According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over 684,000 Americans are diagnosed with “obesity-associated” cancers each year.

The incidence of many of these cancers has been increasing, especially among younger people, which contrasts with the overall decline in cancers not linked to excess weight, such as lung and skin cancers.

Is obesity the new smoking? Not exactly.

Drawing a direct link between excess fat and cancer is more complex than it is with tobacco. While about 42% of cancers — including common types like colorectal and postmenopausal breast cancers — are considered obesity-related, only about 8% of cancer cases are attributed to excess body weight. People often develop these cancers regardless of their weight.

Although substantial evidence points to excess body fat as a cancer risk factor, it is unclear at what point excess weight impacts cancer risk. For instance, is gaining weight later in life better or worse for cancer risk than being overweight from a young age? Another unanswered question is whether losing weight in adulthood can alter this risk. In other words, how many of those 684,000 diagnoses could have been prevented if people had lost excess weight?

“There’s a lot we don’t know,” said Jennifer W. Bea, PhD, associate professor of health promotion sciences at the University of Arizona.

A Consistent but Complicated Relationship Given the growing incidence of obesity, which currently affects about 42% of US adults and 20% of children and teenagers, numerous studies have explored the potential effects of excess weight on cancer rates.

Most evidence comes from large cohort studies, which do not establish causation but show consistent associations. “What we know is that a higher body mass index (BMI) — particularly in the obese category — leads to a higher risk of multiple cancers,” said Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, MD, MPH, co-director of the Colon and Rectal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

A 2016 report in The New England Journal of Medicine by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) analyzed over 1000 studies on body fat and cancer. It linked excess body weight to over a dozen cancers, including some of the most common and deadly, such as esophageal adenocarcinoma, endometrial cancer, kidney, liver, stomach (gastric cardia), pancreatic, colorectal, postmenopausal breast, gallbladder, ovarian, and thyroid cancers, as well as multiple myeloma and meningioma. There is also limited evidence linking excess weight to other cancer types, including aggressive prostate cancer and certain head and neck cancers.

Many of these cancers are also associated with factors that lead to, or coexist with, overweight and obesity, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and metabolic conditions like diabetes. This indicates a complex web where high BMI both directly affects cancer risk and is part of a causal pathway of other factors.

Preclinical research points to multiple ways excess body fat might contribute to cancer, said Karen M. Basen-Engquist, PhD, MPH, professor at the Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Services at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. One broad mechanism is chronic systemic inflammation, as excess fat tissue can raise levels of substances like tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6, which fuel inflammation. Excess fat also contributes to hyperinsulinemia, promoting the growth and spread of tumor cells.

The underlying reasons vary by cancer type. For hormonally driven cancers like breast and endometrial cancer, excess body fat may alter hormone levels, spurring tumor growth. For example, extra fat tissue may convert androgens into estrogens, feeding estrogen-dependent tumors. This may explain why excess weight is associated with postmenopausal but not premenopausal breast cancer.

How Big Is the Effect? While more than a dozen cancers are consistently linked to excess weight, the strength of these associations varies. In the 2016 IARC analysis, severe obesity increased the risk of endometrial cancer sevenfold and esophageal adenocarcinoma 4.8-fold compared to a normal BMI. For other cancers, the risk increases were more modest, such as 10% for ovarian cancer and 30% for colorectal cancer. For postmenopausal breast cancer, every five-unit BMI increase was associated with a 10% relative risk increase.

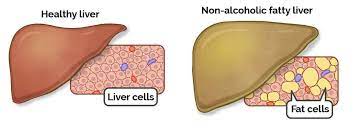

A 2018 American Cancer Society study estimated the proportion of cancers in the US attributable to modifiable risk factors, finding that smoking accounted for 19% of cancer cases, while excess weight accounted for 7.8%. Weight played a larger role in certain cancers, such as 60% of endometrial cancers and roughly one third of esophageal, kidney, and liver cancers.

CDC data show that obesity-related cancers are rising among women younger than 50, especially among Hispanic women. Some less common obesity-related cancers, such as stomach, thyroid, and pancreatic cancers, are also increasing among Black and Hispanic Americans. This may contribute to growing cancer disparities, said Leah Ferrucci, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of epidemiology at Yale School of Public Health. However, the evidence is limited due to the underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic individuals in studies.

When Do Extra Pounds Matter? When does excess weight or weight gain impact cancer risk? Is weight gain in middle age as hazardous as being overweight from a young age? Some evidence suggests there is no “safe” time for putting on excess weight.

A recent meta-analysis concluded that weight gain at any point after age 18 is associated with incremental increases in the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open found a similar pattern with colorectal and other gastrointestinal cancers, showing that sustained overweight or obesity from age 20 through middle age increases the risk of these cancers after age 55.

The timing of weight gain did not seem to matter, as those who gained weight after age 55 faced similar risks. Recent studies have also noted a rise in early-onset cancers, particularly gastrointestinal cancers, diagnosed before age 50. The increasing prevalence of obesity among young people may partly explain this trend, supported by data from the Nurses’ Health Study II showing that women with obesity had double the risk for early-onset colorectal cancer compared to those with a normal BMI.

Does Weight Loss Help? While high BMI is a cancer risk factor, there is limited data on whether weight loss reduces this risk. Some research on substantial weight loss after bariatric surgery shows encouraging results. A study in JAMA found that among 5053 people who underwent bariatric surgery, 2.9% developed an obesity-related cancer over 10 years compared to 4.9% in the nonsurgery group.

Modest weight loss through diet and exercise may also lower the risk of postmenopausal breast and endometrial cancers. A 2020 pooled analysis found that women aged ≥ 50 who lost as little as 2.0-4.5 kg and kept it off for 10 years had a lower risk of breast cancer than women whose weight remained stable. Losing more weight, around 20 pounds or more, further lowered cancer risk.

However, other research suggests the opposite. A recent analysis found that people who lost weight within the past two years through diet and exercise had a higher risk for various cancers compared to those who did not lose weight. Overall, though, the increased risk was low.

Regardless of what the research shows, Karen M. Basen-Engquist emphasized that risk factors, including obesity, should not be used to blame individuals. “With obesity, behavior certainly plays into it,” she said, “but there are many socially determined influences on our behavior.”

Clinicians should consider individual circumstances and set realistic expectations. People with obesity should not feel they must become thin to be healthier, nor should they feel they must go from being sedentary to exercising several hours a week.

“We don’t want patients to feel that if they don’t get to a stated goal in a guideline, it’s all for naught,” Meyerhardt said.