In a revealing study published on the preprint server bioRxiv, Paul Jensen, a microbial-systems biologist at the University of Michigan, discovered a shocking imbalance in the study of bacteria. While artificial intelligence (AI) tools like large language models are helping to synthesize research across scientific fields, microbiologists may be struggling with an overwhelming lack of data on many bacterial species. The study highlighted that a vast majority of bacteria, particularly those crucial for human and environmental health, remain largely ignored in the scientific literature.

Jensen, who specializes in Streptococcus sobrinus, a bacterium linked to tooth decay, set out to explore the extent of existing research using AI. However, after reviewing the literature, he found only a handful of papers on S. sobrinus, many of which he had already read. Jensen expanded his search to encompass 43,409 unique bacterial species, analyzing the number of publications indexed in PubMed, a comprehensive biomedical literature repository.

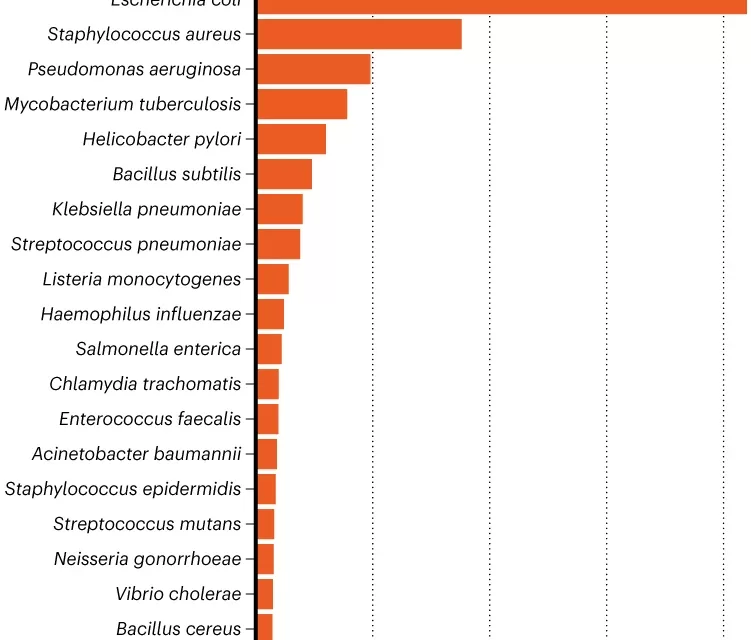

The findings were stark: just ten bacterial species, such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, accounted for half of all microbiology research publications. E. coli alone dominated with over 312,000 papers, making up 21% of the total. Meanwhile, nearly 75% of the bacterial species included in the study had no publications devoted to them, underscoring a glaring gap in research focus.

This trend is especially troubling when considering the bacteria that impact human health and the planet’s ecosystems. Many microbes critical to the human microbiome, as well as those that inhabit diverse environments such as oceans and soil, have been almost entirely overlooked. “We’ve learned a lot about a small number of species,” Jensen remarked. “But for a lot of bacteria, there’s nothing for a language model, for an AI to read.”

Jensen’s research also suggests that the disparity between well-studied bacteria and those that remain understudied has only grown over the past 25 years. This widening gap is partly attributed to the rise of microbiome studies, which involve sequencing microbes en masse, but have still largely neglected the broader microbial diversity found in nature.

Prominent microbiome scientists, such as Nicola Segata from the University of Trento, have expressed concern over these findings. Segata pointed out that many microbes that are abundant in healthy human microbiomes are absent from the list of most-studied species, and some haven’t even been formally named. “These species still have a long way before they will be studied at the level they deserve,” he said.

Brett Baker, a microbial ecologist at the University of Texas, emphasized the underrepresentation of microbes in ecosystems beyond the human body. “None of the dominant organisms in nature are on this list. That’s a problem,” he said, calling for more comprehensive studies to understand the crucial microbes that contribute to Earth’s biodiversity.

Jensen’s research serves as a call to action for the scientific community to broaden its focus beyond a small set of model organisms and prioritize the study of the vast majority of bacterial species that remain largely unexplored. As the field of microbiology grows, it is essential to recognize that the unseen and understudied organisms could hold the key to understanding both human health and the complex ecosystems we depend on.

References

Jensen, P. A. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.04.631297 (2025).