World Malaria Day 2023 will be marked under the theme “Time to deliver zero malaria: invest, innovate, implement”. Within this theme, WHO will focus on the third “i” – implement – and notably the critical importance of reaching marginalized populations with the tools and strategies that are available today.

Key facts

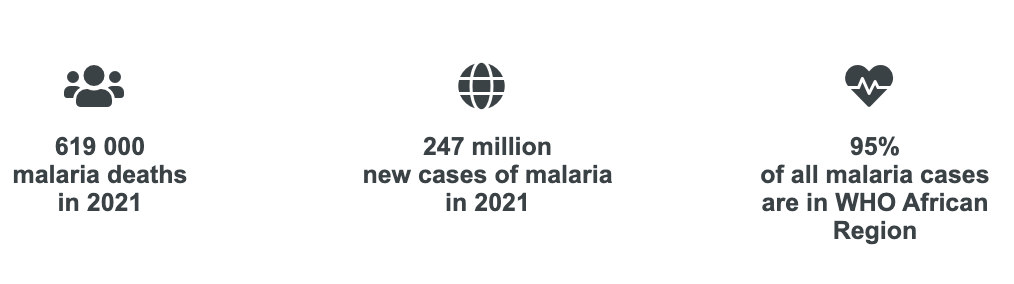

- In 2021, nearly half of the world’s population was at risk of malaria.

- That year, there were an estimated 247 million cases of malaria worldwide.

- The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 619 000 in 2021.

- The WHO African Region carries a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden. In 2021, the Region was home to 95% of malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths. Children under 5 accounted for about 80% of all malaria deaths in the Region.

Overview

Malaria is a life-threatening disease spread to humans by some types of mosquitoes. It is mostly found in tropical countries. It is preventable and curable.

Symptoms can be mild or life-threatening. Mild symptoms are fever, chills and headache. Severe symptoms include fatigue, confusion, seizures, and difficulty breathing.

Infants, children under 5 years, pregnant women, travellers and people with HIV or AIDS are at higher risk of severe infection.

Malaria can be prevented by avoiding mosquito bites and with medicines. Treatments can stop mild cases from getting worse.

Malaria mostly spreads to people through the bites of some infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Blood transfusion and contaminated needles may also transmit malaria. The first symptoms may be mild, similar to many febrile illnesses, and difficulty to recognize as malaria. Left untreated, P. falciparum malaria can progress to severe illness and death within 24 hours.

There are 5 Plasmodium parasite species that cause malaria in humans and 2 of these species – P. falciparum and P. vivax – pose the greatest threat. P. falciparum is the deadliest malaria parasite and the most prevalent on the African continent. P. vivax is the dominant malaria parasite in most countries outside of sub-Saharan Africa. The other malaria species which can infect humans are P. malariae, P. ovale and P. knowlesi.

Symptoms

The most common early symptoms of malaria are fever, headache and chills.

Symptoms usually start within 10–15 days of getting bitten by an infected mosquito.

Symptoms may be mild for some people, especially for those who have had a malaria infection before. Because some malaria symptoms are not specific, getting tested early is important.

Some types of malaria can cause severe illness and death. Infants, children under 5 years, pregnant women, travellers and people with HIV or AIDS are at higher risk. Severe symptoms include:

- extreme tiredness and fatigue

- impaired consciousness

- multiple convulsions

- difficulty breathing

- dark or bloody urine

- jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin)

- abnormal bleeding.

People with severe symptoms should get emergency care right away. Getting treatment early for mild malaria can stop the infection from becoming severe.

Malaria infection during pregnancy can also cause premature delivery or delivery of a baby with low birth weight.

Disease burden

According to the latest World malaria report, there were 247 million cases of malaria in 2021 compared to 245 million cases in 2020. The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 619 000 in 2021 compared to 625 000 in 2020.

Over the 2 peak years of the pandemic (2020–2021), COVID-related disruptions led to about 13 million more malaria cases and 63 000 more malaria deaths. The WHO African Region continues to carry a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden. In 2021 the Region was home to about 95% of all malaria cases and 96% of deaths. Children under 5 years of age accounted for about 80% of all malaria deaths in the Region.

Four African countries accounted for just over half of all malaria deaths worldwide: Nigeria (31.3%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12.6%), United Republic of Tanzania (4.1%) and Niger (3.9%).

Prevention

Malaria can be prevented by avoiding mosquito bites or by taking medicines. Talk to a doctor about taking medicines such as chemoprophylaxis before travelling to areas where malaria is common.

Lower the risk of getting malaria by avoiding mosquito bites:

- Use mosquito nets when sleeping in places where malaria is present

- Use mosquito repellents (containing DEET, IR3535 or Icaridin) after dusk

- Use coils and vaporizers.

- Wear protective clothing.

- Use window screens.

Vector control

Vector control is a vital component of malaria control and elimination strategies as it is highly effective in preventing infection and reducing disease transmission. The 2 core interventions are insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS).

Progress in global malaria control is threatened by emerging resistance to insecticides among Anopheles mosquitoes. As described in the latest World malaria report, other threats to ITNs include insufficient access, loss of nets due to the stresses of day-to-day life outpacing replacement, and changing behaviour of mosquitoes, which appear to be biting early before people go to bed and resting outdoors, thereby evading exposure to insecticides.

Chemoprophylaxis

Travellers to malaria endemic areas should consult their doctor several weeks before departure. The medical professional will determine which chemoprophylaxis drugs are appropriate for the country of destination. In some cases, chemoprophylaxis drugs must be started 2–3 weeks before departure. All prophylactic drugs should be taken on schedule for the duration of the stay in the malaria risk area and should be continued for 4 weeks after the last possible exposure to infection since parasites may still emerge from the liver during this period.

Preventive chemotherapies

Preventive chemotherapy is the use of medicines, either alone or in combination, to prevent malaria infections and their consequences. It requires giving a full treatment course of an antimalarial medicine to vulnerable populations at designated time points during the period of greatest malarial risk, regardless of whether the recipients are infected with malaria.

Preventive chemotherapy includes perennial malaria chemoprevention (PMC), seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) and school-aged children (IPTsc), post-discharge malaria chemoprevention (PDMC) and mass drug administration (MDA). These safe and cost-effective strategies are intended to complement ongoing malaria control activities, including vector control measures, prompt diagnosis of suspected malaria, and treatment of confirmed cases with antimalarial medicines.

Vaccine

Since October 2021, WHO recommends broad use of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine among children living in regions with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission. The vaccine has been shown to significantly reduce malaria, and deadly severe malaria, among young children.

Questions and answers on the RTS,S vaccine.

Treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment of malaria reduces disease, prevents deaths and contributes to reducing transmission. WHO recommends that all suspected cases of malaria be confirmed using parasite-based diagnostic testing (through either microscopy or a rapid diagnostic test).

Malaria is a serious infection and always requires treatment with medicine.

Multiple medicines are used to prevent and treat malaria. Doctors will choose one or more based on:

- the type of malaria

- whether a malaria parasite is resistant to a medicine

- the weight or age of the person infected with malaria

- whether the person is pregnant.

These are the most common medicines for malaria:

- Artemisinin-based combination therapy medicines like artemether-lumefantrine are usually the most effective medicines.

- Chloroquine is recommended for treatment of infection with the P. vivax parasite only in places where it is still sensitive to this medicine.

- Primaquine should be added to the main treatment to prevent relapses of infection with the P. vivax and P. ovale parasites.

Most medicines used are in pill form. Some people may need to go to a health centre or hospital for injectable medicines.

Antimalarial drug resistance

Over the last decade, partial artemisinin resistance has emerged as a threat to global malaria control efforts in the Greater Mekong subregion. WHO is very concerned about recent reports of partial artemisinin resistance in Africa, confirmed in Eritrea, Rwanda and Uganda. Regular monitoring of antimalarial drug efficacy is needed to inform treatment policies in malaria-endemic countries, and to ensure early detection of, and response to, drug resistance.

For more on WHO’s work on antimalarial drug resistance in the Greater Mekong subregion, visit the Mekong Malaria Elimination Programme webpage. WHO has also developed a strategy to address drug resistance in Africa.

Elimination

Malaria elimination is defined as the interruption of local transmission of a specified malaria parasite species in a defined geographical area as a result of deliberate activities. Continued measures to prevent re-establishment of transmission are required.

In 2021, 35 countries reported fewer than 1000 indigenous cases of the disease, up from 33 countries in 2020 and just 13 countries in 2000. Countries that have achieved at least 3 consecutive years of zero indigenous cases of malaria are eligible to apply for the WHO certification of malaria elimination. Since 2015, 9 countries have been certified by the WHO Director-General as malaria-free, including Maldives (2015), Sri Lanka (2016), Kyrgyzstan (2016), Paraguay (2018), Uzbekistan (2018), Argentina (2019), Algeria (2019), China (2021) and El Salvador (2021).

Countries and territories certified malaria-free by WHO.

Surveillance

Malaria surveillance is the continuous and systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of malaria-related data, and the use of that data in the planning, implementation and evaluation of public health practice. Improved surveillance of malaria cases and deaths helps ministries of health determine which areas or population groups are most affected and enables countries to monitor changing disease patterns. Strong malaria surveillance systems also help countries design effective health interventions and evaluate the impact of their malaria control programmes.

WHO response

The WHO Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030, updated in 2021, provides a technical framework for all malaria-endemic countries. It is intended to guide and support regional and country programmes as they work towards malaria control and elimination.

The strategy sets ambitious but achievable global targets, including:

- reducing malaria case incidence by at least 90% by 2030

- reducing malaria mortality rates by at least 90% by 2030

- eliminating malaria in at least 35 countries by 2030

- preventing a resurgence of malaria in all countries that are malaria-free.

Guided by this strategy, the Global Malaria Programme coordinates the WHO’s global efforts to control and eliminate malaria by:

- playing a leadership role in malaria, effectively supporting member states and rallying partners to reach Universal Health Coverage and achieve goals and targets of the Global Technical Strategy for Malaria;

- shaping the research agenda and promoting the generation of evidence to support global guidance for new tools and strategies to achieve impact;

- developing ethical and evidence based global guidance on malaria with effective dissemination to support adoption and implementation by national malaria programmes and other relevant stakeholders; and

- monitoring and responding to global malaria trends and threats.