Background

Behavioral science has long observed that individuals tend to be more cooperative with members of their own group—whether bonded by language, country of origin, or political ideology—than with outsiders. This phenomenon, known as parochialism or in-group favoritism, is prevalent worldwide. Traditionally, it was inferred that group members would also be more likely to compete with outsiders than with each other. However, the relationship between in-group cooperation and competition has not been extensively studied independently.

The Study

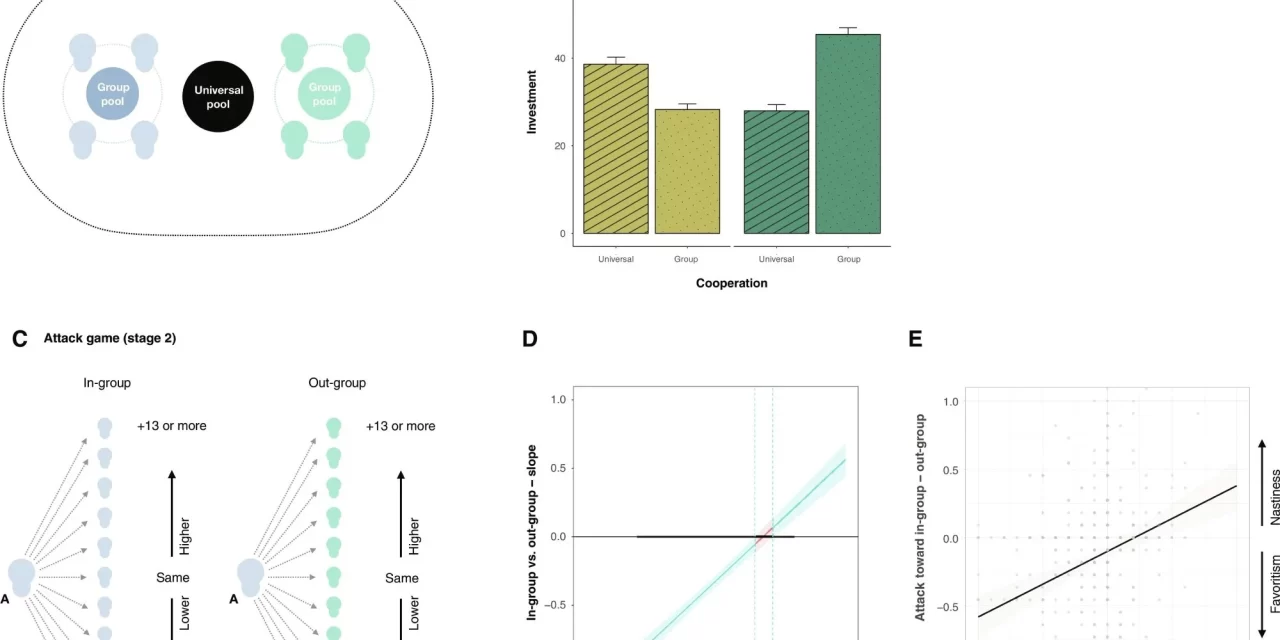

A recent study sought to explore whether in-group favoritism also manifests in competitive scenarios, using data from nearly 13,000 participants across 51 countries. Participants, representing a broad demographic range, were subjected to an online survey designed in English and translated into various languages. They were asked to make 54 decisions involving investments in standardized monetary units (MU), split equally between attacker and defender roles, against opponents from different countries.

Each decision involved interactions with an opponent whose nationality was disclosed just prior to the decision. Among the 27 decisions in each block, one interaction was with a same-nationality opponent, one with an unidentified individual, and the rest with different-nationality opponents.

In a secondary study, 552 participants from Nairobi, Kenya, representing different ethnocultural groups, underwent the same experiment. This segment aimed to observe interactions beyond online international contexts, focusing on communities with histories of both conflict and peace.

Major Findings

The study uncovered a surprising trend: individuals were more competitive with members of their own group than with outsiders. This behavior, termed the “nasty neighbor effect,” was evident in the attacker-defender contest and the prisoner’s dilemma game theory scenarios, where individuals could choose to cooperate for mutual benefit or betray for personal gain.

Cultural variations in the “nasty neighbor effect” were noted, correlating with egalitarian and hierarchical values and wealth. The researchers also observed similar behaviors in other species, suggesting possible evolutionary roots for this phenomenon.

Conclusions

The findings challenge the notion that in-group favoritism is uniformly cooperative. While cooperation within groups is often beneficial, competition among group members can emerge, particularly in resource-scarce situations. This “nasty neighbor” behavior operates independently of the general cooperation and trust within groups, indicating a complex interplay between cooperation and competition.

Journal Reference

Romano, A., Gross, J., & De Dreu, C.K.W. The nasty neighbor effect in humans. Science Advances, 10(26). DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adm7968, Science Advances.