February 18, 2025 | Stanford, CA – A groundbreaking study by Stanford researchers has pinpointed 380 inherited genetic variants that significantly contribute to the risk of developing various cancers. For years, scientists have known that certain single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the human genome are associated with an increased risk of cancer, but the exact role these variants play in driving uncontrolled cellular growth has remained unclear. Now, researchers have undertaken the first large-scale screening of these inherited genetic changes and have identified those that are critical for initiating cancer development.

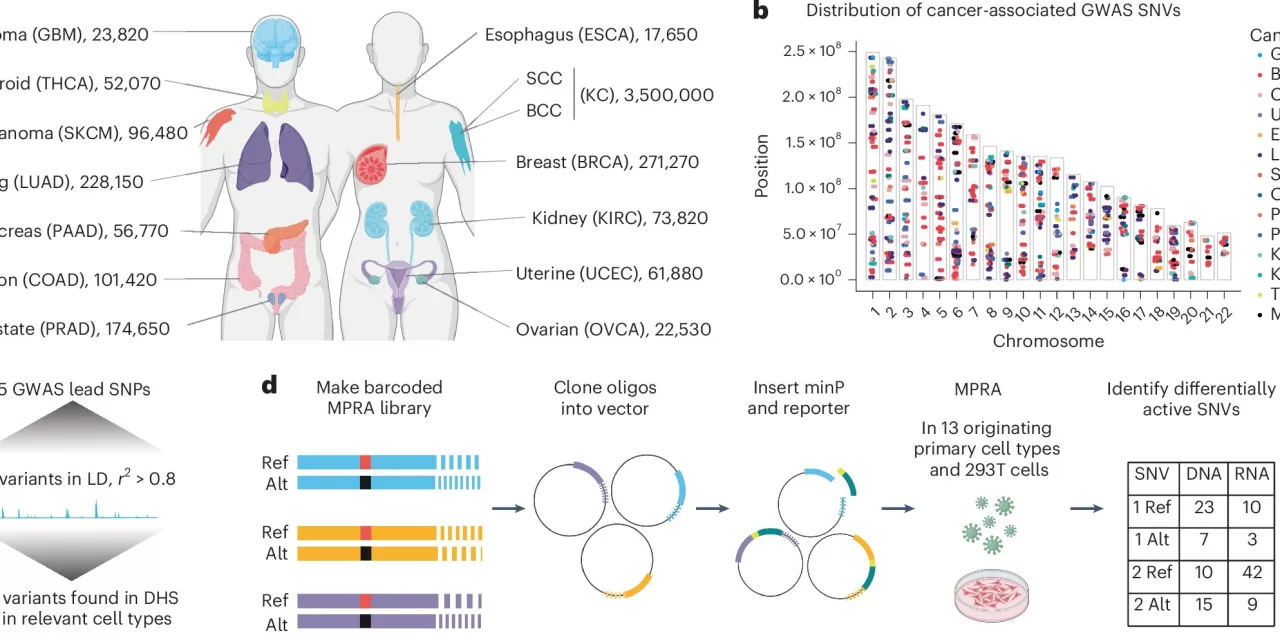

The study, led by Dr. Paul Khavari, Professor and Chair of Dermatology at Stanford Medicine, focuses on the germline genome, which consists of the DNA inherited from one’s parents. By studying the DNA of millions of people diagnosed with the 13 most common cancer types—representing over 90% of all human malignancies—the research team homed in on nearly 400 variants that are crucial to the expression of genes involved in cancer development.

The research, published in Nature Genetics, marks a significant advance in understanding cancer risk. Dr. Khavari, the senior author of the study, emphasized the potential impact of this work on genetic screening and cancer prevention. “Certain variants, if inherited from your parents, can substantially increase your risk of developing many types of cancer,” Khavari said.

The researchers found that these variants are located in regulatory regions of DNA, rather than in the “coding” regions that directly instruct cells to produce proteins. These regulatory regions control the activity of nearby or even distant genes, influencing cellular processes such as DNA repair, energy production, and cell movement within the tissue microenvironment. These processes are all key players in cancer growth and metastasis.

The study also uncovered new insights into the role of inflammation in cancer development. Previously, the connection between inflammation and cancer was acknowledged, but the cause remained unclear. This new research suggests that inflammation in cancer may not only be driven by the cancer cells themselves but also by the immune system, opening new avenues for therapeutic strategies.

In a particularly exciting finding, the researchers discovered that half of the identified variants are required to sustain cancer growth in laboratory-grown cancer cells. The implications of this discovery are far-reaching, offering hope for new cancer therapies aimed at targeting these regulatory regions.

In addition to its potential for guiding future cancer treatments, this research is expected to improve genetic screening programs aimed at assessing an individual’s cancer risk. Over time, this could lead to more personalized health plans, enabling better prevention and earlier detection of cancer.

Dr. Laura Kellman, the lead author of the study and a former graduate student of Dr. Khavari, pointed out that the newly identified variants could help develop individualized risk assessments for many genetically complex diseases, including cancer. “We expect this to be incorporated into genetic screening tests over the next decade, providing critical insights into who is at risk for various cancers and allowing for targeted interventions,” Kellman explained.

This discovery opens the door to new approaches for cancer prevention, treatment, and personalized medicine, with the potential to save countless lives in the coming years.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions presented in this article are based on research published in Nature Genetics. These findings are subject to further validation and may not immediately translate into clinical practice.

More information on this study can be found in the paper: Kellman, L. N., et al., “Functional analysis of cancer-associated germline risk variants,” Nature Genetics, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41588-024-02070-5.