A study presented at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference 2025, held in Los Angeles, has found that a common bacteria found in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract, Streptococcus anginosus, could be linked to a higher risk of stroke and worse prognosis in stroke survivors. This research, led by Dr. Shuichi Tonomura from the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Osaka, Japan, offers new insights into the connection between oral bacteria and stroke risk.

Dr. Tonomura explained that if a quick test could detect harmful bacteria in the mouth and gut, it might be possible to assess stroke risk and prevent future strokes. “Targeting these specific harmful oral bacteria may help prevent stroke,” he said.

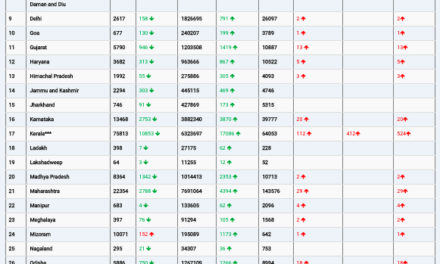

The study, conducted at Japan’s largest stroke center, analyzed bacteria in the saliva and gut of people who had recently suffered a stroke. The researchers found that Streptococcus anginosus was significantly more abundant in the gut and saliva of stroke patients compared to a control group of individuals without a stroke. Furthermore, this bacteria was associated with a 20% increased likelihood of stroke, independent of traditional vascular risk factors like high blood pressure and diabetes.

Over a two-year follow-up period, stroke survivors with higher levels of S. anginosus in their gut were found to have a significantly higher risk of death and major cardiovascular events. Conversely, two other types of gut bacteria—Anaerostipes hadrus and Bacteroides plebeius—were associated with a reduced stroke risk, suggesting potential protective effects.

Dr. Tonomura emphasized the importance of oral hygiene in reducing harmful bacteria that contribute to conditions like tooth decay. “Maintaining good oral hygiene is essential, as these bacteria produce acids that break down tooth enamel,” he said. This highlights the role of reducing sugar intake and using toothpaste that targets harmful bacteria in preventing both tooth decay and stroke risk.

The study’s authors hope to expand their research to include people who have not yet had a stroke but have risk factors for the condition. Dr. Tonomura emphasized that broader studies, especially those looking at populations at risk, are crucial to understanding the full implications of the findings.

However, there are limitations to the study. The research, conducted on a relatively small sample of 189 stroke patients and 55 control participants, was specific to a Japanese population. Dr. Tonomura noted that other bacteria may play a more significant role in stroke risk in different countries, where lifestyles and diets vary.

In response to the findings, Dr. Louise D. McCullough, a neurologist at McGovern Medical School in Houston, pointed out that further studies in larger, diverse populations would be necessary to validate these results and help develop targeted prevention strategies.

Disclaimer: This study is preliminary, and while promising, its findings require further investigation and replication in larger, more diverse populations to fully understand the role of oral and gut microbiota in stroke risk. The research does not yet provide conclusive evidence for clinical use.