Barcelona, Spain — Groundbreaking research led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), in collaboration with several African research centers, has revealed that maternal antibodies transferred across the placenta may significantly interfere with the immune response to malaria vaccines in infants under five months old. The findings, published in Lancet Infectious Diseases, shed light on why the RTS,S and R21 malaria vaccines show lower efficacy in this age group and suggest that these vaccines could potentially be beneficial for younger infants in specific low malaria transmission areas.

Malaria remains a significant health threat in Africa, with the two malaria vaccines, RTS,S/AS01E and R21/Matrix-M, recently rolled out to protect children against the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. These vaccines are currently recommended for children aged five months or older.

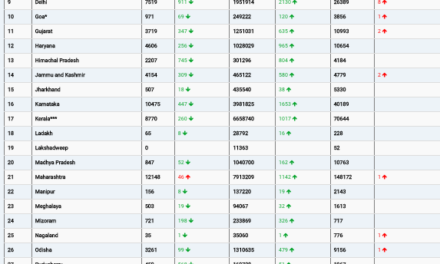

Carlota Dobaño, head of the Malaria Immunology group at ISGlobal, stated, “We know that the RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine is less effective in infants under five months of age, but the reason for this difference is still debated.” To address this question, Dobaño and her team analyzed blood samples from over 600 children aged 5 to 17 months and infants aged 6 to 12 weeks, all participants in a phase 3 clinical trial of RTS,S/AS01E.

Using advanced protein microarrays, researchers measured the levels of antibodies against approximately 1,000 P. falciparum antigens prior to vaccination, allowing them to assess how malaria exposure and age influenced antibody responses to the malaria vaccine. The results were illuminating.

The study found that infants who received the vaccine had significantly reduced responses if they had high levels of maternal antibodies to P. falciparum, particularly anti-CSP (circumsporozoite protein) antibodies. This interference was not observed in older children who had developed their immune responses through natural infections.

“While maternal antibodies can provide important protection to infants, our findings indicate that they may also hinder the effectiveness of vaccination in the earliest months of life,” explained Didac Maciá, an ISGlobal researcher and the study’s first author.

Maternal antibodies typically peak in infants during the first three months due to passive transfer during pregnancy, then decline over the first year, followed by a natural increase in response to infections. In regions of higher malaria transmission, mothers transmit more antibodies to their infants, which may correlate with reduced vaccine efficacy.

“Our study highlights the need to consider timing and maternal malaria antibody levels to improve vaccine efficacy for the youngest and most vulnerable infants,” noted Gemma Moncunill, co-senior author of the study.

The implications of this research could be profound. If infants under five months in low malaria transmission settings could safely receive the RTS,S or R21 vaccines, it may provide crucial protection during critical developmental periods.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, through grants R01AI095789 and U01AI165745. As the global fight against malaria continues, understanding the nuances of vaccine efficacy in vulnerable populations remains paramount.