A groundbreaking study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has enabled a paralyzed man to control a robotic arm using only his thoughts. This achievement, published in the journal Cell, marks a significant step forward in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology.

The study participant, who had been paralyzed by a stroke years earlier, was able to grasp, move, and release objects just by imagining himself performing these actions. The key to this advancement was a brain-computer interface that successfully functioned for an unprecedented seven months without needing adjustments. Previously, such devices typically lost effectiveness after only a few days.

AI and Human Learning: A Powerful Combination

The BCI relies on an artificial intelligence (AI) model capable of adapting to the subtle shifts in brain activity that occur as a person repeats a movement—or, in this case, imagines performing one. Dr. Karunesh Ganguly, a professor of neurology and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, emphasized the importance of this human-AI interaction.

“This blending of learning between humans and AI is the next phase for these brain-computer interfaces,” Ganguly said. “It’s what we need to achieve sophisticated, lifelike function.”

Unlocking the Brain’s Potential

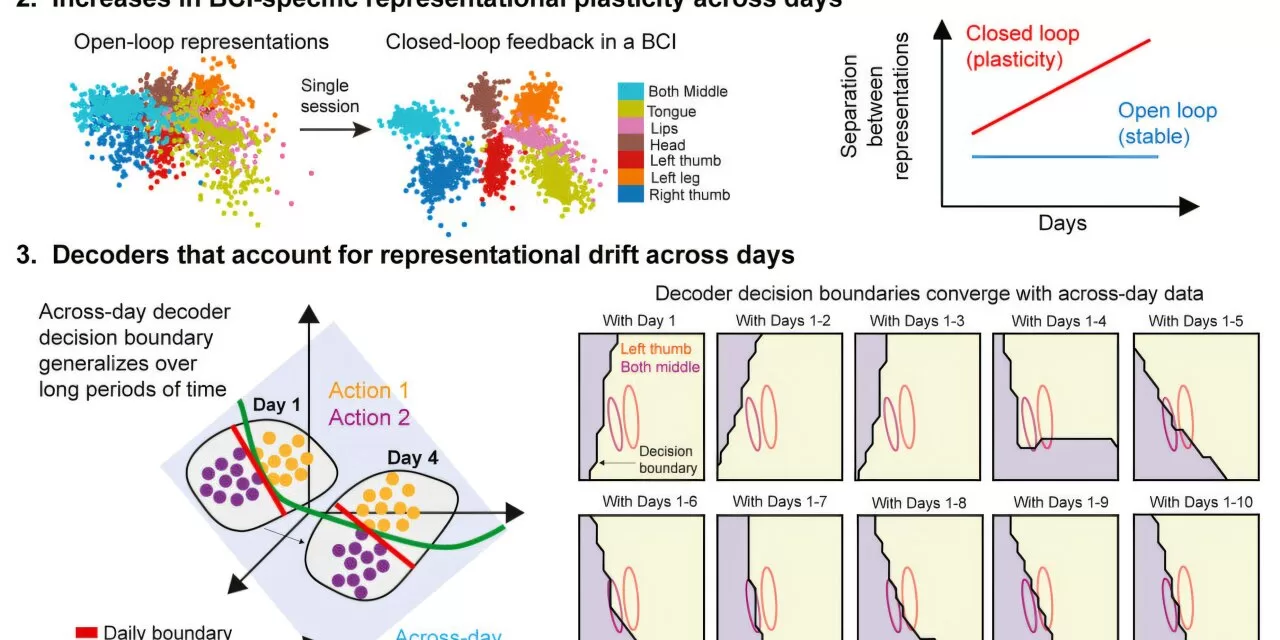

Through previous research on animals, Ganguly observed that patterns of brain activity representing specific movements changed slightly each day. He suspected the same phenomenon occurred in humans, explaining why BCIs previously struggled with long-term reliability.

To test this theory, Ganguly and neurology researcher Dr. Nikhilesh Natraj worked with a study participant who had tiny sensors implanted on the surface of his brain. These sensors detected brain activity as he imagined moving different body parts.

While the participant could not physically move, his brain continued to generate movement signals. The BCI recorded these patterns and allowed researchers to analyze how they shifted daily. The breakthrough came when the AI was programmed to adapt to these shifts, significantly extending the device’s functional lifespan.

From Virtual Training to Real-World Application

The next challenge was training the participant to use the robotic arm effectively. Initially, his movements lacked precision. To improve accuracy, researchers introduced a virtual robot arm that provided feedback, allowing the participant to refine his visualized movements.

After practicing with the virtual model, the participant transitioned to a real robotic arm. He quickly gained control, successfully picking up and manipulating objects. In later trials, he performed complex tasks such as opening a cabinet, retrieving a cup, and positioning it under a water dispenser.

Even months after initial training, the participant could still control the robotic arm with just a brief 15-minute “tune-up” to recalibrate for changes in his brain’s movement representations.

A New Future for Paralyzed Individuals

Ganguly is now working to refine the AI to improve the robotic arm’s speed and fluidity. Future research will explore how this technology can be implemented in a home setting, offering new independence to individuals with paralysis.

“I’m very confident that we’ve learned how to build the system now and that we can make this work,” Ganguly said.

For people living with paralysis, regaining control over basic daily activities—such as feeding themselves or getting a drink of water—could be life-changing.

The study’s authors include Sarah Seko and Adelyn Tu-Chan of UCSF, along with Reza Abiri of the University of Rhode Island.

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or professional advice. The research is still in the experimental stage, and further studies are required to determine the long-term effectiveness and accessibility of brain-computer interface technology for broader clinical use.