In a recent study, it has been found that close familial unions, also known as consanguinity, may elevate the risk of developing common conditions such as type 2 diabetes and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

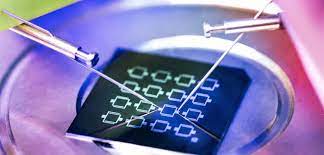

To investigate the connection between autozygosity (a measure of genetic relatedness between a person’s parents) and the prevalence of widespread diseases, scientists from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, in collaboration with Queen Mary University of London, employed a novel approach that reduces potential bias from socio-cultural factors. The study focused on the Genes & Health cohort, which encompasses individuals of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage, along with those with European and South Asian ancestry from the UK Biobank.

To ensure accessibility to the general public, the Genes & Health Community Advisory Board collaborated with the researchers to produce a document outlining the study’s goals, methodology, and findings.

Published in Cell on September 26th, the findings shed light on the intricate relationship between genetics and health outcomes, particularly in populations with higher rates of consanguinity.

Consanguinity involves the practice of marriage between individuals who share a recent common ancestor, such as a grandparent or great-grandparent. This practice is observed worldwide, with varying frequencies. Over 10 percent of the global population comprises individuals who are offspring of second cousins or closer. In the UK, consanguinity is more prevalent among certain British South Asian communities.

Consanguinity increases the portion of an individual’s genetic makeup inherited identically from both parents, a phenomenon known as autozygosity. While it’s established that consanguinity heightens the risk of rare single-gene disorders, its impact on common diseases has been less explored.

British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis exhibit higher rates of several diseases compared to the UK average, such as a four-to-six-fold increased risk of type 2 diabetes in comparison to individuals of European ancestry. However, these diseases result from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, and prior to this study, it was unclear whether consanguinity played a role.

In this new study, researchers delved into the influence of consanguinity on complex genetic diseases. They analyzed genomic data from distinct populations, including almost 24,000 British individuals of Pakistani and Bangladeshi descent from the Genes & Health cohort, as well as over 397,000 individuals of European or South Asian descent from the UK Biobank cohort. They found that around 33% of individuals in Genes & Health were offspring of second cousins or closer, as opposed to 2% of individuals of European descent in UK Biobank.

The researchers then explored the connection between autozygosity and the prevalence of common diseases, focusing on a subset of around 5700 individuals with parents inferred to be first cousins. Within this ‘highly consanguineous’ group, autozygosity levels ranged from 4 to 15 percent. The researchers demonstrated that these levels were not correlated with socio-cultural or environmental factors, ensuring that any observed links between autozygosity and diseases were biologically rooted.

Out of the 61 complex genetic diseases examined, the researchers identified 12 diseases and disorders associated with increased autozygosity resulting from consanguinity. These included type 2 diabetes, asthma, and PTSD. The associations with type 2 diabetes and PTSD were further validated in a separate dataset from the genetic company 23andMe Inc., using a between-sibling analysis technique.

The analysis suggests that consanguinity may account for approximately 10 percent of type 2 diabetes cases among British Pakistanis and around 3 percent among British Bangladeshis. However, any health risks associated with consanguinity should be weighed against its positive social benefits, and considered alongside other more substantial modifiable risk factors like exercise, smoking, and body mass index.

This research offers valuable insights into the factors influencing health outcomes and the connections between autozygosity and complex diseases within British Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities. It suggests that genetic studies of complex diseases should broaden their focus to pinpoint specific variants and genes with recessive effects.

Daniel Malawsky, the study’s first author and a PhD student at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, remarked, “While consanguinity has a smaller role in common diseases compared to other factors, it is still essential to understand its specific influence on health in these communities. Our new method exploring the natural variation in expected autozygosity amongst offspring of first cousins was a key breakthrough in helping us to test its impact. Some of our results suggested that cultural and environmental factors associated with consanguinity can sometimes exaggerate associations between autozygosity and health-related traits, or even mask truly causal associations. Our results suggest that some findings from previous studies linking autozygosity to complex traits in humans may have been misleading.”

Cllr Ahsan Khan, chair of the Genes & Health community advisory board and councillor at Waltham Forest, emphasized the importance of culturally sensitive approaches in health research, recognizing the delicate balance between social benefits and potential risks. Khan also praised the active engagement of community members in the research process.

Prof Sarah Finer, author of the study and co-lead of the Genes & Health research programme from Queen Mary, University of London, acknowledged the invaluable contribution of the thousands of volunteers who participated in the Genes & Health study and UK Biobank.

Dr Hilary Martin, senior author of the paper and group leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, highlighted the potential impact of the findings on disease risk prediction and future research efforts to identify specific genetic variants associated with these diseases. This knowledge could aid in earlier screening and the identification of potential drug targets, not only in these specific communities but also globally, especially in populations where consanguinity rates are higher.