Researchers at Wayne State University have unveiled groundbreaking findings that establish a connection between male exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and health complications in their offspring. The study, titled “Mixtures of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) alter sperm methylation and long-term reprogramming of offspring liver and fat transcriptome,” recently published in Environment International, explores the impact of PFAS mixtures on sperm methylation and subsequent transcriptional changes in offspring’s metabolic tissues, such as the liver and fat.

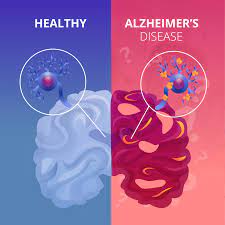

“PFAS research is important, especially in Michigan,” stated Michael C. Petriello, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Department of Pharmacology. “It has been recently in the news since the EPA is finally starting to regulate PFAS chemicals and include them as part of the Clean Water Act. All over the country, communities will have standards they will have to meet. PFAS are associated with many chronic diseases and can impact inflammation and the immune system, for instance. This work is focused on reproductive outcomes, fertility, and offspring metabolism. The idea that exposure of the father could affect the health of offspring is entirely new.”

The significance of these findings lies in their demonstration that a mixture of both legacy and emerging PFAS chemicals in adult male mice leads to abnormal sperm methylation and altered gene expression in the liver and fat of their offspring, with effects varying based on the sex of the offspring. This suggests that preconception exposure to PFAS in males can have transgenerational effects, influencing the phenotype of the next generation.

“Dr. Petriello’s prior work has shown that PFAS exposure has effects on cardio-metabolic health,” noted J. Richard Pilsner, Ph.D., M.P.H., professor of obstetrics and gynecology and associate director of the C.S. Mott Center for Human Growth and Development. “What my research has done is examine paternal exposures and how they may affect the next generation through sperm-related markers. The burden has always been on maternal health during pregnancy in regard to the health of offspring. This research shows that environmental health prior to conception also is a key factor that affects offspring health and development.”

The implications of these findings could reshape how reproductive health is approached, emphasizing the role of male pre-conception health. “I hope these findings promote an appreciation of male health on their offspring’s development,” Pilsner said. “In addition to female partners, clinical doctors advising male partners that their pre-conception health impacts their children’s health would be a significant change to positively impact future generations.”

Ezemenari M. Obasi, Ph.D., vice president for research at Wayne State University, highlighted the broader impact of this research. “This cutting-edge research may have a significant impact on how individuals look at harmful chemicals in their communities, and ultimately how medical professionals advise their patients,” Obasi said. “Our researchers are playing a crucial role in investigating new methods to improve the well-being of people locally, nationally, and beyond, and are an excellent example of how Wayne State is empowering health in our neighborhoods, as well as fueling innovation with creative solutions to benefit the public.”

As PFAS regulation becomes more stringent, the findings from Wayne State University underscore the importance of considering both paternal and maternal health in mitigating the risks posed by environmental contaminants on future generations.