Barcelona, Spain – A recent study conducted by researchers from EMBL Barcelona has challenged a long-standing hypothesis in developmental biology: that metabolic activity serves as a global modulator of developmental tempo across species. The study, published in Nature Communications, reveals that metabolism selectively influences the segmentation clock rather than controlling the overall pace of developmental processes across all species.

Embryonic development is a finely tuned, synchronized process, with various cellular activities working in harmony to form tissues and organs. However, the speed at which these processes occur differs widely between species. For example, in humans, it takes approximately 60 days for embryonic development to progress to organ formation, while in mice, the same process takes only 15 days.

Miki Ebisuya, Group Leader at EMBL Barcelona, now a professor at the Physics of Life TU Dresden, and her research team embarked on a study to determine whether metabolism plays a role in modulating the tempo of development. Their findings are a significant departure from the previous belief that metabolism might globally control the developmental speed of various processes across species.

For decades, scientists have debated whether metabolism functions as a common regulator of the tempo of biological processes. While earlier studies hinted that metabolic activities could influence processes like the segmentation clock and neurogenesis, the prevailing theory suggested that metabolism might be the overarching modulator of development. However, the findings of Ebisuya’s team show that metabolic activities do not act as a global controller for developmental speed.

“We now believe that the varying tempos of development across species arise from the interplay of multiple factors rather than a single metabolic principle,” said Mitsuhiro Matsuda, Staff Member at TU Dresden and the first author of the study.

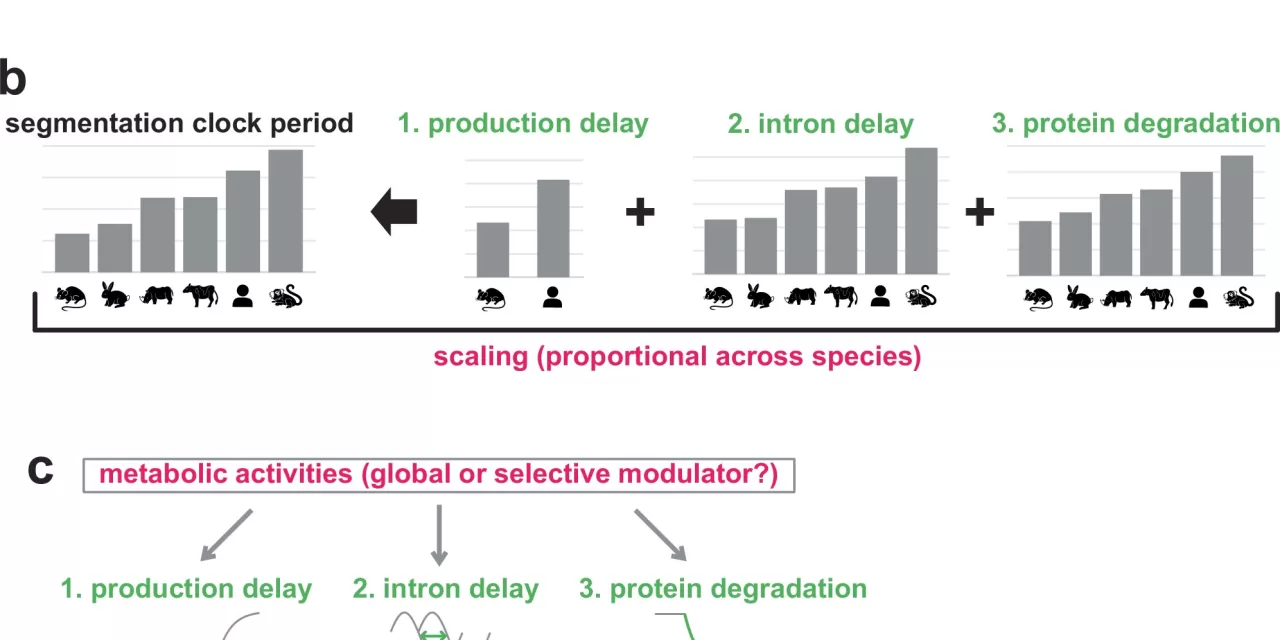

The study focused on the segmentation clock, a mechanism responsible for the rhythmic formation of body segments, which ultimately give rise to vertebrae and ribs. Ebisuya’s team found that metabolic inhibition could selectively impact different aspects of the segmentation clock. When they inhibited glycolysis, the pathway responsible for glucose breakdown, they observed slower degradation and extended production time of a protein called Hes7. However, this did not influence the timing of intron processing, a key step in gene expression. Conversely, inhibiting mitochondrial metabolism affected the intron processing delay but did not change protein degradation or production.

Through these experiments, the researchers discovered that metabolic activity does not universally control all processes within the segmentation clock. Instead, each molecular process within the clock can be modulated independently, with scaling differences observed across species. These differences are more likely the result of evolutionary constraints and multiple selective factors, rather than being driven by one overarching metabolic principle.

“Our findings suggest that developmental tempos are shaped by an intricate combination of metabolic and molecular processes, each fine-tuned by evolutionary pressures specific to each species,” said Ebisuya.

The study marks a significant advancement in understanding the complex relationship between metabolism and development, offering a new perspective on how biological processes are orchestrated during embryogenesis.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are based on research conducted by EMBL Barcelona and its collaborators. The findings should be interpreted within the context of the study and may evolve with future research.