In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Northeastern University researchers are working on innovative epidemic models that incorporate collective behavioral patterns. These models aim to help policymakers make better decisions, not only for future pandemics but for other public crises as well.

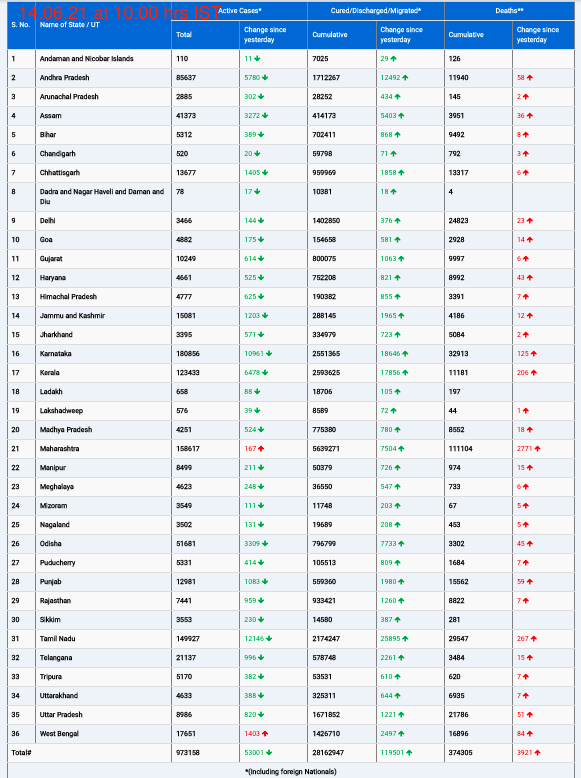

Social distancing, a key strategy during the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, proved effective in reducing the transmission of COVID-19—where it was practiced. However, adoption of the strategy was uneven across different regions, presenting a challenge for epidemiologists attempting to forecast the virus’s spread. Policymakers faced an additional challenge: how could they have anticipated which regions would embrace social distancing and how might they have adjusted messaging in areas resistant to it?

Northeastern University professors Babak Heydari, Gabor Lippner, Daniel T. O’Brien, and Silvia Prina are leading a new project titled “No One Lives in a Bubble: Incorporating Group Dynamics into Epidemic Models.” Their work focuses on understanding the behavior of people during epidemics, a factor Heydari believes is just as crucial as understanding the behavior of the virus itself.

Heydari, the project’s principal investigator and associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, points out that during early COVID-19 policy debates, an important insight was often overlooked: people adjust their behavior based on their perception of the virus. “It’s not just the virus that’s moving,” he explained, “it’s also people adjusting their behavior according to the virus.”

For example, social “pods” or “bubbles” were a common method people used to balance the risks of infection with the need for social interaction. The formation of these pods extended household sizes, impacting how the virus transmitted within communities. Additionally, regional variations in risk-mitigation norms, such as attitudes toward mask-wearing and social distancing, contributed to the differing transmission rates across the country and the world.

Integrating Human Behavior into Epidemic Models

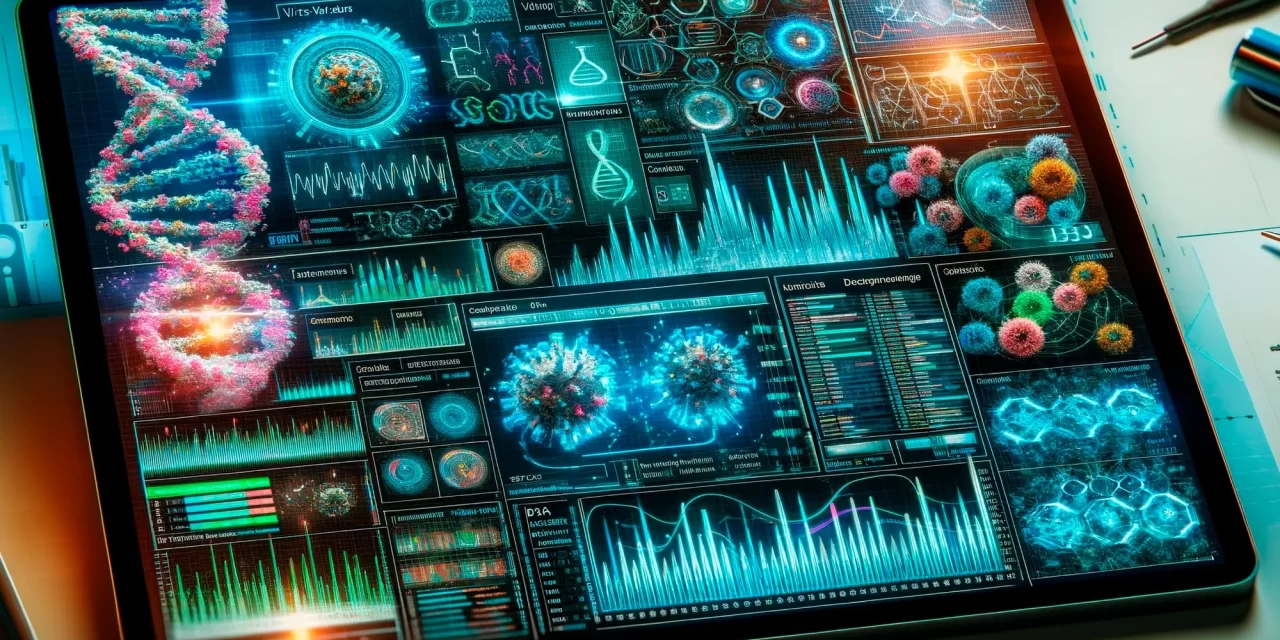

Current epidemic models often struggle to predict the complex, group-level responses to policies. Heydari and his team aim to address this gap by using computational models to integrate collective behaviors into existing models, improving their accuracy and making them more useful for future policymaking.

Lippner, an associate professor of mathematics and expert in mathematical dynamic models, will develop the theoretical framework needed to represent how social groups interact. Meanwhile, Prina, a professor of economics, will focus on extracting causal relationships from real-world data, which will be crucial in shaping more effective policy designs.

O’Brien, a professor of public policy and criminology, brings expertise in social network analysis. He points out that individuals have varying levels of contact with different social groups, creating bridges through which infections—and other social norms—can spread.

According to the researchers, these new models can extend beyond epidemic forecasting to other public crises, such as natural disasters or social issues like the opioid epidemic. Heydari explains that understanding how to steer collective behavior in these scenarios, rather than relying solely on mandates, could prove to be a more effective intervention strategy.

A Future of Adaptive Models

Looking ahead, the team envisions models that are adaptive and responsive to real-time data, enhanced by advances in artificial intelligence. These models will provide policymakers with deeper insights, allowing for more targeted interventions during crises.

The project is still in its early stages, but the Northeastern researchers are optimistic about its potential to improve public health responses in future pandemics and beyond. By integrating collective behavior into epidemic models, they aim to offer a new tool for steering societies toward the social good during times of crisis.