With the proliferation of online scams and misinformation, researchers are delving into the psychology behind why people are often deceived on the internet. A recent study conducted by researchers at University College London (UCL) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), published in Communications Psychology, sheds light on the factors influencing individuals’ ability to detect lies online.

Co-authors Tali Sharot and Sarah Zheng emphasized the urgent need to understand why people fall victim to online scams, particularly in light of increasing financial losses worldwide due to deceptive practices. “People all around the world have been losing billions to online scams year on year,” they stated. “Now, before we can help people detect online scams, we need to understand why people fall for them in the first place.”

The study builds upon previous research on lie detection, which primarily focused on offline contexts where subtle cues like tone of voice and body language play a significant role. In the online realm, however, such cues are often absent, posing a unique challenge for detecting deception.

To investigate this phenomenon, researchers conducted a series of experiments involving 310 participants engaged in an online card game. Participants were tasked with assessing the honesty of their fellow players based on their interactions during the game. Notably, players had the option to lie about the cards they received, potentially gaining a financial advantage over others.

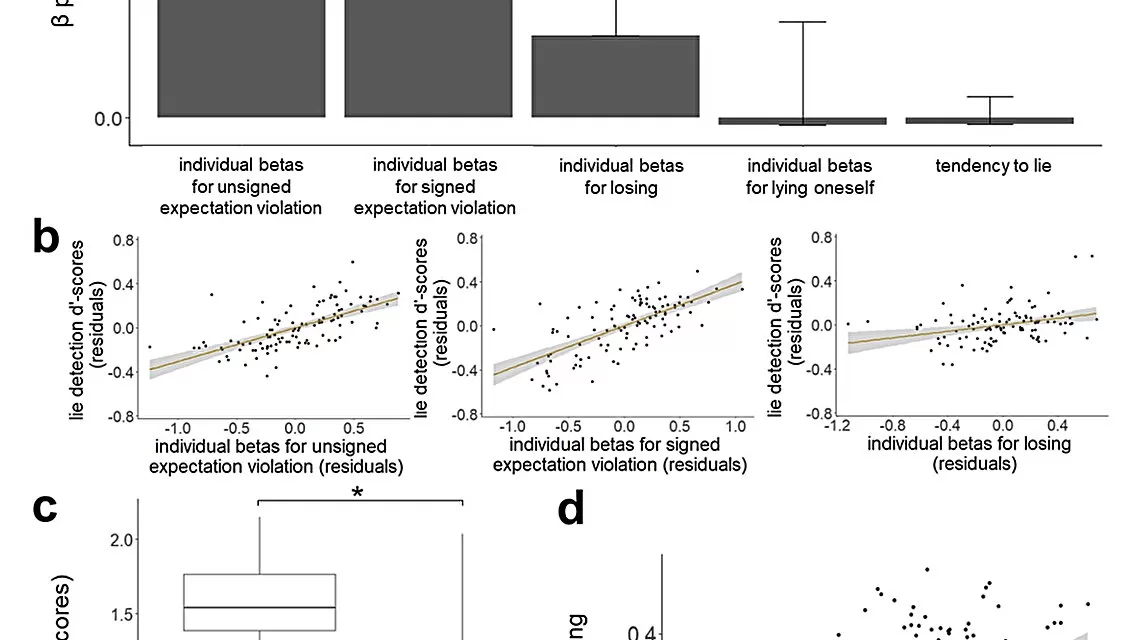

The results revealed intriguing patterns in participants’ behavior. Those who had themselves lied during the game were more suspicious of others, suggesting a tendency to project their own behavior onto others. Additionally, participants were more likely to doubt the honesty of others when they reported holding statistically unlikely cards, indicating a reliance on statistical cues.

Furthermore, the study compared participants’ lie detection abilities to those of an artificial lie detector. It found that individuals tended to rely excessively on their own honesty or dishonesty, while overlooking statistical cues—a finding with significant implications for scam detection online.

“These findings imply that honest people may be particularly susceptible to scams because they are the least likely to suspect a lie and thus detect a scam,” Sharot and Zheng explained.

Moving forward, the researchers propose the development of an “adversarial training” approach to enhance scam detection. This method involves exposing individuals to scam creation scenarios, potentially improving their ability to identify deceptive practices online.

The study’s insights offer valuable guidance for policymakers and technology firms striving to combat online scams and misinformation. By understanding the psychological factors at play, efforts can be directed toward empowering internet users to navigate the digital landscape safely and securely.

“Our findings led to the idea of creating an ‘adversarial training’ to help people detect online scams,” Sharot and Zheng added. “Initial results look promising, and we now aim to test this further in other contexts.”