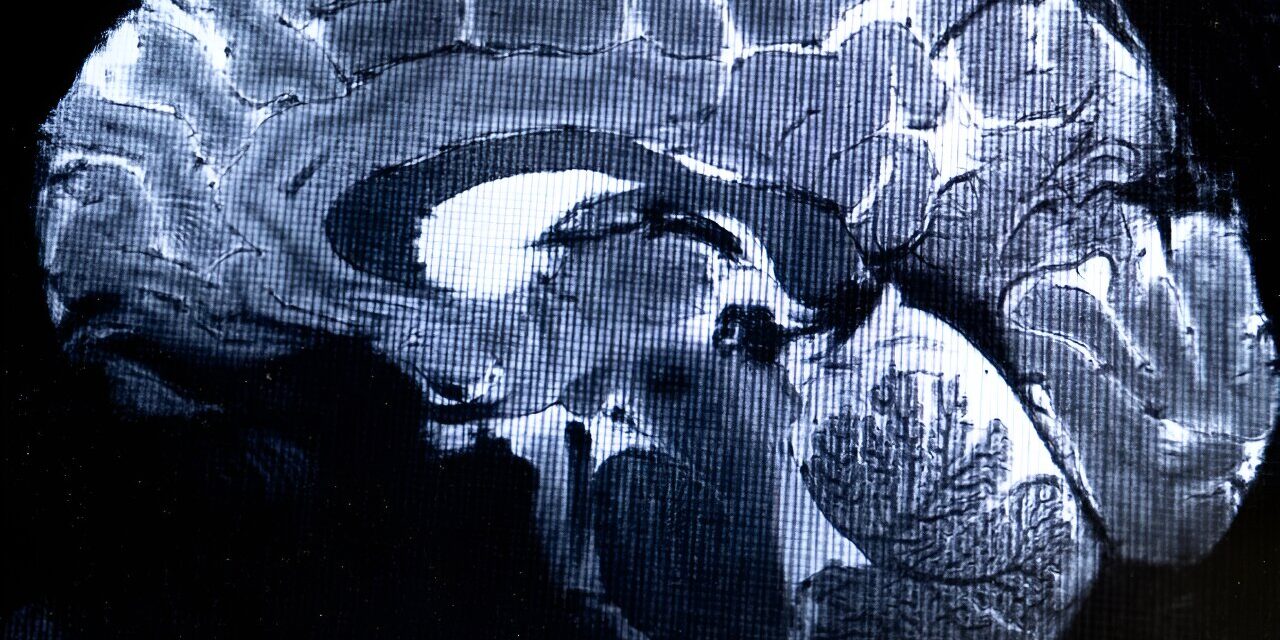

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at Mass General Brigham has identified a common brain circuit responsible for creativity. By analyzing data from 857 participants across 36 fMRI studies, scientists discovered that various brain regions activated by creative tasks are interconnected within a single brain network. The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, suggest that individuals with brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases affecting this circuit may exhibit increased creativity.

Dr. Isaiah Kletenik, co-senior author of the study and neurologist at the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, emphasized the research’s primary objectives. “We wanted to answer the questions, ‘What brain regions are key for human creativity and how does this relate to the effects of brain injuries?’” he explained.

The study was led by Julian Kutsche, MA, in collaboration with researchers from multiple institutions, including Boston Children’s Hospital, University College London, and the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences. Dr. Michael D. Fox, co-senior author and director of the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, highlighted the significance of their discovery. “We found that many complex human behaviors, such as creativity, don’t map to a specific brain region but do map to specific brain circuits,” he stated.

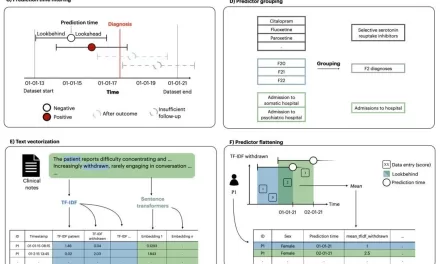

To explore this phenomenon, researchers examined fMRI data to identify brain regions activated during creative activities like drawing, writing, and music composition. They then assessed cases where individuals experienced changes in creativity due to brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases. The study revealed that those with increased creativity often exhibited disruptions in the right frontal pole, a brain region responsible for rule-based behaviors and self-monitoring.

Kutsche noted that the suppression of activity in this area aligns with the hypothesis that creativity requires the inhibition of self-censorship, enabling more fluid idea generation. “To be creative, you may have to turn off your inner critic to allow yourself to find new directions and even make mistakes,” he said.

Dr. Kletenik further explained how the findings might help understand why certain neurodegenerative diseases can lead to either increased or decreased creativity. Additionally, the results suggest potential avenues for brain stimulation techniques to enhance creative abilities. However, he cautioned that the identified brain circuit is not the sole determinant of creativity, emphasizing that numerous brain regions contribute to different creative processes.

“We are learning more about neurodiversity and how brain changes considered pathological may actually improve function in some ways,” Kletenik concluded. “These findings provide deeper insights into how our brain’s circuitry can influence and unlock creativity.”

Disclaimer: The findings of this study are based on neuroimaging and lesion mapping techniques and should not be interpreted as a definitive explanation of human creativity. Further research is required to explore additional factors influencing creative abilities. This article does not constitute medical advice.