A groundbreaking study published in Science reveals that low sugar intake in utero and during the early years of childhood can meaningfully lower the risk of developing chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes and hypertension in adulthood. This research, conducted by scientists from the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, McGill University, and the University of California, Berkeley, highlights the long-term health effects of reduced sugar consumption in early life.

The study found that children who experienced reduced sugar exposure in the first 1,000 days following conception had up to a 35% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes and a 20% lower risk of hypertension as adults. While limiting sugar intake by the mother prior to birth was beneficial, continued restriction post-birth enhanced the protective effects, offering further health benefits.

A Unique Natural Experiment

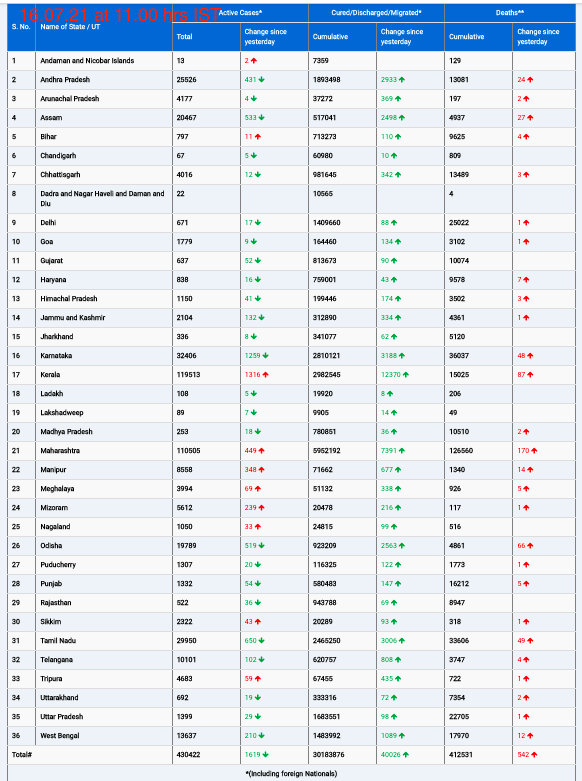

The researchers leveraged an unintended “natural experiment” arising from sugar rationing policies during World War II. Beginning in 1942, the United Kingdom imposed strict limits on sugar as part of wartime food rationing, which ended in 1953. This period provided researchers with a unique opportunity to study the long-term health impacts of early-life sugar exposure—or lack thereof.

Using data from the U.K. Biobank, a large repository of medical and lifestyle information, researchers tracked health outcomes in adults conceived just before and after the end of sugar rationing. Those born into the sugar-scarce conditions prior to 1953 experienced significantly lower sugar exposure compared to those born after rationing ended, who encountered sugar-rich environments. By comparing the health outcomes of these groups, the researchers uncovered the significant protective effects associated with reduced early-life sugar intake.

Lower Disease Risk and Delayed Onset

The study revealed not only a reduced risk of disease but also a delay in the onset of conditions for those who did develop diabetes or hypertension. People who experienced low sugar intake in their first 1,000 days were found to delay the onset of diabetes by an average of four years and hypertension by about two years.

“Studying the long-term effects of added sugar on health is challenging,” said Tadeja Gracner, the study’s lead author and senior economist at the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research. “Our study benefits from a unique historical context that allowed us to examine how early exposure to a low-sugar diet can influence chronic disease risk decades later.”

Lifelong Benefits of Reduced Early-Life Sugar Exposure

With sugar intake nearly doubling after rationing ended—from 8 teaspoons (40 grams) to 16 teaspoons (80 grams) per day—the differences in sugar exposure between the two groups were stark. Even with this increased consumption post-rationing, the period of restricted intake provided enduring health benefits.

Gracner and her colleagues noted that the benefits observed in the rationed group underscore the impact of limiting sugar intake in the crucial early stages of life. “Reducing added sugar early in life is a powerful step towards improving children’s health over their lifetimes,” said study co-author Claire Boone of McGill University and the University of Chicago.

Implications for Public Health Policy

The findings offer critical insights into potential strategies to reduce the prevalence of chronic diseases. Co-author Paul Gertler of UC Berkeley compared early-life sugar exposure to tobacco, advocating for policy changes that could help curb sugar consumption among children. He called for increased accountability among food companies, specifically those producing and marketing sugary foods to young children.

This research marks the beginning of a broader investigation into how early-life nutrition shapes a wide range of adult health outcomes, including cognitive function, chronic inflammation, and economic productivity. Future studies are expected to deepen the understanding of how early-life dietary interventions can lead to healthier, longer lives.

The insights gained from this study underscore the urgent need to rethink dietary guidelines and food marketing practices aimed at children. With chronic diseases like diabetes costing an average of $12,000 per year in the United States alone, and earlier diagnoses shortening life expectancy, early dietary interventions may provide a cost-effective approach to extending quality and length of life for future generations.