Published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, the study highlights the significant pediatric tuberculosis (TB) risk in South Africa’s high-burden communities.

A recent study reveals that children in regions with high TB transmission rates are at a much greater risk of contracting the disease than previously thought. According to findings led by the Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), the University of São Paulo, and the University of Cape Town, 10% of children in these areas may develop TB by age 10, underscoring a critical need for heightened awareness and prevention efforts.

Tuberculosis affects an estimated 1.2 million children worldwide annually, leading to the deaths of approximately 200,000 children. However, the long-term risk of TB in children, particularly in real-world settings, remains under-studied. This new study fills a gap by following children through the first decade of life in a high-burden community near Cape Town, South Africa.

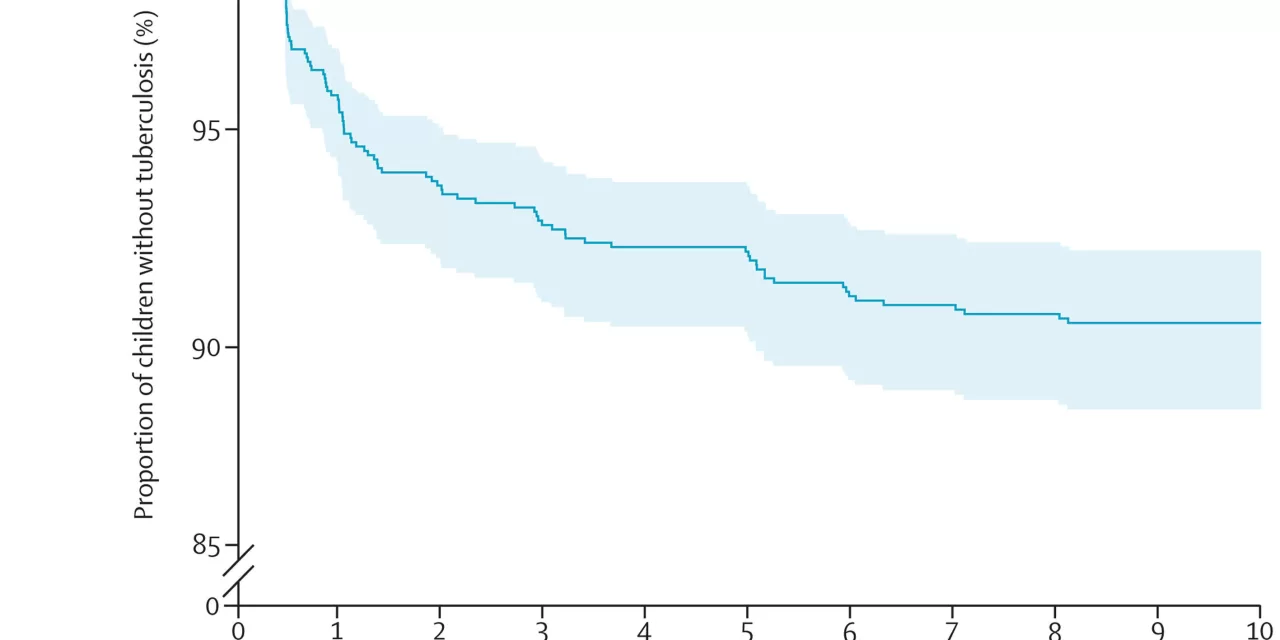

The research team, led by Dr. Leonardo Martinez, assistant professor of epidemiology at BUSPH, found that infection rates were high among children, with 4-9% testing positive each year. By age 10, more than 10% of the children involved had developed active TB. “These results are striking and show that children in these communities in South Africa are at extraordinarily high risk,” said Dr. Martinez. He highlighted that in comparison, South African children are at much greater risk than their U.S. counterparts, indicating a significant public health crisis.

For this study, the researchers tracked 1,143 children born to 1,137 women enrolled in the Drakenstein Child Health Study between 2012 and 2023. Testing at various intervals revealed that children’s cumulative risk of TB infection reached 36% by age eight, with infection rates highest during infancy. Although the risk decreased with age, the researchers noted that one in 10 children still developed active TB by age 10, a finding that poses potential long-term health risks.

“Despite reasonable nutrition and low HIV prevalence, there was an extraordinarily high, concerning rate of TB infection and disease in this cohort,” noted Dr. Heather Zar, the study’s co-senior author and principal investigator of the Drakenstein Child Health Study. Many cases of TB were discovered during treatment for acute pneumonia, highlighting the importance of TB screening in children with pneumonia in high-burden areas.

Although TB is treatable with medication, most children in the study who developed TB disease had not received preventive treatment, pointing to a crucial gap in healthcare access. “Preventive treatments were broadly effective for those who accessed care, but only a small proportion of the cohort did so,” the study found.

This new data is vital in advancing the World Health Organization’s (WHO) goal of reducing TB incidence by 80% and deaths by 90% by 2030. Decreasing pediatric TB, the researchers argue, is essential for achieving this aim, especially in high-burden areas like South Africa. “If we are to reduce pediatric tuberculosis globally, a multisectoral approach is needed that brings together researchers, policymakers, health care workers, funders, and advocates to find comprehensive solutions,” said Dr. Martinez.

The study’s findings underscore the urgent need for expanded TB prevention efforts targeting children, particularly in high-risk settings, to protect against both immediate and lifelong health impacts.

For more information, refer to the study Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and tuberculosis disease in the first decade of life: a South African birth cohort study, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health (2024).