Breakthrough in Malaria Research

A significant breakthrough in malaria research has been made, bringing scientists one step closer to developing a safe and effective live vaccine. Researchers have identified a gene in the malaria parasite that could pave the way for improved immunization. The study, published in PLOS One, highlights a novel approach that could revolutionize malaria prevention.

Malaria remains one of the deadliest diseases in human history, responsible for over 400,000 deaths annually and infecting more than 200 million people each year. While measures such as insecticide-treated nets and walls help in controlling the spread, an effective long-term vaccine is essential for permanent eradication.

A Novel Approach to Immunization

Current malaria vaccines target a single parasite protein, providing limited and short-lived immunity. The most effective vaccine currently available only offers protection to 70% of vaccinated individuals, with immunity waning after a year without booster doses.

To address this limitation, a team led by biologist Volker Heussler at the University of Bern has explored a new strategy: using a weakened, genetically modified malaria parasite as a vaccine. Unlike previous attempts that relied on radiation to weaken the parasite, this method employs targeted genetic modifications to halt its development before it reaches the bloodstream.

Targeting the Liver Stage

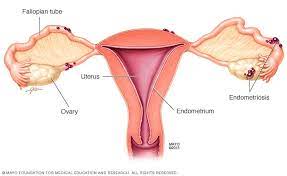

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has a complex life cycle. After entering the bloodstream through a mosquito bite, it rapidly travels to the liver, where it multiplies over several days before invading red blood cells and causing severe illness.

Using large-scale genetic screening, researchers identified a gene whose loss stops the parasite’s development in the liver phase without killing it. They tested 1,500 parasite variants in mice and discovered one with the required characteristics: it reached the liver but did not progress to the bloodstream.

Addressing the Risk of Breakthrough Infections

A major concern with a live vaccine is the risk of the parasite breaking through and causing malaria. To prevent this, the researchers took an extra precaution by knocking out a second gene, previously identified by a U.S. research team, further blocking its ability to progress.

Initial trials with the double-attenuated parasite in mice have shown promising results. The vaccinated mice remained fully protected against malaria without any adverse effects, even at high doses. However, further research is needed to confirm whether these results can be replicated in humans.

The Road Ahead

While this discovery marks a significant advancement, Heussler cautions that a fully safe and effective human vaccine is still a long way off. Further modifications, such as a potential triple gene knockout, may be necessary to ensure the vaccine is completely reliable. If breakthrough infections were to occur, the vaccine could be deemed unsafe for human use.

As researchers continue to refine their approach, this discovery offers new hope in the global fight against malaria. The potential for a genetically weakened parasite vaccine could be a game-changer in eliminating one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Further research and clinical trials are necessary before an effective malaria vaccine becomes available for human use.