Cambridge, MA — Low-calorie diets and intermittent fasting have garnered attention for their promising health benefits, including delaying the onset of age-related diseases and extending lifespan across various organisms. Recent research from MIT, however, highlights a more complex picture, revealing both the regenerative advantages and potential risks associated with fasting.

Boosting Regeneration: The Positive Side

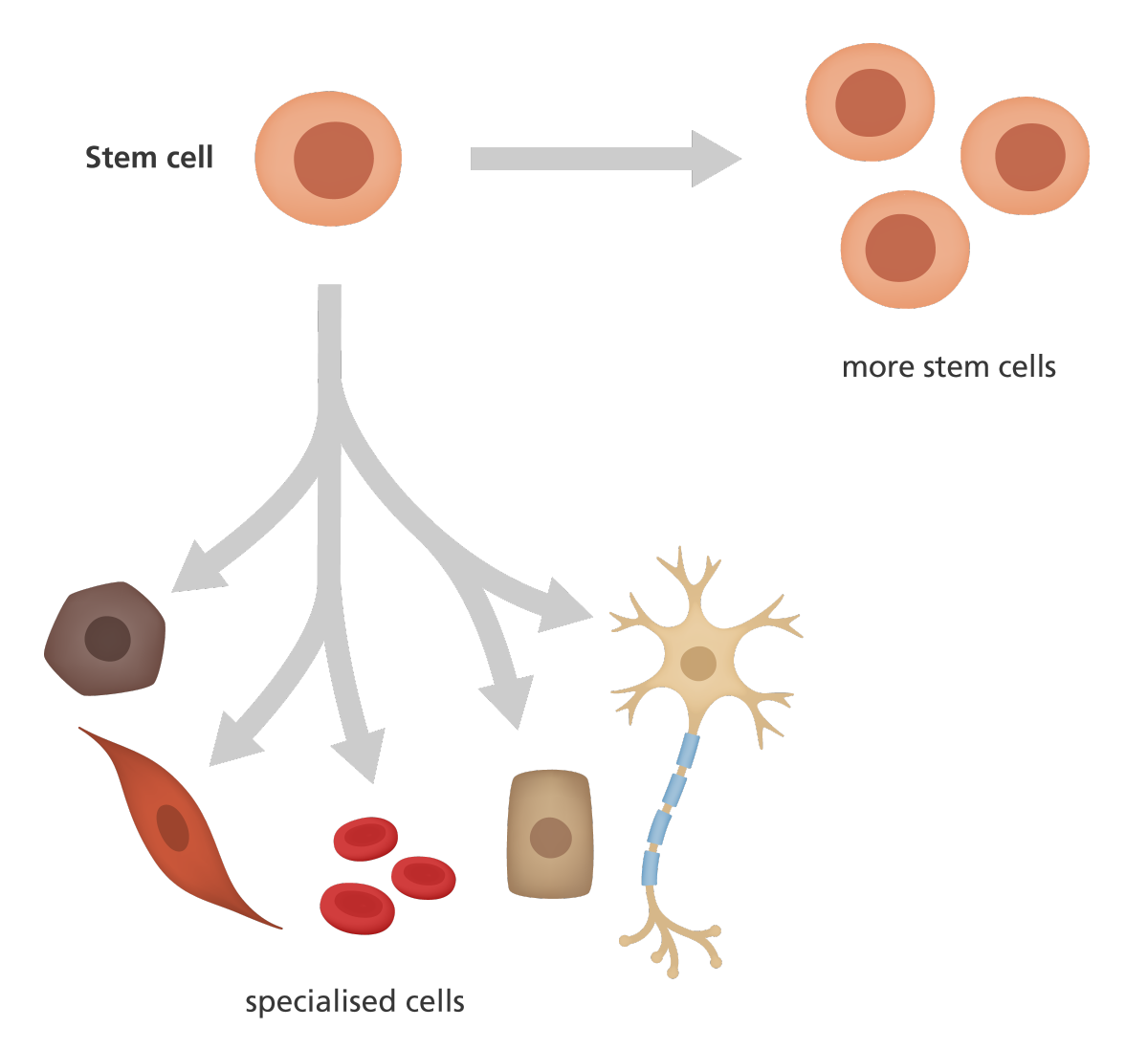

In a new study published in Nature, MIT researchers have provided deeper insights into how fasting influences intestinal health. Building on previous work, the team led by Dr. Omer Yilmaz discovered that fasting enhances the regenerative abilities of intestinal stem cells, which play a crucial role in repairing intestinal damage and inflammation. Their findings demonstrate that during the refeeding period following a fast, stem cells experience a significant surge in proliferation, largely driven by a cellular signaling pathway known as mTOR.

“Fasting and refeeding represent two distinct states,” explains Shinya Imada, a postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the study. “Fasting induces a state where cells rely on lipids for energy, allowing them to survive nutrient deprivation. Once refeeding begins, these cells activate programs that promote rapid regeneration and repair of the intestinal lining.”

The activation of mTOR during refeeding facilitates increased protein synthesis, necessary for building new cellular mass and replenishing the intestinal lining. This process involves the production of polyamines, molecules essential for cell growth and division.

The Downsides: Increased Cancer Risk

Despite these regenerative benefits, the study also uncovers a potential downside. The same period of heightened stem cell activity that promotes healing may also increase the risk of cancerous developments. In their experiments with mice, researchers observed that cancerous mutations occurring during the refeeding phase were more likely to lead to early-stage intestinal tumors compared to mutations occurring during fasting.

“Having more stem cell activity is good for regeneration, but too much of a good thing over time can have less favorable consequences,” warns Dr. Yilmaz. The researchers noted that mice with induced cancer mutations during the refeeding stage developed precancerous polyps more frequently than those with mutations occurring during fasting.

This raises important considerations for human health. “We still have a lot to learn,” Yilmaz notes, “but this research suggests that while fasting may offer significant health benefits, the subsequent refeeding phase could potentially increase cancer risks if mutagenic exposures occur.”

Future Directions

The team is exploring whether similar mechanisms occur in humans and investigating whether interventions like polyamine supplements could stimulate regeneration without the need for fasting. This research could have implications for individuals undergoing treatments that damage the intestinal lining, such as radiation therapy.

The study, funded by prestigious institutions including the Pew-Stewart Trust Scholar award and the Koch Institute-Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Bridge Project, underscores the need for further research to fully understand the balance between the regenerative and potentially risky effects of fasting.

As scientists continue to unravel these complex interactions, individuals considering fasting should remain informed about both its potential benefits and risks, and seek personalized advice from healthcare professionals.