For centuries, European folklore has propagated the belief that the common adder (Vipera berus), known for its painful but rarely lethal bite, harbors greater danger in its melanistic (fully black) form, earning the nickname “hell adder.” However, recent research published in Royal Society Open Science reveals that the venom of these dark-colored adders is not significantly more toxic than their multihued counterparts, challenging long-held superstitions.

Tim Lüddecke, a biochemist and zoologist at the Fraunhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology, and corresponding author of the study, emphasizes that the common adder is one of the most geographically successful snakes, thriving in various habitats across Europe and East Asia. This adaptability, especially in cold climates, sets it apart—it’s one of only two venomous snakes in Germany and the only snake known to live north of the Arctic Circle.

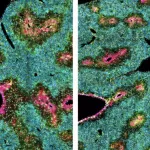

Most adders exhibit a brown or gray coloration with a distinct zigzag pattern, which aids in camouflage. In contrast, melanistic adders, although more visible to predators, have an advantage in cold weather due to their ability to absorb more heat. Lüddecke notes that folklore often associates black animals with sinister forces, leading to unnecessary fear and persecution of these snakes.

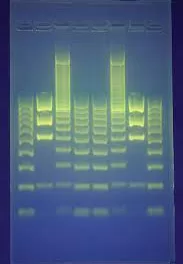

The research team, led by Lennart Schulte, a venomics researcher, analyzed venom samples from nine melanistic and nine normally colored adult male adders. While the venoms contained similar molecular components, the study found that the black adders had slightly higher levels of proteases—enzymes that can break down proteins—making their venom marginally more toxic to living cells at specific concentrations. However, these differences were minimal and unlikely to impact the severity of bites, which typically deliver 10 to 18 milligrams of venom.

Despite the intriguing findings, the study’s limitations include its focus on captive snakes. Timothy Jackson, an evolutionary toxinologist at the University of Melbourne, notes that environmental factors in the wild could influence venom toxicity further. For instance, melanistic adders breed and emerge earlier than their multicolored peers, potentially affecting venom composition due to temperature variations.

Looking ahead, Lüddecke and Schulte aim to continue their research into venom variation within snake species, ultimately working towards developing more effective antivenoms. They also hope to dispel the myth surrounding hell adders, advocating for the protection and study of all snake varieties.

As public perception shifts, this research underscores the importance of understanding the biological realities of these reptiles rather than succumbing to age-old superstitions. The findings not only challenge misconceptions but also highlight the need for conservation efforts amidst declining adder populations due to habitat destruction.

Conclusion

The common adder, often feared for its rumored venomous potency, is a testament to the adage that appearances can be deceiving. By shedding light on the nuances of snake venom and addressing cultural myths, scientists hope to foster a greater appreciation for the biodiversity of these misunderstood creatures.