A recent collaborative study conducted by researchers from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, the Columbia Aging Center, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health has shed light on a crucial aspect of maintaining cognitive health in old age. The study, published in Neurology, suggests that individuals who engage in mentally challenging jobs during their midlife years are less likely to develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia after the age of 70.

Led by Vegard Skirbekk, PhD, professor of Epidemiology at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, and Trine Holt Edwin from Oslo University Hospital, the study offers a significant advancement in understanding the association between cognitive stimulation in midlife and cognitive health in later years. Unlike previous research relying on subjective evaluations, this study employed objective assessments to establish this link.

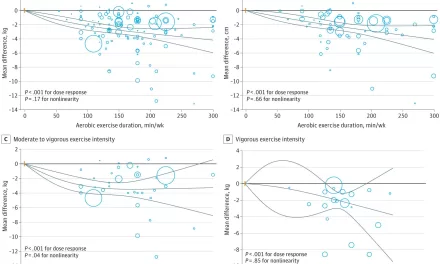

The researchers analyzed data from the Norwegian administrative registry, combined with occupational attributes from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) database, encompassing more than 300 different jobs. They computed a Routine Task Intensity (RTI) index to measure occupational cognitive demands, with lower RTI scores indicating more cognitively demanding occupations.

Group-based trajectory modeling identified four distinct groups based on the level of cognitive demands in participants’ occupations during their 30s to 60s. Subsequently, the researchers examined the association between these trajectory groups and the development of MCI and dementia in participants aged 70 and above.

Adjusting for various dementia risk factors such as age, gender, education, income, overall health, and lifestyle habits, the study found compelling evidence. Individuals with low occupational cognitive demands (high RTI) had a 37 percent higher risk of dementia compared to those with high occupational cognitive demands.

Trine Holt Edwin emphasizes the importance of both education and cognitively stimulating work environments for preserving cognitive health in older age. However, she notes that while education influences this association, occupational complexity also plays a significant role.

Yaakov Stern, Principal Investigator of the project at Columbia University, underscores the study’s contributions. Utilizing registry data on occupational histories strengthens the evidence and advances the understanding of how occupational cognitive demands impact cognitive health later in life.

In conclusion, Vegard Skirbekk highlights the study’s overarching message: high occupational cognitive demands correlate with lower risks of MCI and dementia in later life. He suggests further research to pinpoint specific occupational cognitive demands that are most advantageous for maintaining cognitive health in old age.

It’s crucial to note that while this study identifies associations, it does not establish direct causation. Additionally, the study did not differentiate between varying cognitive requirements within the same occupational category or consider changes in job responsibilities over time.

The study was made possible through the collaboration of various institutions including the HUNT Research Centre, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and the Cognitive Neuroscience Division, Department of Neurology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.