A recent study has revealed that prolonged exposure to arsenic in drinking water, even at levels below regulatory limits, may significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), particularly ischemic heart disease. This groundbreaking research, led by Columbia University scientists and published in Environmental Health Perspectives, is the first to establish a clear link between lower-than-regulated arsenic concentrations and heart disease risk.

The study is a major step in broadening our understanding of the health effects of long-term arsenic exposure, a common issue in areas reliant on contaminated groundwater. “Our findings further reinforce the importance of considering non-cancer outcomes, and specifically cardiovascular disease, which is the number one cause of death in the US and globally,” said Danielle Medgyesi, a doctoral student at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health.

Key Findings

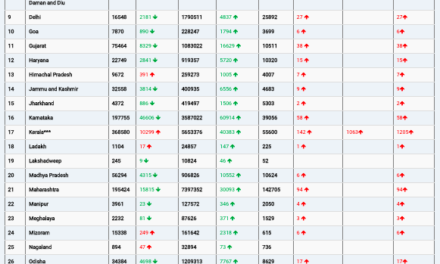

The researchers analyzed data from 98,250 participants, including 6,119 cases of ischemic heart disease and 9,936 cases of broader cardiovascular diseases. They focused on community water supplies (CWS) as a source of long-term arsenic exposure and examined how this exposure affected cardiovascular health over time. The results were striking: individuals exposed to arsenic concentrations between 5 to 10 micrograms per liter — still below the regulatory limit of 10 micrograms per liter — faced a 20% increased risk of heart disease. Approximately 3.2% of participants were affected by these levels of exposure.

The study found that the most dangerous period of exposure was the decade leading up to a cardiovascular event. This supports earlier research from Chile, where mortality from acute myocardial infarction peaked a decade after very high arsenic exposure levels.

Implications for Public Health

This new evidence raises concerns about the adequacy of current regulatory standards for arsenic in drinking water. While regulatory limits are set to protect against the risk of cancer, this study highlights the need to address other serious health outcomes, particularly heart disease, which remains the leading cause of death worldwide.

The findings suggest that even low-level arsenic exposure can have serious long-term health consequences, reinforcing the need for stricter monitoring and regulation of water quality. “The study underscores the importance of implementing more stringent regulatory standards to protect public health,” Medgyesi noted.

As countries continue to address water contamination issues, this research may prompt a reevaluation of current safety thresholds and lead to stronger measures aimed at reducing arsenic exposure in vulnerable populations.