BASEL, SWITZERLAND – The placebo effect, where patients improve after receiving an inert treatment simply because they believe it’s real, has long been a perplexing aspect of medicine. Traditionally reliant on deception, a growing field of research is exploring “open-label placebos,” where patients know they are receiving an inactive substance. Surprisingly, these can still yield positive results. Now, a new study suggests that explaining to patients why a placebo might work significantly enhances its beneficial effects.

The research, published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, focused on alleviating premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a common condition marked by moodiness, fatigue, and irritability. Scientists have observed that placebos often account for a significant portion (around 40%) of the benefits seen in PMS treatment trials. Given that common treatments like antidepressants (SSRIs) and hormonal birth control can have side effects, researchers are exploring alternatives.

Led by Dr. Antje Frey Nascimento, a professor of psychology at the University of Basel, the study involved 150 participants experiencing PMS. They were divided into three groups: one received no treatment beyond their usual routines (excluding psychopharmacological drugs), another received placebo pills with no explanation, and the third received placebo pills along with a detailed, 15-minute explanation.

This explanation covered the known power of placebo effects, their prevalence in PMS, how they might work “automatically,” and the concept of conditioning – associating pill-taking with symptom relief since childhood.

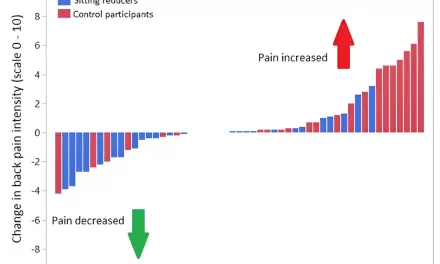

Participants tracked their PMS symptoms over three menstrual cycles. The results were striking. Those who received the placebo with the explanation reported a 79.3% reduction in symptom intensity and an 82.5% decrease in how symptoms interfered with their daily lives. In contrast, the group receiving the placebo without explanation saw reductions of 50.4% and 50.3%, respectively. The no-treatment group also showed improvement (33% intensity reduction, 45.7% interference reduction), possibly due to increased self-monitoring via symptom diaries or the Hawthorne effect (changing behavior when observed), according to Dr. Nascimento. However, the group receiving the explained placebo experienced significantly greater relief than the other two groups.

“We picked PMS because it’s really prevalent and it’s really understudied,” Dr. Nascimento stated, highlighting the potential of a side-effect-free approach.

Experts not involved in the study note the importance of understanding the mechanisms behind open-label placebos. Dr. Luana Colloca, a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, who studies pain and placebos, explained that research shows placebos can trigger measurable brain changes, including reduced pain activity and increased release of dopamine and opioids, chemicals associated with reward and comfort.

While deceptive placebos have often been seen as a complication in clinical trials, especially for pain medication, the study of open-label placebos is relatively new. Early research dates back to 1965, but modern interest surged after studies in 2008 (ADHD) and 2010 (Irritable Bowel Syndrome, IBS). Notably, the IBS study also provided patients with an explanation about the “mind-body self-healing processes” triggered by placebos. Dr. Nascimento’s study is among the first to specifically isolate the importance of this explanatory component.

“In reality, we still don’t know why the act of taking a pill, even if you don’t believe in the medication’s therapeutic effect, can trigger a benefit,” said Dr. Colloca. “So I love this study because they try to understand the mechanisms… the rationale can help to somehow maintain an expectation of relief.”

Open-label placebos have shown promise for conditions ranging from pain and cancer-related fatigue to allergies, depression, and hot flashes. However, integrating them into standard clinical practice faces hurdles. “We are still far away from having a mechanism to introduce this in clinical practice,” Dr. Colloca noted, particularly in the United States, suggesting engagement with regulatory bodies like the FDA is needed. In contrast, she mentioned that placebos are available over-the-counter in pharmacies in Germany.

The findings raise compelling questions about treatment paradigms. As Dr. Colloca pondered regarding PMS, “If women improve with placebo, why do we need to expose them to medications that can somehow have side effects?” This research suggests that honesty, coupled with a clear explanation of the body’s potential self-healing mechanisms, could be a powerful, non-pharmacological tool in healthcare.

Disclaimer: This news article is based on information from a specific study published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine and related expert commentary concerning open-label placebos. It is intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions about your treatment or medication.