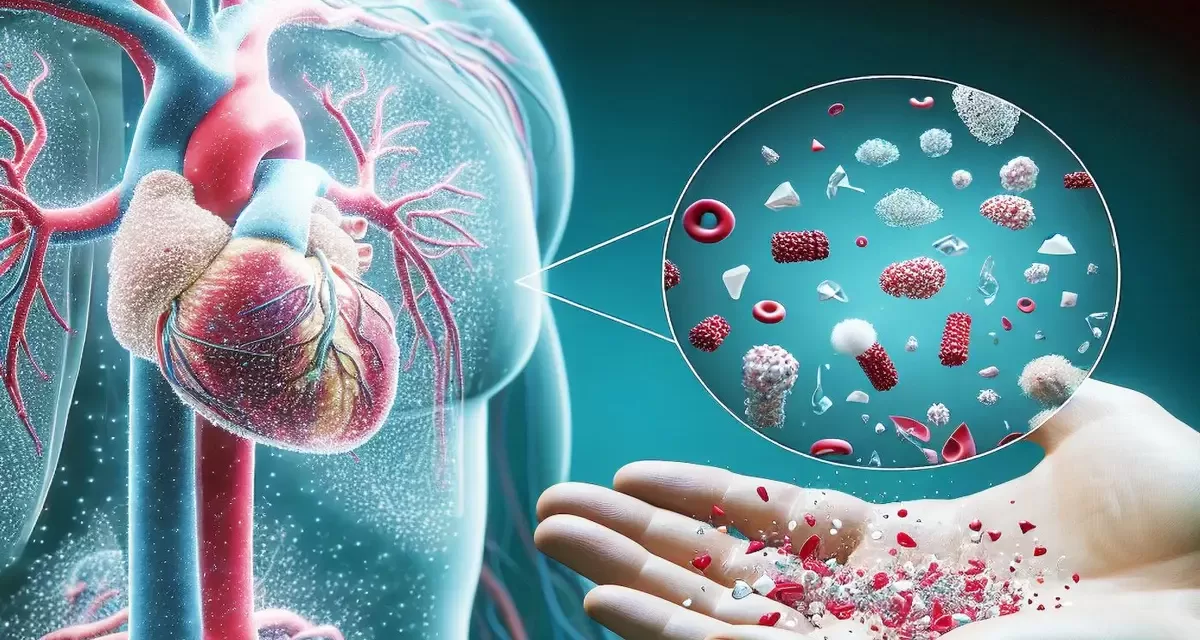

In a concerning revelation, recent research has shown that microplastic pollution has infiltrated even the lives of newborns, raising alarm bells about the pervasive presence of these pollutants in our environment. As our world becomes increasingly saturated with plastic—from our homes and cars to our food—these tiny remnants, smaller than a grain of sand, have established themselves in every aspect of our ecosystem and bodies.

A pivotal study published in Science of the Total Environment, led by researchers from Rutgers Health, highlights this growing crisis.

Understanding Microplastics and Nanoplastics

Microplastics are defined as plastic fragments smaller than 5 millimeters, while nanoplastics are even tinier, measuring less than 1 micrometer—far smaller than the width of a human hair. These pollutants originate from the degradation of larger plastic items over time, as well as from intentionally manufactured products such as cosmetics and cleaning agents. Once released into the environment, micro- and nanoplastics can enter oceans, rivers, and even the air we breathe, posing significant risks to wildlife and human health.

Marine animals often mistake these tiny particles for food, leading to detrimental health effects and introducing microplastics into the food chain. Due to their minuscule size, they are challenging to remove from the environment and can persist for centuries.

Microplastics in Newborns: A New Concern

While it has long been established that microplastics can cross the placenta, the critical question has been whether these particles remain in the body after birth. The research team at Rutgers Health has found that they do, at least in the case of rats. This finding raises serious concerns regarding potential implications for human health.

“Nobody wants plastic in their liver,” stated Phoebe A. Stapleton, an associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the Rutgers Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy and the study’s senior author. “Now that we know it’s there—as well as in other organs—the next step is to understand why and what that means.”

The Study’s Methodology

To investigate the persistence of micro- and nanoplastics post-birth, Stapleton and her team exposed six pregnant rats to aerosolized food-grade plastic powder for ten days. Two weeks after giving birth, they tested two baby rats for MNP exposure. Alarmingly, the same type of plastic that their mothers had inhaled was discovered in the infants’ lungs, liver, and even brain tissue.

Growing Concerns and Implications

These findings contribute to the mounting evidence of potential hazards posed by micro- and nanoplastics. The presence of plastics in food, farmland, seawater, and snow suggests that these omnipresent particles could lead to serious health issues, including cancer, inflammation, and tissue degeneration. Stapleton emphasizes the urgency of this issue, calling for increased research funding to better understand the implications of these pollutants.

“Without answers, we can’t have a policy change,” she added. Enhanced knowledge could enable regulators to implement more stringent regulations regarding plastic usage, ultimately aiming to protect public health.

Broader Ecological Impacts

The study’s results also raise critical questions about the toxicological impacts of MNP exposure on maternal-fetal health and the broader ecosystem. Marine life is unwittingly affected by these pervasive particles, leading to issues such as physical blockages, starvation, and the absorption of toxic chemicals associated with plastics. Research indicates that micro- and nanoplastics may disrupt the reproductive systems of marine species, contributing to systemic toxicity and altering entire ecosystems.

Addressing this global challenge requires urgent attention to reduce plastic pollution and mitigate its harmful impacts on biodiversity.

Looking Ahead

“Eventually, the persistence of these materials in human tissue could lead to greater regulation,” Stapleton noted. “While plastics have undoubtedly improved consumer products, too little is known about their long-term health impacts. As researchers fill knowledge gaps, regulators will be better equipped to protect public health.”

Although the complete eradication of plastics may not be feasible, Stapleton believes that future policies could guide the use of less toxic alternatives.

In conclusion, while plastics have undoubtedly made our lives more convenient, it is crucial to consider the long-term health implications associated with their pollution. The study from Rutgers Health underscores the urgent need for further research and policy changes to protect both human and environmental health in the face of growing microplastic contamination.

The full study can be accessed in the journal Science of the Total Environment.