For the past three years, the world has been closely monitoring the spread of H5N1 avian influenza, particularly a new variant, clade 2.3.4.4b, which has been wreaking havoc across poultry farms globally. This strain has spread from birds to mammals, including cattle in Texas, and has even led to dozens of human infections in North America. The virus has shown troubling mutations that suggest it could adapt to infect human cells more efficiently. Yet, despite these ominous signs, a full-blown pandemic has not materialized—yet. So why hasn’t the world faced an H5N1 outbreak on the scale of COVID-19?

Experts are divided over whether we are on the precipice of a pandemic or if H5N1 is simply another flu strain that will eventually fizzle out. Louise Moncla, a virologist at the University of Pennsylvania, expressed concern: “If H5 is ever going to be a pandemic, it’s going to be now.” Yet others remain cautious, pointing to similar scares in the past that never evolved into human-to-human transmission. Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins, reminded the public that predicting such events is fraught with uncertainty, noting that we “really can’t estimate” what will happen.

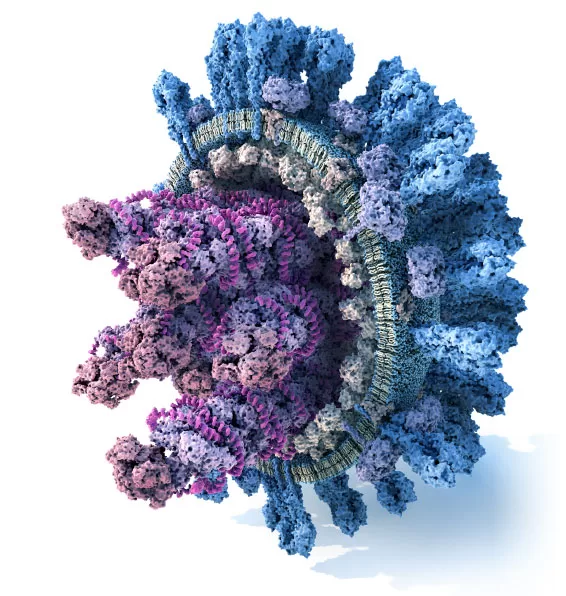

The world’s anxiety stems from the long history of H5N1’s threat to human health. First identified in humans in Hong Kong in 1997, the virus infected 18 people and killed six, primarily those who had close contact with infected poultry. Since then, H5N1 has been consistently monitored for signs of mutations that might allow it to spread efficiently between humans, especially those mutations related to the virus’ polymerase (a key enzyme for viral replication) and hemagglutinin, the protein the virus uses to bind to cells in the human airways.

Recent studies have heightened concerns. Research has shown that the clade 2.3.4.4b virus currently circulating in birds and cattle has an increased ability to bind to human airway cells. Additionally, a recent study found that a single mutation at position 226 in the hemagglutinin protein—long thought to require two mutations—might be enough to make the virus better suited for human infection. Jim Paulson of Scripps Research, a co-author of the study, emphasized that this single mutation “means the likelihood of it happening is higher.”

But despite these findings, a key question remains: Why hasn’t a pandemic occurred yet? Experts point to several factors. One possible explanation is that H5N1 may simply require more time to accumulate the right mutations for efficient human-to-human transmission. Influenza viruses are known for their high mutation rates, which increase the odds of the virus evolving in a way that allows it to jump species. A mutation in the virus’ polymerase has already been observed in mammal infections, and while the key mutation for human transmission—226L—has not appeared, it may just need more time to emerge.

Another possibility is that the current version of H5N1 circulating in birds and cattle might have reached a biological dead end. While researchers have identified mutations that increase the virus’ potential to infect humans, they have not yet seen those mutations lead to widespread human-to-human transmission. A recent case in Canada, involving a teenager infected with the virus, seemed to indicate that the virus might be evolving towards human adaptation. However, it was not the feared 226L mutation that appeared; instead, it was a different amino acid change that could still have the same effect, though the implications remain unclear.

Some scientists, like Richard Webby at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, worry that the ongoing circulation of H5N1 in both birds and mammals—particularly in the newly reassorted bird strain D1.1—may offer the virus a better chance of adapting to humans than the cattle strain currently circulating. Mike Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, also voiced concerns, noting that the D1.1 strain could be more flexible and might be more likely to transform into a pandemic virus.

Ultimately, while researchers are on high alert, they caution that there are still many unknowns. It’s possible that H5N1 has already acquired the necessary mutations but that it simply hasn’t found enough opportunities to spread between humans. Scott Hensley, a viral immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania, explained, “At the end of the day, I think it is a numbers game.” In other words, if more people were exposed to the virus, it could potentially trigger a much larger human outbreak.

For now, the world remains on edge, balancing between vigilance and uncertainty, as the threat of an H5N1 pandemic looms, yet refuses to fully materialize. The virus’ unpredictable nature leaves experts watching closely for signs of further mutations—and hoping for the best, but preparing for the worst.