Read Time:7 Minute, 39 Second

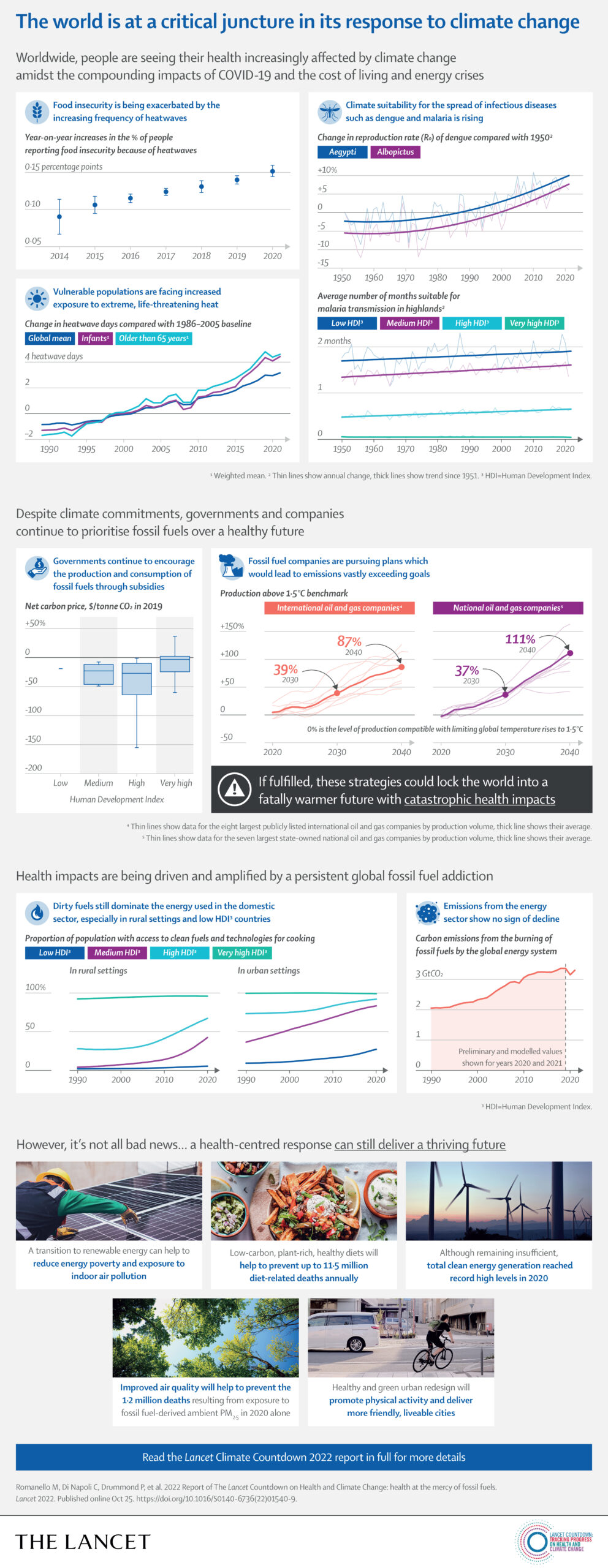

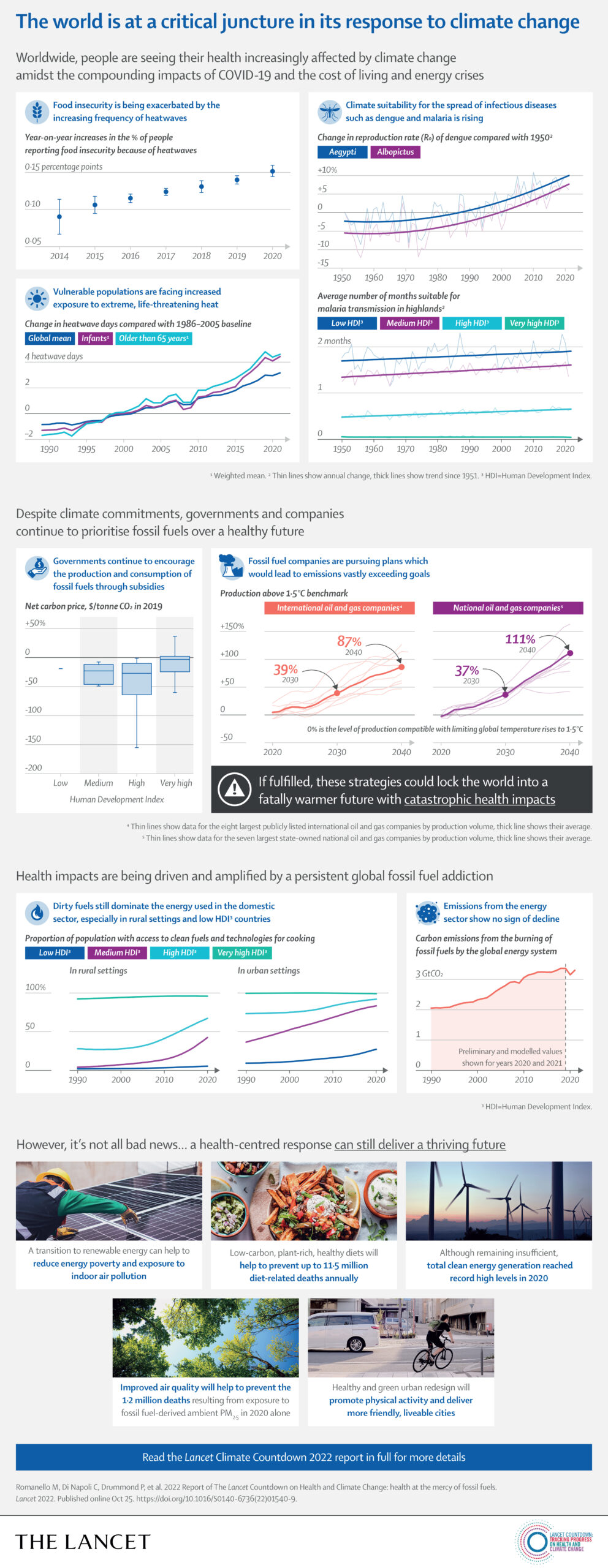

The world is at a critical juncture in its response to climate change. Worldwide, people are seeing their health increasingly affected by climate change amidst the compounding impacts of COVID-19 and the cost of living and energy crises; governments and companies continue to prioritise fossil fuels over a healthy future despite climate commitments; and rapid, holistic action is the only route to ensuring a just and healthy future.

Executive summary

The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown is published as the world confronts profound and concurrent systemic shocks. Countries and health systems continue to contend with the health, social, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a persistent fossil fuel overdependence has pushed the world into global energy and cost-of-living crises. As these crises unfold, climate change escalates unabated. Its worsening impacts are increasingly affecting the foundations of human health and wellbeing, exacerbating the vulnerability of the world’s populations to concurrent health threats.

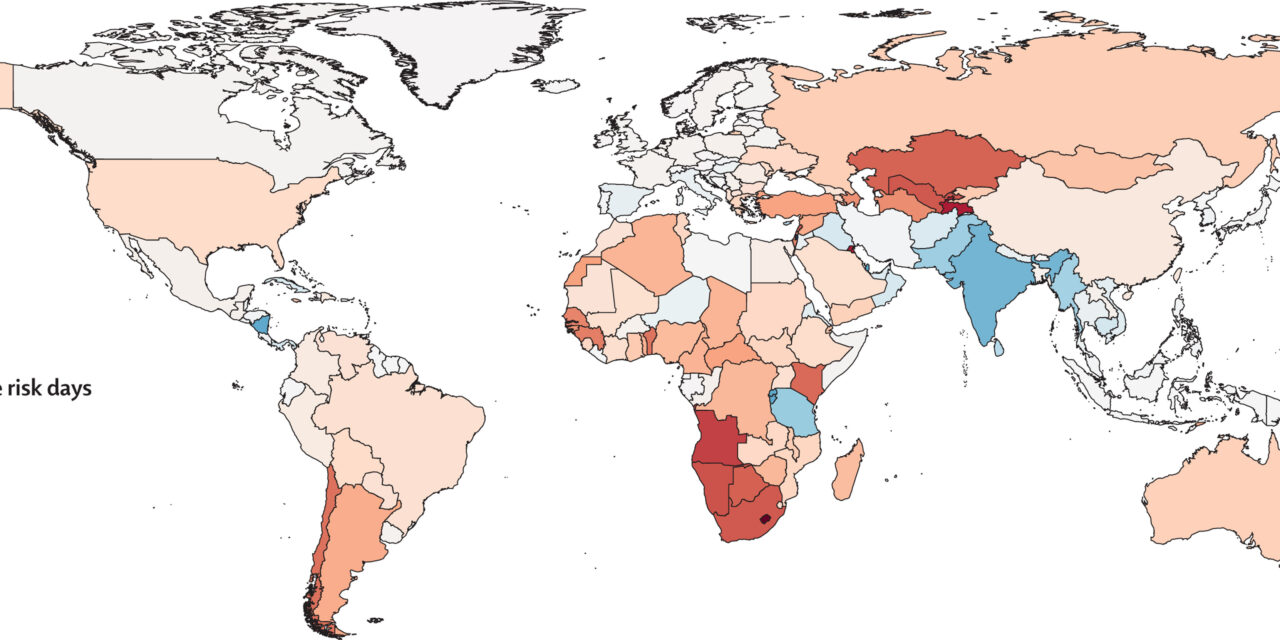

During 2021 and 2022, extreme weather events caused devastation across every continent, adding further pressure to health services already grappling with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Floods in Australia, Brazil, China, western Europe, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Africa, and South Sudan caused thousands of deaths, displaced hundreds of thousands of people, and caused billions of dollars in economic losses. Wildfires caused devastation in Canada, the USA, Greece, Algeria, Italy, Spain, and Türkiye, and record temperatures were recorded in many countries, including Australia, Canada, India, Italy, Oman, Türkiye, Pakistan, and the UK. With advancements in the science of detection and attribution studies, the influence of climate change over many events has now been quantified.

Because of the rapidly increasing temperatures, vulnerable populations (adults older than 65 years, and children younger than one year of age) were exposed to 3·7 billion more heatwave days in 2021 than annually in 1986–2005 (indicator 1.1.2), and heat-related deaths increased by 68% between 2000–04 and 2017–21 (indicator 1.1.5), a death toll that was significantly exacerbated by the confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Simultaneously, the changing climate is affecting the spread of infectious diseases, putting populations at higher risk of emerging diseases and co-epidemics. Coastal waters are becoming more suitable for the transmission of Vibrio pathogens; the number of months suitable for malaria transmission increased by 31·3% in the highland areas of the Americas and 13·8% in the highland areas of Africa from 1951–60 to 2012–21, and the likelihood of dengue transmission rose by 12% in the same period (indicator 1.3.1). The coexistence of dengue outbreaks with the COVID-19 pandemic led to aggravated pressure on health systems, misdiagnosis, and difficulties in the management of both diseases in many regions of South America, Asia, and Africa.

The economic losses associated with climate change impacts are also increasing pressure on families and economies already challenged with the synergistic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the international cost-of-living and energy crises, further undermining the socioeconomic determinants that good health depends on. Heat exposure led to 470 billion potential labour hours lost globally in 2021 (indicator 1.1.4), with potential income losses equivalent to 0·72% of the global economic output, increasing to 5·6% of the GDP in low Human Development Index (HDI) countries, where workers are most vulnerable to the effects of financial fluctuations (indicator 4.1.3). Meanwhile, extreme weather events caused damage worth US$253 billion in 2021, particularly burdening people in low HDI countries in which almost none of the losses were insured (indicator 4.1.1).

Through multiple and interconnected pathways, every dimension of food security is being affected by climate change, aggravating the impacts of other coexisting crises. The higher temperatures threaten crop yields directly, with the growth seasons of maize on average 9 days shorter in 2020, and the growth seasons of winter wheat and spring wheat 6 days shorter than for 1981–2010 globally (indicator 1.4). The threat to crop yields adds to the rising impact of extreme weather on supply chains, socioeconomic pressures, and the risk of infectious disease transmission, undermining food availability, access, stability, and utilisation. New analysis suggests that extreme heat was associated with 98 million more people reporting moderate to severe food insecurity in 2020 than annually in 1981–2010, in 103 countries analysed (indicator 1.4). The increasingly extreme weather worsens the stability of global food systems, acting in synergy with other concurrent crises to reverse progress towards hunger eradication. Indeed, the prevalence of undernourishment increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and up to 161 million more people faced hunger during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 than in 2019. This situation is now worsened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the energy and cost-of-living crises, with impacts on international agricultural production and supply chains threatening to result in 13 million additional people facing undernutrition in 2022.

Conclusion: the 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown

In its seventh iteration, the 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown shows the direst findings yet. At 1·1°C of heating,

climate change is increasingly undermining every pillar of good health and compounding the health impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflicts. The health harms of extreme heat exposure are rising, affecting mental health, undermining the capacity to work and exercise, and resulting in annual heat-related deaths in people older than 65 years increasing by 68% from 2000–04 to 2017–21 (indicators 1.1.1–1.1.5). more frequent and extreme weather events are increasingly affecting physical and mental health directly and indirectly, with economic losses particularly over-burdening low HDI countries, in which losses are mostly uninsured (indicators 1.2.1–1.2.3 and 4.1.1). The changing climate is exacerbating the risk of infectious disease outbreaks (indicator 1.3) and threatening global food security, with heatwave days associated with 98 million more people experiencing food insecurity in 2020 than in 1981–2010 (indicator 1.4).

These health impacts add additional pressure on overwhelmed health systems. With a further 0·4°C temperature rise probably unavoidable, accelerated adaptation is more urgent than ever. Yet, national and city authorities are not acting fast enough and adaptation funding remains grossly insufficient (indicators 2.1.1, 2.1.2, and 2.2.4). The increased use of air conditioning and scant implementation of nature-based solutions (indicators 2.2.2–2.2.3) reflects a drift towards unplanned, maladaptive responses. Concerningly, and at least partly caused by wealthier countries’ failure to meet climate their finance commitments , the adaptation response is often slower in low HDI countries, increasing their vulnerability to a climate crisis that they have had little, if any, contribution too.

Despite these profound health impacts, mitigation efforts remain inadequate to avert a catastrophic temperature rise.

CO2 emissions from fuel combustion increased by 6% in 2021 (indicator 3.1) and agricultural greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 31% since 2000 (indicator 3.5.1). The inaction came with major health costs: fossil fuels contributed to 1·3 million deaths from ambient PM2·5 exposure in 2020; the over-dependence on solid fuels, worsened by the energy crisis, increased exposure to indoor air pollution (indicators 3.3 and 3.2);and consumption of carbon-intensive meat and dairy resulted in 2 million deaths in 2019. Meanwhile, governments provide billions of dollars annually for fossil fuel subsidies (indicator 4.2.4).

However, some indicators provide a glimmer of hope. Government engagement with health and climate change reached record levels in 2021, and the updated NDCs reflect increased awareness of the need to protect health from climate change hazards (indicator 5.4). Renewable electricity generation and electric vehicle use reached record growth, and investments and employment in the clean energy industry are slowly increasing (indicators 3.1, 3.4, 4.2.1, and 4.2.2). If sustained, these shifts could provide energy security, better jobs, cleaner air, and a path for a green COVID-19 recovery. Meanwhile, the health sector is increasingly preparing to face climate hazards (indicator 2.2.1), with 60 countries committing to developing climate-resilient and/or low-carbon or net zero-carbon health systems at COP26.

An expanding number of countries are starting to develop their own observatories, to monitor and identify progress on health and climate change. However, this could come too little too late.

With countries facing multiple crises simultaneously, their policies on COVID-19 recovery and energy sovereignty will have profound, and potentially irreversible consequences for health and climate change. However, accelerated climate action would deliver cascading benefits, with more resilient health, food, and energy systems, and improved security and diplomatic autonomy, minimising the health impact of health shocks. With the world in turmoil, putting human health at the centre of an aligned response to these concurrent crises could represent the last hope of securing a healthier, safer future for all.

Explore the key findings from the 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change below, or read the full paper for more detail.

Sources: Lancet

Happy

0

0 %

Sad

0

0 %

Excited

0

0 %

Sleepy

0

0 %

Angry

0

0 %

Surprise

0

0 %