The quest for cancer vaccines, long seen as the “holy grail” of oncology, is gaining renewed momentum thanks to advancements in immunotherapy and vaccine technology. While past efforts have often ended in disappointment, recent breakthroughs are sparking optimism among scientists and clinicians.

A History of Highs and Lows

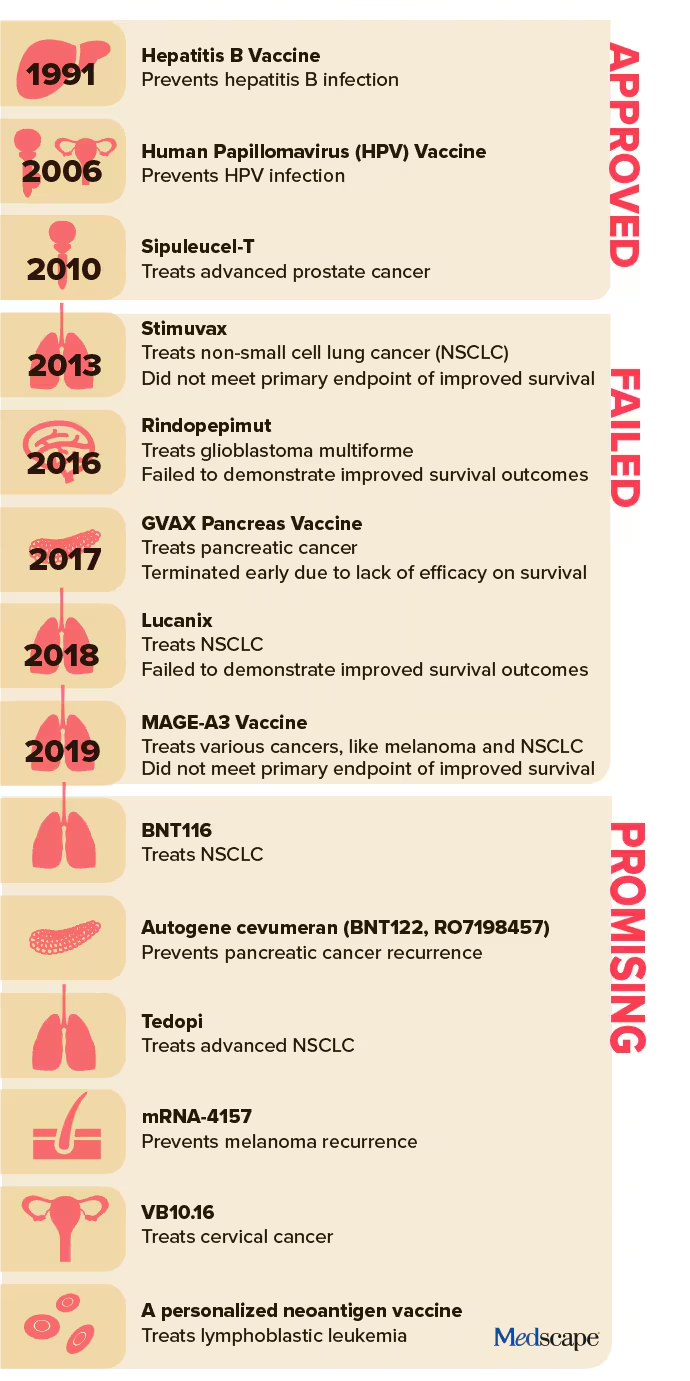

Cancer vaccines have seen sporadic success. The HPV vaccine dramatically reduced HPV-related cancers, and the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine has effectively prevented early-stage bladder cancer recurrence. But therapeutic cancer vaccines have largely struggled to deliver on their promise.

Failures in the past decade include high-profile clinical trials for glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) vaccines. Many promising candidates failed to demonstrate significant survival benefits, dampening enthusiasm and halting research programs.

Despite setbacks, these challenges laid the groundwork for recent advances. Dr. Larry W. Kwak, deputy director at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, attributes the renewed interest to improvements in mRNA technology, rapid production capabilities, and a better understanding of immune response modulation.

“The timing wasn’t right before,” Kwak noted. “Now, it’s a different environment and a different time.”

The New Era of mRNA Vaccines

At the forefront of this revival are mRNA-based vaccines, leveraging the same technology that enabled COVID-19 vaccines. These personalized therapies target patient-specific neoantigens — proteins unique to cancer cells — to activate the immune system against tumors.

Key examples include:

- mRNA-4157: Developed by Merck and Moderna, this melanoma vaccine has shown promise in phase 2 trials. Patients receiving the vaccine with pembrolizumab had nearly half the risk of melanoma recurrence or death compared to those on pembrolizumab alone. Phase 3 trials are now underway.

- BNT116: BioNTech’s NSCLC vaccine targets specific antigens on lung cancer cells. Clinical trials are evaluating its potential to treat advanced disease.

Additional research includes a pancreatic cancer vaccine, which has yielded promising results in early-stage trials. In a cohort of 16 patients, half responded to the vaccine, with six remaining recurrence-free after three years.

A Turning Point or Familiar Risks?

While excitement builds, caution persists. Therapeutic cancer vaccines have a long history of early promise followed by large-scale trial failures. For example, a phase 3 trial for a glioblastoma vaccine in 2016 was terminated for lack of efficacy, echoing a broader trend of late-stage disappointments.

Dr. Kwak emphasized the importance of trial design, advocating for studies that extract meaningful insights even from negative outcomes. “Failures in large clinical trials can put a chilling effect on cancer vaccine research,” he said. “We must focus on learning what works, what doesn’t, and why.”

Kwak’s recent work on lymphoma vaccines exemplifies this approach. A personalized neoantigen vaccine trial for untreated lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma showed stable disease or better in all patients, with a median progression-free period exceeding six years. These findings inform the design of next-generation trials, pairing vaccines with agents targeting specific tumor characteristics.

The Path Forward

Experts remain optimistic that cancer vaccines could revolutionize oncology. Dr. Catherine J. Wu of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute sees a future where personalized and “off-the-shelf” vaccines become standard. “Focusing on neoantigens from driver mutations across tumor types could enable progress,” she said.

However, success hinges on balancing optimism with rigorous science. “We’ve seen glimpses that cancer vaccines can work,” said Kwak. “It’s about tweaking the science to achieve consistent results.”

While it’s too soon to declare victory, the horizon looks brighter than ever for cancer vaccines. If ongoing trials deliver, they could usher in a new era of personalized cancer treatment — and renewed hope for patients worldwide.