San Diego, CA – A groundbreaking study led by bioengineers at the University of California San Diego has uncovered a crucial link between a gene on the Y chromosome and the differing progression of aortic valve stenosis (AVS) in men and women. The research, published in Science Advances, sheds light on how sex chromosomes influence disease development and opens the door for tailored treatments based on biological sex.

Aortic valve stenosis, a life-threatening condition where the heart’s aortic valve stiffens, has long been observed to manifest differently in males and females. Males tend to develop early calcium buildup in the valve, while females experience stiffening due to fibrotic tissue formation.

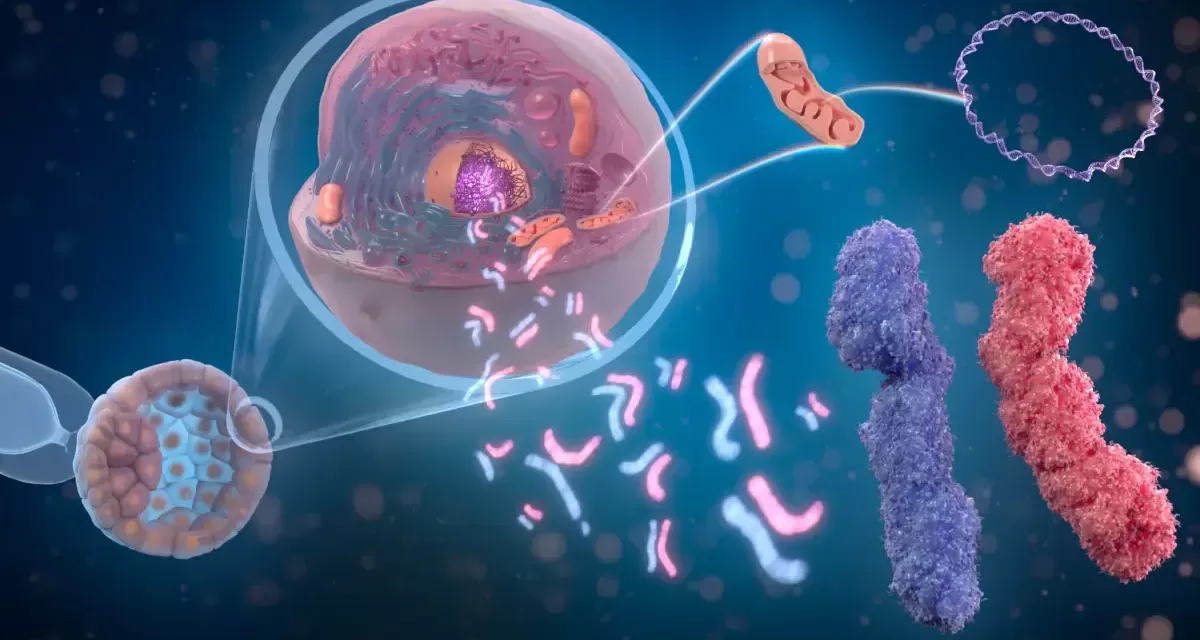

The new study identifies the UTY gene, located on the Y chromosome, as a key driver of valve calcification in males. Researchers used a specially engineered hydrogel, mimicking the microenvironment of aortic valve tissue, to cultivate male and female heart valve cells. This approach revealed distinct sex-based differences in cellular behavior, which were absent in standard Petri dish cultures.

“Our research is showing that we need to look at your chromosome makeup to figure out the best treatment for you. The one-size-fits-all approach often does not work,” stated Professor Brian Aguado, senior author of the study.

The researchers discovered that in males, valvular interstitial cells differentiate into bone-like cells that generate calcium nanoparticles, leading to valve calcification. This process is significantly influenced by the UTY gene.

“This study highlights the importance of digging into the sexual dimorphism that’s seen in aortic valve stenosis,” said Rayyan Gorashi, the study’s first author. “Since the molecular pathways driving this disease are different in males and females, understanding these sex-based mechanisms can allow us to create sex-specific treatment options for patients down the line.”

The team’s findings underscore the need to consider sex as a biological variable in disease research and treatment. Future work will focus on exploring potential drug targets for the UTY gene and developing therapies tailored to the specific mechanisms of AVS in males and females.

“By figuring out these sex-dependent mechanisms, we can develop therapies that are more effective for all people,” Aguado concluded.

Disclaimer: This article is based on information provided in the referenced research study. Further research and clinical trials are necessary to validate these findings and develop effective treatments. The information presented here should not be interpreted as medical advice. Consult with a healthcare professional for any health concerns.