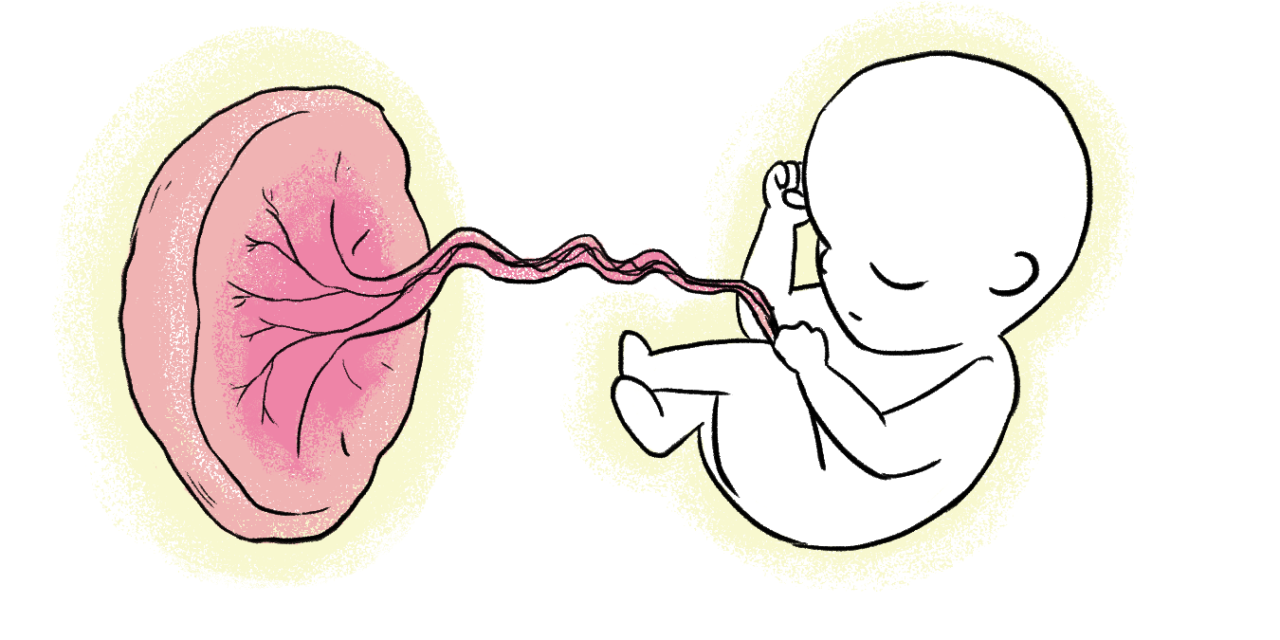

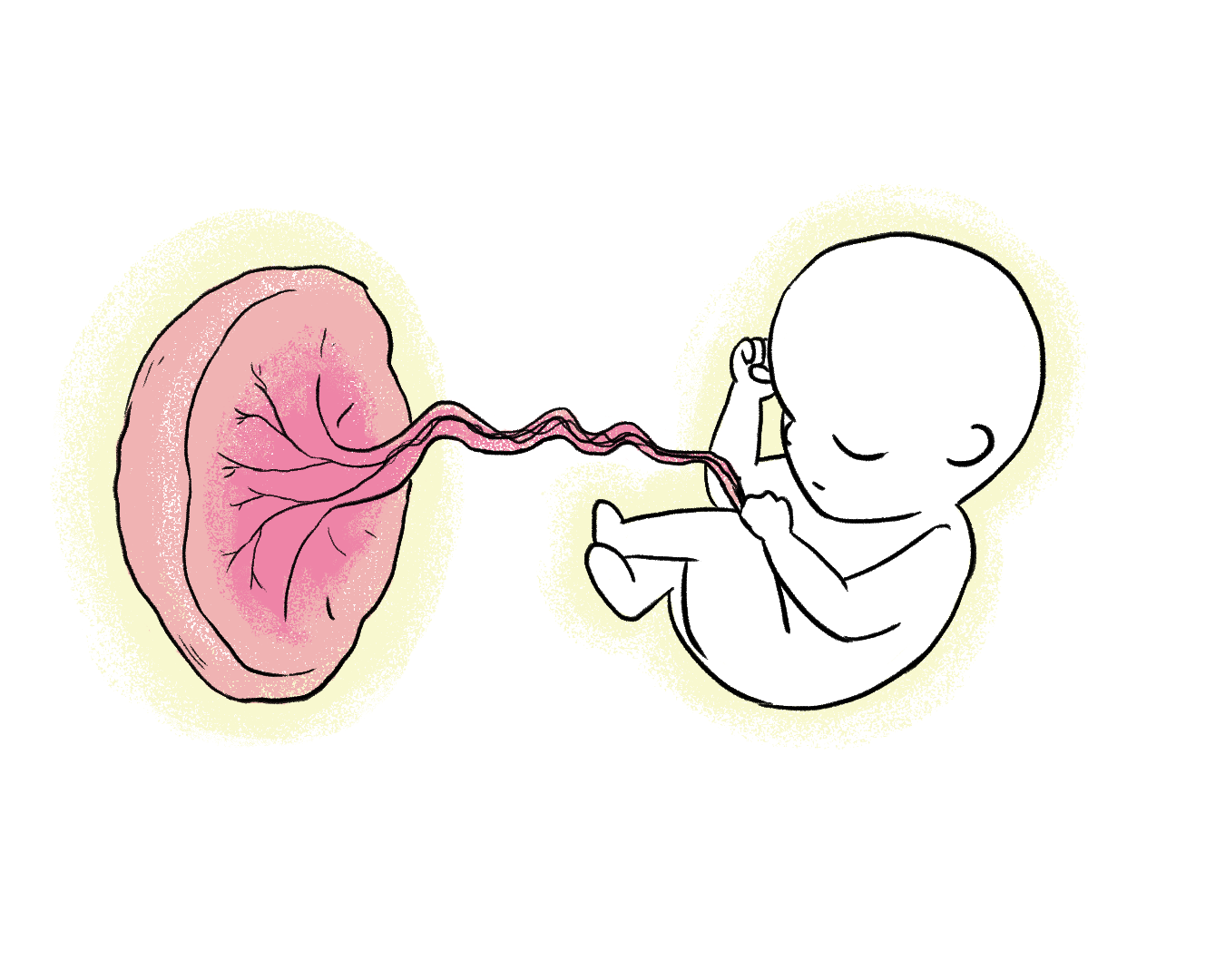

Researchers have made a breakthrough in understanding unexplained pregnancy losses by utilizing placental testing. Their study demonstrated that this approach accurately identified the underlying pathology in over 90 percent of previously perplexing cases, potentially paving the way for improved prenatal treatments. Published in the journal Reproductive Sciences, this research addresses a significant issue, as around 5 million pregnancies end in miscarriage in the United States, with over 20,000 resulting in stillbirths after 20 weeks of gestation. Alarmingly, up to half of these losses fall under the “unspecified” category.

Dr. Harvey Kliman, the senior author and a research scientist at Yale School of Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology, and Reproductive Sciences, expressed the common experience of patients receiving an unexplained loss and being advised to try again, which can intensify their sense of culpability for the outcome. Kliman, who also heads the Reproductive and Placental Research Unit, emphasized the emotional burden on affected families, stating, “To have a pregnancy loss is a tragedy. To be told there is no explanation adds tremendous pain for these lost families.”

The objective of the study was to enhance existing classification systems in order to reduce the number of cases remaining unspecified. Collaborating with Beatrix Thompson, a current medical student at Harvard University, and Parker Holzer, a former graduate student in Yale’s Department of Statistics and Data Science, Kliman developed an expanded classification system based on pathological examination of loss placentas.

The team began with a dataset of 1,527 pregnancies that resulted in loss and were referred to Kliman’s consult service at Yale for evaluation. After excluding cases lacking sufficient material for examination, they examined 1,256 placentas from 922 patients. They introduced additional categories, namely “placenta with abnormal development” (dysmorphic placentas) and “small placenta” (a placenta below the 10th percentile for gestational age), complementing the existing classifications of cord accidents, abruptions, thrombotic events, and infections.

Kliman emphasized the potential impact of this work, indicating that over 7,000 small placentas associated with stillbirths each year could potentially be detected in utero, enabling proactive measures before a loss occurs. Additionally, the identification of dysmorphic placentas may offer a means to detect genetic abnormalities in the nearly 1 million miscarriages that occur annually in the United States.

He further noted, “Having a concrete explanation for a pregnancy loss helps the family understand that their loss was not their fault, allows them to start the healing process, and, when possible, prevent similar losses — especially stillbirths — from occurring in the future.”