BERLIN — What’s the best strategy to help patients with diabetes, heart problems, and obesity lose weight and improve their outcomes? Should they prioritize exercise or medication, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 or gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor agonists? This debate was at the heart of a “Battle of Experts” at the 2024 Diabetes Congress in Berlin.

Benefits of Exercise

“Exercise is ‘omnipotent,'” declared Dr. Christine Joisten, a general, sports, and nutrition physician at the Sports University in Cologne, Germany. She highlighted that exercise not only aids in weight loss but also enhances overall fitness, body composition, eating habits, cardiometabolic health, and quality of life.

In an interview with Medscape’s German edition, Dr. Stephan Kress, a diabetologist at Vinzentius Hospital in Landau, Germany, referenced a study by Pedersen et al., which examined the impact of exercise on 26 conditions. The study found that exercise had moderate to strong positive effects on disease progression, benefiting conditions beyond metabolic, cardiological, pneumological, and musculoskeletal diseases, extending to neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bente Klarlund Pedersen of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark, explained that myokines—beneficial cytokines released by muscles—could play a role in these benefits. For instance, exercise can elevate mood in patients with depression and reduce inflammation in those with chronic inflammatory diseases. Kress emphasized that many patients, including those with diabetes, could benefit from physical activity even if their HbA1c levels do not decrease as desired.

Exercise as a Snack

Dr. Joisten explained that fat loss could be achieved through prolonged activity or “short and intense” sessions if followed by refraining from eating immediately afterward. She noted that even minor activities like standing up, walking around, climbing stairs, and everyday movements can help motivate patients with obesity. Joisten emphasized that exercise offers significant health benefits, starting from the initial stages of physical activity.

Adding just 500 more steps per day can reduce cardiovascular mortality by 7%, while an additional 1000 steps daily decreases overall mortality by 15%, according to a recent meta-analysis. For those confined to spaces like a home office, “exercise snacks”—short bursts of movement throughout the day—are recommended.

Kress supported this approach, advising lower intensity but longer duration activities for greater benefits. He recommended “walking without panting,” like walking or jogging at a conversational pace. Even the first walk can improve coronary artery conditions, and fragmented exercise sessions, such as three 10-minute walks per day, can enhance circulation and fitness. Moderate aerobic training is also effective for fat burning and preventing lactic acid buildup.

The Next Step

Gradual progression to longer or brisker walks is suggested, though the goal does not always have to be 10,000 steps per day. A meta-analysis presented by Joisten found that 8000-10,000 steps daily significantly reduced mortality in individuals under 60 years old, while 6000-8000 steps were sufficient for those over 60.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends 150-300 minutes of exercise per week for adults, including seniors, which equates to 30-60 minutes per day, five days a week. Strength training is also recommended twice a week, or three days of combined strength and balance training for seniors.

A network meta-analysis compared various exercise regimens for overweight or obese individuals:

- Interval training (very high intensity, 2-3 days/week, averaging 91 minutes/week)

- Strength training (2-3 days/week, averaging 126 minutes/week)

- Continuous endurance training (moderate intensity, 3-5 days/week, averaging 176 minutes/week)

- Combined training (3-4 days/week, averaging 187 minutes/week)

- Hybrid training (high intensity, such as dancing, jumping rope, ball sports, etc., 2-3 days/week, averaging 128 minutes/week).

The combined training group, which included the longest weekly training times, showed the best results in all five endpoints: body composition, blood lipid levels, blood sugar control, blood pressure, and cardiorespiratory fitness. However, hybrid training also produced good outcomes.

First, Visit the Doctor

Patients who wish to start exercising, especially those with cardiac-respiratory or orthopedic conditions, should undergo a medical checkup first, advised Kress. In most cases, a stationary bicycle test at the primary care physician’s office is sufficient. For higher athletic goals, consultation with a sports physician or cardiologist is recommended.

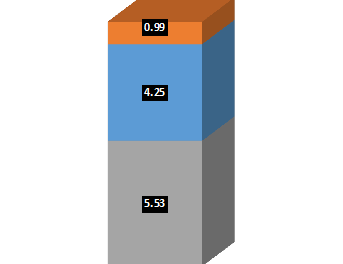

However, Joisten pointed out that when it comes to weight loss alone, exercise may not be very effective. A meta-analysis showed that exercise could lead to a weight loss of approximately 1.5-3.5 kg, with about 1.3-2.6 kg being fat mass and only 330-560 g being visceral fat, which is the most significant type.

A Direct Comparison

Dr. Matthias Blüher, an endocrinologist and diabetologist at the University Hospital Leipzig in Leipzig, Germany, represented the pro-injection position. He presented a study by Lundgren et al., which showed that treatment with 3.0 mg/day liraglutide was significantly more effective for weight loss than moderate to intensive physical activity. After 12 months, patients on the injection lost 6.8 kg, while those who exercised lost only 4.1 kg. “The injection wins in a direct comparison,” Blüher stated.

Blüher also highlighted the risk of injury associated with exercise, noting that patients may become less active after a sports injury. The LOOK-AHEAD study investigated whether a lifestyle program involving exercise and dietary changes brought cardiovascular benefits but found that patients regained weight over time, and the combined cardiovascular endpoint did not differ between the active lifestyle group and the inactive control group.

The SELECT study compared the effect of once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo on cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular conditions and overweight or obesity. Patients in the semaglutide group had significantly fewer cardiovascular events over nearly three years than those in the placebo group (6.5% vs 8.0%). Although the study participants did not have diabetes, two-thirds had prediabetes with relatively high baseline HbA1c levels. Semaglutide significantly delayed the onset of diabetes in these patients, Blüher reported.

A review involving Blüher found that treatment with 2.4 mg semaglutide or 15 mg tirzepatide over 12 months was more effective than many older medications (including orlistat) but not as effective as bariatric surgery. Participants in the Exercise and Nutrition study performed worse than those on older medications.

Combination Therapy

Blüher and Joisten agreed that combining exercise with incretin-based medications yields the best results for weight loss and blood sugar control. For instance, data from the Lundgren study showed that participants combining liraglutide with exercise lost an average of 9.5 kg. Additionally, their HbA1c levels, insulin sensitivity, and cardiorespiratory fitness improved significantly.

During the audience discussion, interval therapy—alternating between exercise and injections—gained widespread approval. Kress supported this idea, noting that it could minimize costs and enhance insurance companies’ acceptance of the therapy. He emphasized that exercise should not be interrupted, suggesting that patients might not want breaks, hoping that “once someone has lost weight (even under injection therapy), they gain new motivation to move and achieve more.”