A groundbreaking study by UCLA Health has revealed that genes associated with DNA mismatch repair play a critical role in neuron damage in Huntington’s disease. Conducted in mouse models, the research highlights the potential for new therapeutic developments. The study was published in the journal Cell.

Understanding Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is one of the most common inherited neurodegenerative disorders. It progressively deteriorates movement control, motor skills, language, and cognitive functions, ultimately leading to death within 15 to 20 years of diagnosis. Despite extensive research, there is currently no cure or treatment that alters the course of the disease.

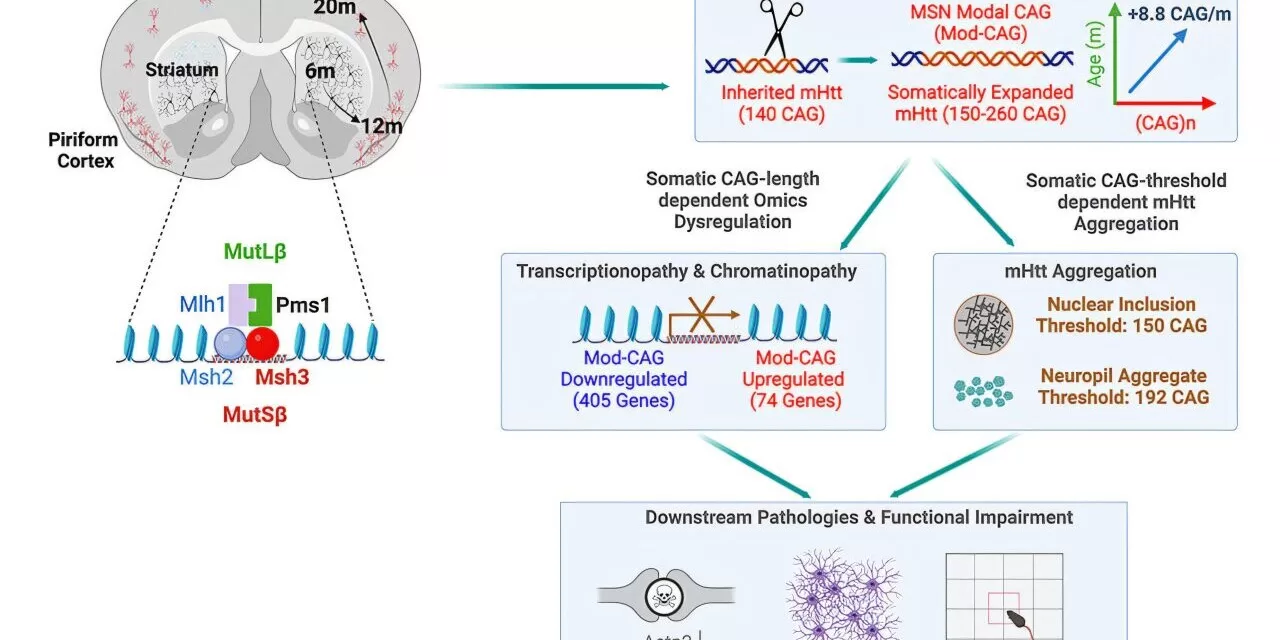

The root cause of Huntington’s disease was identified over three decades ago as a mutation involving excessive repeats of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) in the huntingtin gene. While individuals with 35 or fewer repeats remain unaffected, those with 40 or more CAG repeats will develop the disease, with earlier onset linked to higher repeat numbers. However, how this mutation leads to neurodegeneration remains largely unclear.

Genetic Mystery and Recent Breakthroughs

A key enigma in Huntington’s disease—and other neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s—is why only certain neurons are affected despite the mutated huntingtin protein being present throughout the body. Recent studies have identified DNA regions that contain “modifier” genes, which can influence disease onset. Many of these modifiers are involved in DNA mismatch repair, but their precise role in Huntington’s disease progression was unknown until now.

Key Findings of the UCLA Study

Led by Dr. X. William Yang, the study used Huntington’s disease mouse models to explore the impact of modifying nine patient-derived genes, including six mismatch repair genes. The researchers discovered that certain mismatch repair genes, particularly Msh3 and Pms1, drive disease progression by accelerating CAG repeat expansion in the most vulnerable neurons.

Remarkably, HD mice lacking Msh3 and Pms1 exhibited significant improvements, including:

- Correction of gene expression deficits

- Reduction or prevention of mutant huntingtin protein aggregates

- Improved motor function and neuronal health

- Long-term benefits lasting up to 20 months (comparable to 60 years in humans)

“Our study suggests that these genes are not just disease modifiers, as previously thought, but are genetic drivers of Huntington’s disease,” said Dr. Yang.

Implications for Therapy

The study provides crucial insights into potential treatments. Targeting Msh3 and Pms1 could slow disease progression and benefit multiple brain regions. Unlike other mismatch repair genes linked to cancer, these two are not known to have oncogenic properties, making them promising therapeutic targets. Additionally, the findings may extend beyond Huntington’s disease, offering potential avenues for treating other neurological disorders caused by dynamic DNA repeat mutations.

Future Directions

The research establishes a strong foundation for future therapeutic exploration, suggesting that reducing Msh3 and Pms1 activity could be a viable approach to slowing disease progression. Further studies will be needed to translate these findings into human treatments.

Disclaimer

This article is based on findings from a preclinical study in mice. While the results are promising, further research, including human clinical trials, is necessary to determine their applicability to patients with Huntington’s disease.