February 6, 2025 – Columbia University researchers have uncovered specialized neurons in the brainstem of mice that play a key role in telling the body when to stop eating. These neurons, described in the paper “Brainstem Neuropeptidergic Neurons Link a Neurohumoral Axis to Satiation,” published on February 5 in the journal Cell, could pave the way for new treatments targeting obesity.

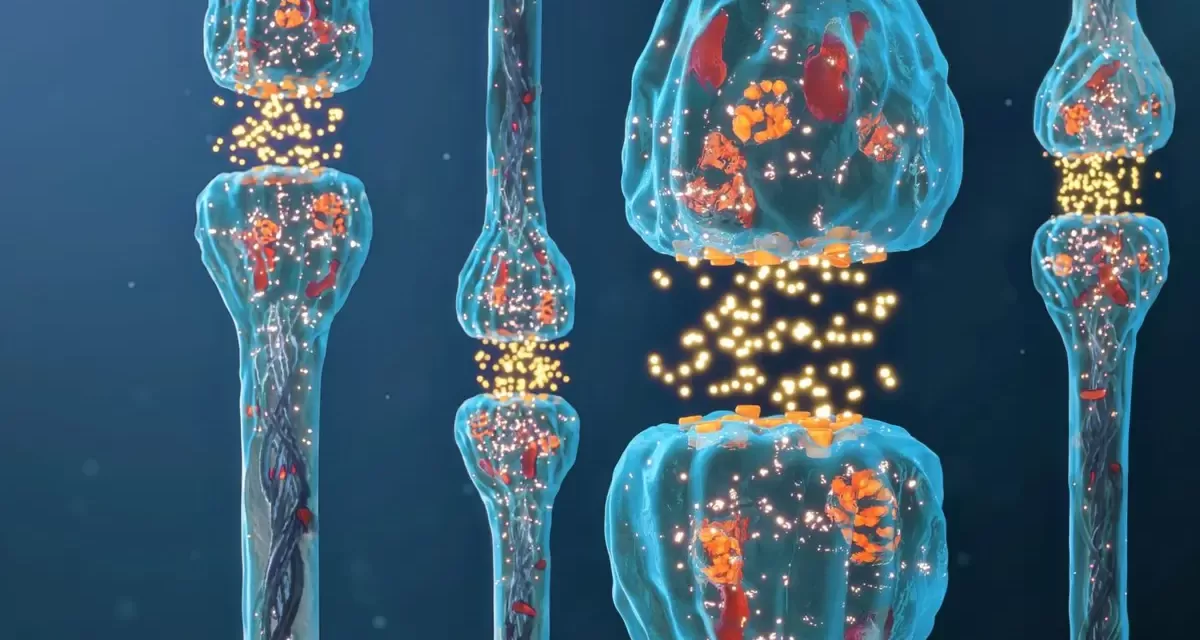

While previous studies have identified various brain circuits that help monitor food intake, these newly discovered neurons are unique in that they make the ultimate decision to halt eating. Situated in the brainstem—the most ancient part of the vertebrate brain—these cells integrate a range of signals, including sensory information from food and hormonal responses, to regulate satiety.

Dr. Alexander Nectow, the lead researcher and physician-scientist at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, explained, “These neurons are unlike others involved in regulating satiation. They bring together different pieces of information, such as how food tastes, how it fills the stomach, and the hormones released in response to eating.”

The sensation of fullness—a universal experience at the dinner table—happens when the brain receives signals indicating that enough food has been consumed. But how exactly does the brain know when to stop? Nectow and his colleague Srikanta Chowdhury, an associate research scientist, aimed to answer this by exploring the brainstem region responsible for processing complex signals.

Through innovative single-cell techniques, including spatially resolved molecular profiling, the researchers were able to identify previously unrecognized neurons. These cells, unlike other known appetite-regulating neurons, seemed to track the food intake process, responding to visual, sensory, and hormonal cues associated with eating.

To investigate how these neurons impact eating behavior, the scientists engineered them to be activated and deactivated using light. When the neurons were activated, the mice ate significantly smaller meals, and the rate of eating slowed gradually—indicating that these neurons do not just signal an immediate stop but help modulate the process of satiety.

The study also examined how hormones influence the neurons. Researchers discovered that appetite-stimulating hormones could silence the neurons, while GLP-1 agonists—a class of drugs used to treat obesity and diabetes—activated them. This confirmed that the neurons help to track each bite of food, allowing the brain to sense when enough has been eaten.

Though these neurons were identified in mice, their location in the brainstem suggests that humans likely possess similar cells. Dr. Nectow believes the discovery could offer crucial insights into how fullness is perceived and utilized to end meals. Furthermore, the findings may lead to novel therapies for obesity, a condition that affects millions worldwide.

As researchers continue to explore this promising discovery, the team hopes it could one day be applied to develop more effective treatments for obesity, a disease that remains challenging to manage.

Disclaimer: This article is based on the findings of the study “Brainstem Neuropeptidergic Neurons Link a Neurohumoral Axis to Satiation,” published in Cell on February 5, 2025. Further research is needed to confirm the application of these findings to human physiology and potential therapies.