In a groundbreaking discovery, an international team of researchers has identified cases of chromosomal disorders, shedding light on ancient populations’ understanding and treatment of individuals with such conditions. Among the findings is what could potentially be the earliest-known case of Edwards syndrome from prehistoric remains, alongside six instances of Down syndrome.

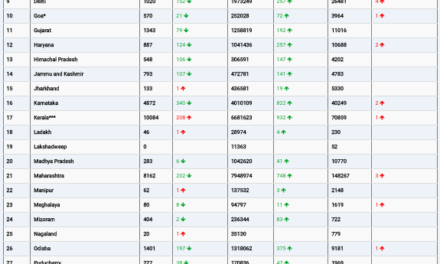

The research, led by Dr. Adam “Ben” Rohrlach of the University of Adelaide and Dr. Kay Prüfer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, analyzed ancient DNA from human populations spanning various regions, including Spain, Bulgaria, Finland, and Greece, dating back as far as 4,500 years.

Dr. Rohrlach, a statistician from the University of Adelaide’s School of Mathematical Sciences, explained, “Using a new statistical model, we screened the DNA extracted from human remains from different historical periods. We identified six cases of Down syndrome, marking the first time such cases have been reliably detected in ancient remains.”

Down syndrome, characterized by an extra copy of chromosome 21, was identified through a novel Bayesian approach, which efficiently screened tens of thousands of ancient DNA samples. Dr. Patxuka de-Miguel-Ibáñez of the University of Alicante, lead osteologist for the Spanish sites, highlighted the significance of comparing remains for common skeletal abnormalities associated with Down syndrome when DNA analysis alone is inconclusive.

Moreover, the study uncovered a singular case of Edwards syndrome, a rare condition resulting from three copies of chromosome 18. This finding presented severe skeletal abnormalities, suggesting a gestational age of approximately 40 weeks.

Remarkably, all detected cases were found in perinatal or infant burials, underscoring the care and societal recognition afforded to individuals with these conditions. Professor Roberto Risch, archaeologist from The Autonomous University of Barcelona, noted the significance of detecting the sole case of Edwards syndrome and the increase in Down syndrome cases, particularly during the Early Iron Age in Spain. He speculated on the purposeful selection of these infants for special burials within settlements or significant structures.

The study’s findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, offer invaluable insights into ancient communities’ attitudes toward and treatment of individuals with chromosomal disorders. The collaborative effort, involving researchers from the University of Adelaide and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, among others, signifies a significant stride in understanding ancient human populations’ health and social dynamics.