Key facts

- An estimated 5.4 million people worldwide are bitten by snakes each year with 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenomings.

- Around 81 410 to 137 880 people die each year because of snake bites, and around three times as many amputations and other permanent disabilities are caused by snakebites annually.

- Bites by venomous snakes can cause paralysis that may prevent breathing, bleeding disorders that can lead to a fatal haemorrhage, irreversible kidney failure and tissue damage that can cause permanent disability and limb amputation.

- Agricultural workers and children are the most affected. Children often suffer more severe effects than adults, due to their smaller body mass.

Overview

Snakebite envenoming is a potentially life-threatening disease that typically results from the injection of a mixture of different toxins (“venom”) following the bite of a venomous snake. Envenoming can also be caused by having venom sprayed into the eyes by certain species of snakes that have the ability to spit venom as a defense measure.

Snake antivenoms are effective treatments to prevent or reverse most of the harmful effects of snakebite envenoming and are included in the WHO list of essential medicines. Most deaths and serious consequences from snake bites are entirely preventable by making safe and effective antivenoms more widely available and accessible, and raising awareness on primary prevention among communities and health workers.

The snake species implicated in serious snakebite injury vary from region to region, a fact that increases the challenge of mitigating the burden of snakebite worldwide. Various species of venomous snakes are present in the Western Pacific with variations between and within countries. This diversity is partly attributable to biodiversity in the region. Throughout the rest of tropical Asia, a similar cohort of culprits occurs, and cobras (Naja ssp.), kraits (Bungarus ssp.) and Russell’s vipers (where they occur) are responsible for the lion’s share of serious bites.

In Papua New Guinea, the taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) is responsible for the most bites, followed by the death adders (Acanthophis spp.). Both groups of snakes occur also in parts of Australia, but bites in that country are very rare. The two major challenges facing snakebite response in the Western Pacific Region include: 1) inadequate mapping of snakebite envenoming; and 2) availability of antivenoms.

Symptoms

Bites or sprayed venom from venomous snakes can cause a range of acute and serious medical emergencies. Envenoming from different types of snakes can cause different symptoms, some more serious than others. This makes the preparation of correct antivenoms an ongoing problem.

Envenoming can cause severe paralysis that may prevent breathing, making immediate medical attention critical. People may also experience bleeding disorders that can lead to fatal hemorrhages or irreversible kidney failure. Severe local tissue destruction may also occur, which can lead to permanent disability and even limb amputation. Children are at higher risk of severe effects due to lower body mass than adults.

Most deaths and serious consequences from snake bites are entirely preventable by making safe and effective antivenoms more widely available and accessible, particularly in high-risk areas. High-quality snake antivenoms are the only effective treatment to prevent or reverse most of the venomous effects of snake bites.

Treatment:

Snake antivenoms are effective treatments to prevent or reverse most of the harmful effects of snakebite envenoming and are included in the WHO list of essential medicines. The availability and accessibility of these antivenoms, along with raising awareness on primary prevention methods among communities and health workers, are the best ways to limit serious consequences and deaths from snakebite envenoming.

After a bite by a snake suspected of being venomous, follow these steps:

- Immediately move away from the area where the bite occurred.

- Remove anything tight from around the bitten part of the body to avoid harm if swelling occurs.

- Reassure the victim, as most venomous snake bites do not cause immediate death.

- Immobilize the person completely and transport the person to a health facility as soon as possible

- Applying pressure at the bite site with a pressure pad may be suitable in some cases.

- Avoid traditional first aid methods or herbal medicines.

- Paracetamol may be given for local pain (which can be severe).

- Vomiting may occur, so place the person on their left side in the recovery position.

- Closely monitor airway and breathing and be ready to resuscitate if necessary.

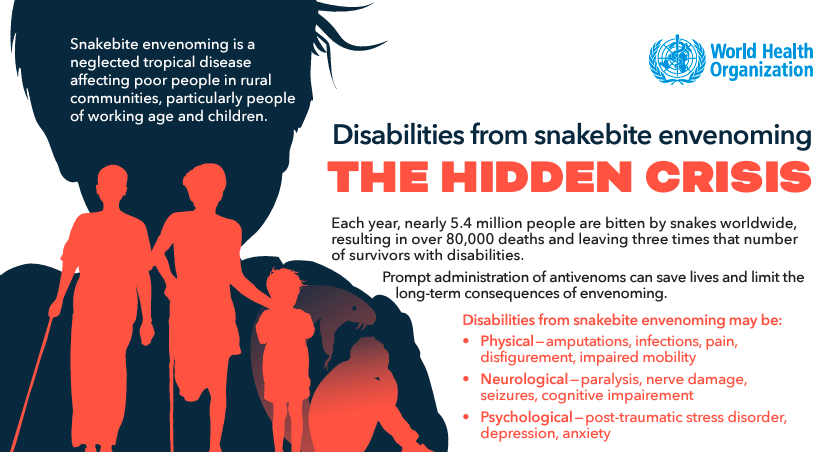

Disabilities from snakebite envenoming: The Hidden Crisis

Snakebite envenoming is a neglected tropical disease affecting poor people in rural communities, particularly people of working age and children. Each year, nearly 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes worldwide, resulting in over 80,000 deaths and leaving three times that number of survivors with disabilities. Prompt administration of antivenoms can save lives and limit the long-term consequences of envenoming.

The theme this year is Disabilities from snakebite envenoming. Disabilities from snakebite envenoming may be:

- Physical — amputations, infections, pain, disfigurement, impaired mobility

- Neurological — paralysis, nerve damage, seizures, cognitive impairment

- Psychological — post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety

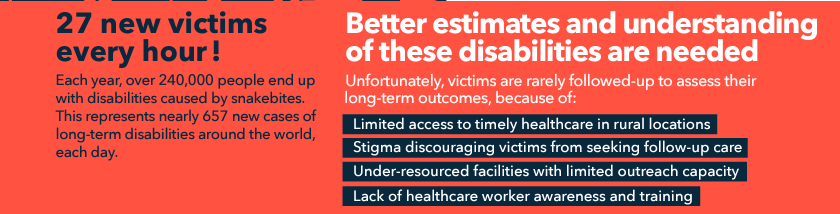

Disabilities from snakebite envenoming is severely underreported.

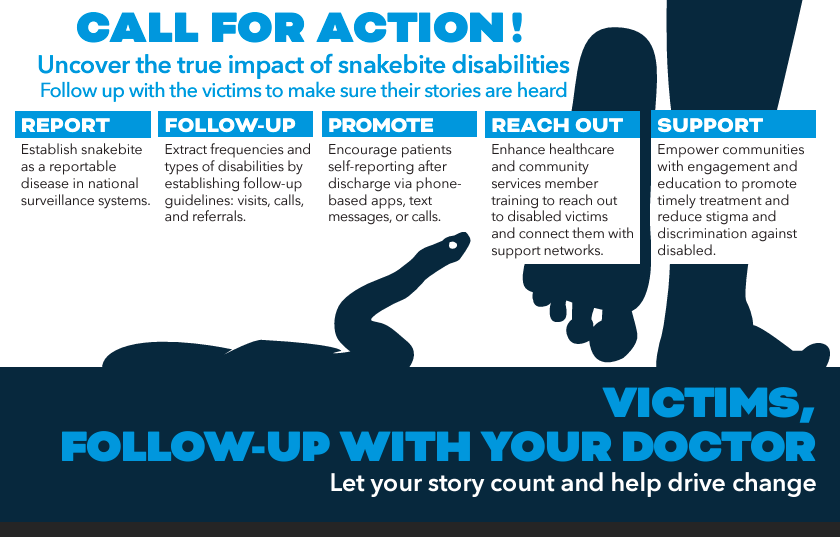

It is time to call for action to have better estimates and understanding of these disabilities to uncover the true impact of snakebite disabilities and follow up with the victims to make sure their stories are heard.

Challenges producing antivenoms

A significant challenge in manufacturing of antivenoms is the preparation of the correct immunogens (snake venoms). At present very few countries have capacity to produce snake venoms of adequate quality for antivenom manufacture, and many manufacturers rely on common commercial sources. These may not properly reflect the geographical variation that occurs in the venoms of some widespread species. In addition, lack of regulatory capacity for the control of antivenoms in countries with significant snake bite problems results in an inability to assess the quality and appropriateness of the antivenoms.

A combination of factors has led to the present crisis. Poor data on the number and type of snake bites have led to difficulty in estimating needs, and deficient distribution policies have further contributed to manufacturers reducing or stopping production or increasing the prices of antivenoms. Weak regulation and the marketing of inappropriate or poor quality antivenoms has also resulted in a loss of confidence in some of the available antivenoms by clinicians, health managers and patients, which has further eroded demand.

Weak health systems and lack of data

A combination of strategic and risk-based placement of antivenoms, suitable healthcare staff training, availability of affordable, safe and effective antivenoms and equipment, along with the promotion of responsible health-seeking behaviours, can lead better outcomes for snakebite patients and a considerable reduction in the impact of snakebite-related morbidity and mortality. However, the combination of poor geographical access to and inadequate health services in remote communities hinders the chance of receiving appropriate treatment.

Health systems in many countries where snake bites are common often lack the infrastructure and resources to collect robust statistical data on the problem. Assessing the true impact is further complicated by the fact that cases reported to health ministries by clinics and hospitals are often only a small proportion of the actual burden because many victims never reach primary care facilities and are therefore unreported. This is contributed to by socio-economic and cultural factors that influence treatment-seeking behaviour with many victims opting for traditional practices rather than hospital care.

Under-reporting of snake bite incidence and mortality is common. In Nepal, for example, where 90% of the population lives in rural areas, the Ministry of Health reported 480 snake bites resulting in 22 deaths for the year 2000 yet figures for the same year collected in a community-based study of one region (eastern Nepal) detailed 4078 bites and 396 deaths (1). Likewise, a very large community level study of snakebite deaths in India gave a direct estimate of 45 900 (99% CI: 40 900–50 900) deaths in 2005, which is over 30 times higher than the Government of India’s official figure (2). Revised estimates based on verbal autopsies and other data now suggest that as many as 1.2 million Indians died from snakebite envenoming between 2000–2019 (average of 58 000/year) (3). A comparison of hospital-registered deaths in one district of Sri Lanka to data from the Registrar-General’s office on deaths demonstrated that 62.5% of deaths from snakebite envenoming were not reported in hospital data (4).

In situations where data on snakebite envenoming are poor, it is difficult to accurately determine the need for antivenoms. This leads to under-estimation of antivenom needs by national health authorities driving down demand for manufacturers to produce antivenom products, and for some, their departure from the market. The weaknesses in some regulatory systems that leads to licensing of ineffective or incorrect products is sometimes coupled to poor procurement practices and inefficient distribution strategies, further hindering access to antivenoms and creating shortages of safe, affordable and effective products.

Low production of antivenoms

Given low demand, several manufacturers have ceased production, and the price of some antivenom products have dramatically increased in the last 20 years, making treatment unaffordable for the majority of those who need it. Rising prices also further suppress demand, to the extent that antivenom availability has declined significantly or even disappeared in some areas. The entry into some markets of inappropriate, untested, or even fake antivenom products has also undermined confidence in antivenom therapy generally.

Many believe that unless strong and decisive action is taken quickly, antivenom supply failure is imminent in Africa and in some countries in Asia.