Resistant starch, a type of non-digestible fiber that undergoes fermentation in the large intestine, has shown promise in improving metabolism based on previous animal studies. In a four-month randomized controlled trial involving individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), it was discovered that regular consumption of resistant starch led to alterations in gut flora composition, resulting in lower levels of liver triglycerides and enzymes associated with liver inflammation and injury. These findings were published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

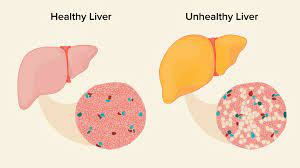

NAFLD, characterized by an accumulation of fat in the liver, affects approximately 30 percent of the global population. It can lead to severe liver damage and exacerbate conditions like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Currently, there is no approved pharmaceutical treatment for NAFLD, with doctors typically recommending dietary modifications and exercise.

Huating Li, the co-corresponding author at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, emphasized the significance of finding an effective approach for managing NAFLD through potentially identifying new therapeutic targets.

Previous studies have suggested a link between NAFLD and disruptions in gut microbiota. Even in the early stages of NAFLD, individuals exhibit an altered gut bacteria profile. This prompted Li and her team to investigate whether resistant starch, known to promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, could be a viable treatment for NAFLD.

The study enrolled 200 NAFLD patients, providing them with a balanced dietary plan crafted by a nutritionist. Among them, 100 patients received a resistant starch powder derived from maize, while the other 100 received a calorie-matched non-resistant corn starch as a control. They were instructed to consume 20 grams of the starch mixed with 300 mL of water (1 ¼ cups) before meals twice a day for four months.

At the conclusion of the four-month trial, participants who received the resistant starch treatment exhibited nearly a 40 percent reduction in liver triglyceride levels compared to the control group. Additionally, those who underwent the resistant starch treatment experienced decreases in liver enzymes and inflammatory factors associated with NAFLD. Importantly, these benefits were still evident even after accounting for weight loss.

Yueqiong Ni, the co-first author at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital and Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans-Knöll-Institute (HKI) in Germany, noted that the study demonstrated that resistant starch’s impact on improving liver conditions is independent of changes in body weight.

Through an analysis of patients’ fecal samples, the team observed that the resistant starch group exhibited a distinct microbiota composition and functionality compared to the control. Notably, the treatment-group patients displayed a lower level of Bacteroides stercoris, a crucial bacterial species affecting fat metabolism in the liver through its metabolites. The reduction in B. stercoris was strongly correlated with the decrease in liver triglyceride content, liver enzymes, and metabolites.

When the team transplanted fecal microbiota from resistant starch-treated patients to mice fed a high-fat high-cholesterol diet, the mice demonstrated a significant reduction in liver weight and triglyceride levels, along with improved liver tissue grading, in comparison to mice that received microbiota from the control group.

Li emphasized the study’s identification of a new intervention for NAFLD, one that is effective, affordable, and sustainable. Adding resistant starch to a normal and balanced diet is much more manageable for individuals compared to strenuous exercise or weight loss treatments.