Situation at a glance

Since mid-December 2022, Togo has been responding to a meningitis outbreak that has so far resulted in a total of 141 cases and 12 deaths (CFR 8.5%), with almost half of the cases affecting children and young adults between 10 and 19 years of age. Overall, 22 samples have been confirmed as Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Togo is located in the African meningitis belt, with seasonal outbreaks recurring every year. However, the current outbreak is concerning due to different concomitant factors, including the security crisis in the Sahel which causes population movements, and suboptimal surveillance capacity. This is also the country’s first time dealing with a pneumococcal meningitis outbreak.

An incident management system has been established to coordinate the outbreak response activities, and WHO is supporting the shipment of antibiotics (ceftriaxone) to improve case management.

WHO assesses the overall risk posed by this outbreak as high at the national level, moderate at the regional level, and low at the global level.

Description of the situation

On 15 February 2023, the Ministry of Health of Togo officially declared a meningitis outbreak in Oti Sud district, Savanes region, in the northern part of the country. From 19 December 2022 to 2 April 2023, a total of 141 suspected cases of meningitis with 12 deaths (CFR 8.5%) have been reported from Oti Sud district, corresponding to an attack rate of 112 per 100 000 population.

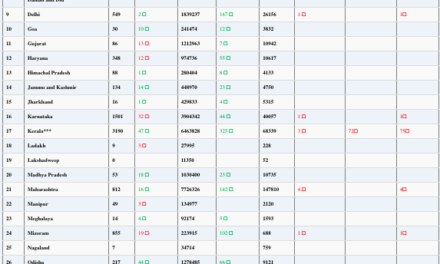

Figure 1. Number of reported meningitis cases and deaths, 19 December 2022 (week 51 of 2022) to 2 April 2023 (week 13 of 2023), Oti Sud district, Savanes region, Togo.

A total of 118 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were collected from suspected cases, of which 22 were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture for Streptococcus pneumoniae at the national reference laboratory (81 samples were negative and the results for 15 samples are pending).

The most affected age group is 10–19 years (47%; n = 66), followed by the ≥30-year age group with 20% (n = 28) of cases, and the 20-29 year age group with 15% (n = 22) of cases. There is no difference in the case distribution by gender, with 71 (53%) cases reported among males.

Togo introduced the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13) in 2014, which is currently administered in three doses at the first, second and third months of life. The administrative PCV13 coverage in the Savanes region is 100% for the third dose, but the immunization history is not available for the individual cases, and it is not known if the serotype(s) involved are covered by the vaccine. Additionally, the most affected age groups were born before the PCV13 introduction in 2014 and could have not received the vaccine.

Epidemiology of the disease

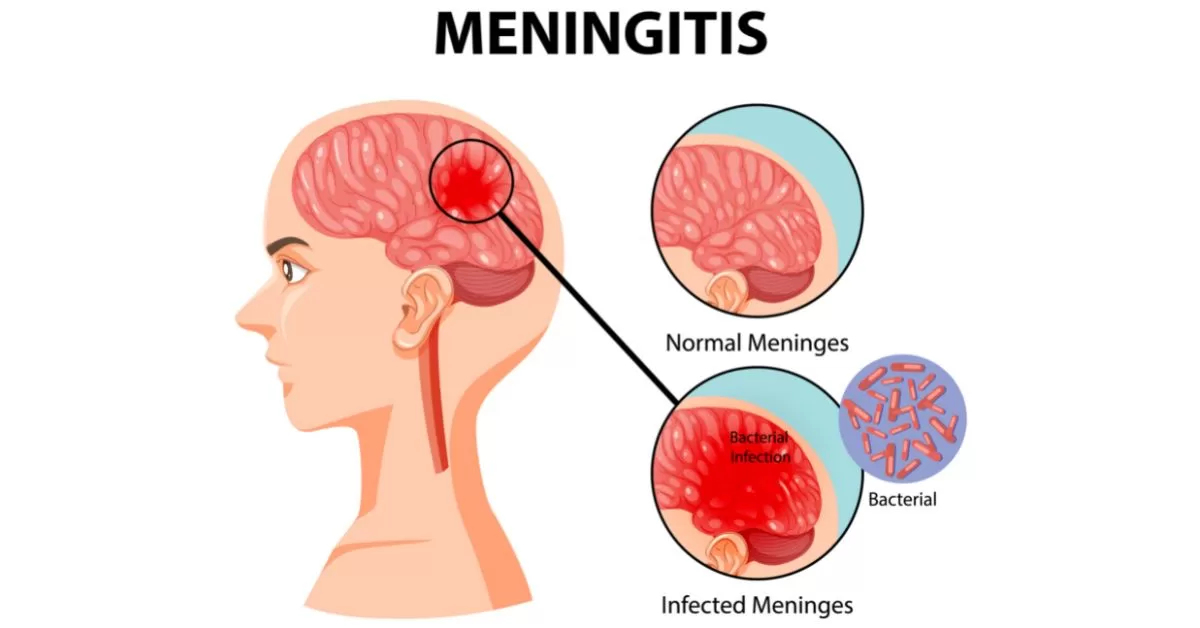

Meningitis is a devastating disease with a high case fatality rate and serious long-term complications (sequelae). It remains a major global public-health challenge. Many organisms can cause bacterial meningitis. Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae type b constitute the majority of all cases of bacterial meningitis and 90% of bacterial meningitis in children. It is estimated that about one million children die of pneumococcal disease every year.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an encapsulated bacterium, and about 90 distinct pneumococcal serotypes have been identified throughout the world, with a small number of these serotypes being able to cause disease. Pneumococci are transmitted by direct contact with respiratory secretions from patients and healthy carriers. Serious pneumococcal infections include pneumonia, meningitis and febrile bacteraemia; otitis media, sinusitis and bronchitis are more common but less serious manifestations. The incubation period is two to 10 days. Pneumococcal meningitis has a high case fatality rate (36%–66%) in the African meningitis belt, requires longer treatment than meningococcal meningitis, and is more frequently associated with severe sequelae.

Diagnosis of bacterial meningitis typically requires lumbar puncture. In the absence of lumbar puncture, diagnosis can only be suspected through clinical examination (but not confirmed, except with a positive blood culture). Culture and PCR are confirmatory tests for bacterial meningitis. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) can support the diagnosis but are not confirmatory. Identification of serotypes or serogroups and susceptibility to antibiotics are important to define control measures. Molecular typing and whole genome sequencing can identify additional differences between strains and inform public health responses.

A range of antibiotics is used to treat meningitis, including penicillin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone. During epidemics of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis, ceftriaxone is the drug of choice. Nevertheless, pneumococcal resistance to antimicrobials is a serious and rapidly increasing problem worldwide.

Two classes of pneumococcal vaccines are currently available. Conjugate vaccines are effective from six weeks of age at preventing meningitis and other severe pneumococcal infections and are recommended for infants and children up to the age of five years, and in some countries for adults aged over 65 years, as well as individuals from certain risk groups. Two different conjugate vaccines are in use that protects against 10 and 13 serotypes, respectively. New conjugate vaccines designed to protect against more pneumococcal serotypes are either in development or have been approved for use in adults. Conjugate vaccines are also effective in preventing nasopharyngeal carriage. A polysaccharide vaccine against 23 serotypes is available but, as for other polysaccharide vaccines, this type of vaccine is considered less effective than conjugate vaccines. It is used mostly in those aged over 65 years to protect against pneumonia, as well as in individuals from certain risk groups. It is not used in children under two years of age and is less useful in protecting against meningitis.

Public health response

- An incident management system has been established to coordinate the outbreak response activities, and coordination meetings are held weekly.

- The national outbreak response plan has been developed and validated.

- Under the leadership of WHO, cross-border meetings are ongoing with Benin and Ghana to share information about outbreak response activities and strengthen preparedness and readiness.

- Health facility managers, community health workers, community relay agents (social workers) and community leaders are being trained on meningitis. Radio spots are broadcasted regarding community-based surveillance and the importance of early healthcare-seeking.

- Active case finding is being conducted in health facilities and in the community.

- Outbreak situation reports are developed by the Ministry of Health with the support of WHO and disseminated to stakeholders involved in response activities.

- WHO has procured and distributed cerebrospinal fluid sample collection and transportation materials to the health facilities in the affected areas.

- WHO is supporting the shipment of antibiotics (ceftriaxone) to improve case management.

- There are ongoing efforts to facilitate the shipment of the samples for further serotyping at the regional reference laboratory.

- WHO is also supporting the mobilization of resources for the implementation of the response plan.

WHO risk assessment

Togo is part of the African meningitis belt and annually records meningitis cases and deaths. Although the country has experience in the management of meningococcal meningitis outbreaks over the past years, the current Streptococcus pneumoniae outbreak is unusual as the country has never managed a pneumococcal meningitis outbreak in the past, and national capacity is limited.

To date, no imported cases have been reported in neighbouring countries. However, several factors are likely to increase the risk of spread, including the country’s location in the African meningitis belt; the epidemic season, which typically runs from January to June; constraints in the provision of vaccination services, which do not allow for optimal vaccination coverage to protect the population; the fact that the main age groups affected by the outbreak are not protected by the routine vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae introduced in Togo in 2014; the security crisis in the Sahel, affecting the Savanes region, hampering public health interventions and causing population movements; the precarious economic conditions in the country, particularly in the Savanes region; and the suboptimal surveillance capacity for early case detection, diagnosis and treatment in the Oti Sud district. Neighbouring countries are also in the African meningitis belt, and the Oti Sud district borders Ghana and Benin, making it possible for the disease to spread to other countries in the region.

Considering the above-described situation, WHO assesses the overall risk posed by this outbreak as high at the national level, moderate at the regional level, and low at the global level.

WHO advice

Early diagnosis and appropriate case management are essential, given the high case fatality and risk of developing sequelae due to pneumococcal meningitis. Prompt antibiotic treatment should be ensured for a duration of 10-14 days. Active community-based case-finding and community engagement should be implemented to inform the communities of the signs of meningitis and the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. The collection of detailed epidemiological and microbiological data, including serotyping, is essential to inform the pneumococcal meningitis control strategy.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines are effective in preventing meningitis and other serious pneumococcal infections. To date, the available data do not support recommendations for reactive vaccination campaigns against pneumococcal meningitis outbreaks. Recommendations for the use of pneumococcal vaccine in community outbreak settings were discussed by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) in October 2020, with one main conclusion being that more research and evidence gathering was needed from countries of the African meningitis belt, in order to develop a strategy for pneumococcal meningitis outbreak prevention and response.

WHO, with the support of many partners, has developed a Global Roadmap to defeat meningitis by 2030. Concerted actions to achieve this goal are organized around five interrelated pillars:

- Prevention and epidemic control by developing new affordable vaccines, achieving high immunization coverage, improving prevention strategies, and responding to epidemics;

- Diagnosis and treatment through rapid confirmation of meningitis cases and optimal patient management;

- Meningitis surveillance to guide prevention and control;

- Management of those affected by meningitis through early case detection and improved access to management of complications; and

- Advocacy and engagement to ensure high awareness of meningitis, promote country commitment and affirm the right to prevention, care, and follow-up services.Based on the information currently available on this outbreak, WHO does not recommend any travel or trade restrictions for Togo.

Further information

- Meningitis – WHO Fact sheet

- Meningitis – Health topics, WHO

- WHO – Pneumococcal Disease

- Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines – WHO position paper

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, meeting, 5 – 7 October 2020

- Cadre pour la mise en œuvre de la stratégie mondiale pour vaincre la méningite d’ici à 2030 dans la région africaine de l’OMS

- Defeating meningitis by 2030: a global road map. Geneva : World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026407

- Weekly epidemiological record, no 23, 10 June 2016

- WHO. Vaccination schedule for Togo

- WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: Immunization Togo 2022 country profile

- WHO Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals: Pneumonia

Citable reference: World Health Organization (11 April 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Pneumococcal meningitis – Togo. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON455