanks to researchers at Stanford University who have developed a topical vaccine using a common skin bacterium, Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Michael Fischbach, Ph.D., the Liu (Liao) Family Professor and professor of bioengineering at Stanford, explained the potential of this innovative approach. “We all hate needles—everybody does. I haven’t found a single person who doesn’t like the idea that it’s possible to replace a shot with a cream,” Fischbach said.

Despite the harsh conditions of the skin, a few hardy microbes call it home, including S. epidermidis. These bacteria reside on nearly every hair follicle of virtually every person on the planet. Fischbach and his colleagues discovered that the immune system mounts a robust response against S. epidermidis, producing antibodies that could be harnessed for vaccination.

In a study published in Nature, Fischbach and his team demonstrated that mice exposed to S. epidermidis developed high levels of antibodies, similar to those produced by traditional vaccinations. Remarkably, human blood samples showed that circulating antibodies against S. epidermidis were as high as those for routine vaccinations.

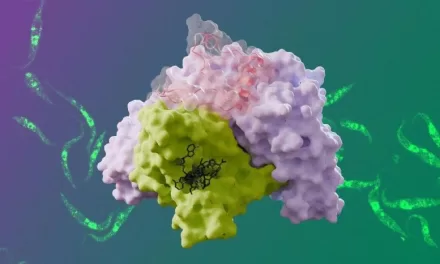

This strong immune response led the researchers to explore the potential of turning S. epidermidis into a living vaccine. They identified a protein called Aap on the bacterium’s surface as a key trigger for the immune response. By engineering S. epidermidis to display harmless fragments of tetanus and diphtheria toxins, they created a version that induced specific antibody responses in mice.

The modified bacteria generated enough antibodies to protect mice from lethal doses of tetanus and diphtheria toxins. The researchers also found that the presence of S. epidermidis on the skin did not interfere with the vaccine’s effectiveness.

Fischbach and his team plan to test this approach in monkeys next, with the goal of entering clinical trials within two to three years. “We think this will work for viruses, bacteria, fungi, and one-celled parasites,” Fischbach said. “Most vaccines have ingredients that stimulate an inflammatory response and make you feel a little sick. These bugs don’t do that. We expect that you wouldn’t experience any inflammation at all.”

This breakthrough could revolutionize the way vaccines are administered, offering a painless, effective, and accessible alternative to traditional injections.

For more information, see the original study: Discovery and engineering of the antibody response to a prominent skin commensal, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08489-4.

Journal information: Nature.