Paris, France – September 2024

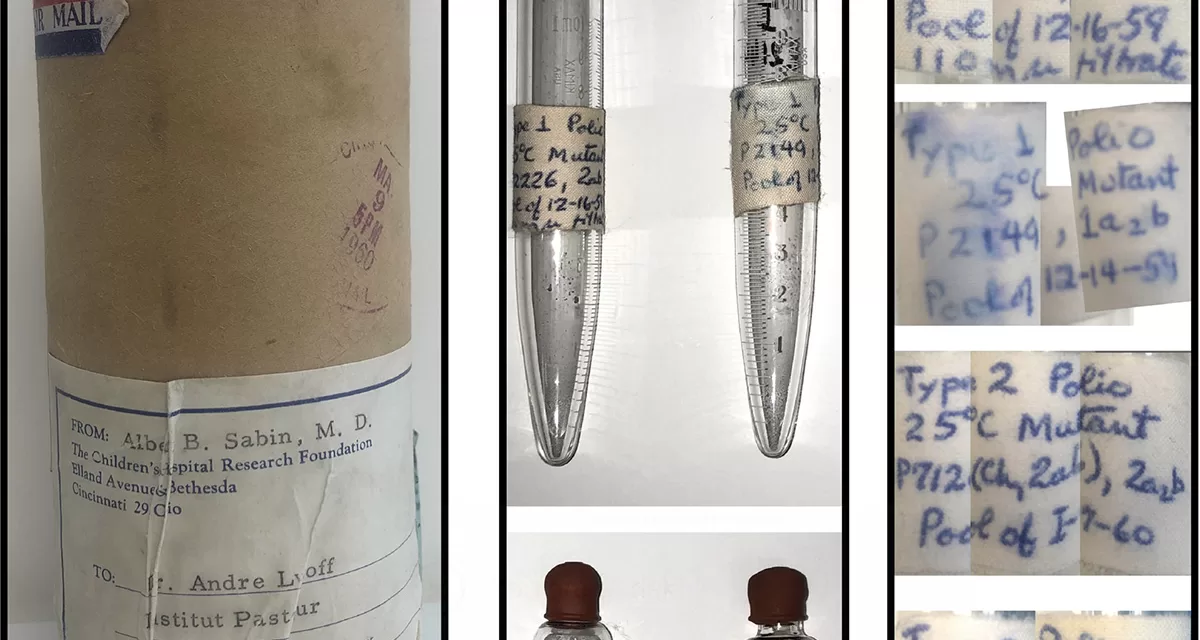

A recent study published in Virus Evolution has raised concerns about the potential for a lab leak involving poliovirus, which could be linked to a case of polio in a four-year-old child in China in 2014. This possibility emerged from research conducted by the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where virologists recently analyzed old poliovirus samples from a virological time capsule sent to them more than 60 years ago by the renowned scientist Albert Sabin.

The investigation began when the Pasteur Institute team sequenced four historical poliovirus samples, which were set to be destroyed as part of a global initiative to eliminate old poliovirus samples. The sequencing aimed to preserve the genetic information of these historical strains. Among the samples was a strain identified as Glenn, which displayed genetic similarities to both a 1950s U.S. poliovirus strain named Saukett A and the virus isolated from the Chinese child, WIV14.

The research revealed that WIV14, previously sequenced at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), was closely related to Saukett A, but not to the Sabin 3 strain used in oral polio vaccines. This discovery led the authors of the study to explore the possibility that the virus infecting the Chinese child might have been contaminated with Saukett A, potentially indicating a lab or vaccine production facility leak rather than a natural evolution from Sabin 3.

The paper, authored by Maël Bessaud and colleagues, highlights that while the exact origin of WIV14 remains unclear, it could suggest that the virus might have been preserved in a laboratory or vaccine production environment before being accidentally released. The authors emphasize that the virus could have been released from any facility globally before its detection in China, and they do not support any specific theory at this time.

The potential link to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, already a focal point in discussions about the origins of COVID-19, has stirred controversy. Despite the lack of evidence connecting WIV to the poliovirus leak, the study has been seized upon by some social media and conservative outlets to suggest another lab-related release. However, experts stress that the virus’s origins remain speculative, with no direct evidence implicating WIV.

Polio, a disease that once paralyzed thousands annually, has been significantly reduced due to effective vaccines developed in the mid-20th century. Today, two of the three original poliovirus strains are eradicated, with the third strain confined to Afghanistan and Pakistan. Efforts to eliminate remaining poliovirus samples and prevent future outbreaks have intensified, leading to rigorous biosafety protocols and disposal procedures.

Historical accidents involving poliovirus have occurred before. In the 2000s, a lab strain was suspected of causing infections in children in India. Additionally, in 2014, a Belgian vaccine facility accidentally released poliovirus particles into the sewage system, although no human infections were reported. More recent incidents include an accidental leak at a vaccine production facility in the Netherlands in 2017 and another case in 2022.

Roland Sutter, former head of polio research at the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, suggests that the poliovirus leak could have originated from various sources, including vaccine production facilities or virology research labs. While a lab leak is plausible, identifying the specific source remains crucial. The investigation into the origins of WIV14 is expected to continue, and experts emphasize the importance of addressing potential lab leaks to prevent similar occurrences in the future.

The Pasteur Institute and other experts stress that while investigating potential lab leaks, it is essential to avoid jumping to conclusions and ensure that findings are based on solid scientific evidence. As the investigation progresses, clarity on the virus’s origin and the circumstances of its release will be critical for understanding and preventing future risks.