Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have achieved a groundbreaking success in the fight against prion disease, a fatal neurodegenerative condition. A team led by Sonia Vallabh, Eric Minikel, and David Liu has developed a gene-editing treatment that extends the lifespan of mice infected with prion disease by an impressive 50%. This treatment, which utilizes base editing technology, works by making a single-letter change in the DNA, leading to a reduction of the prion protein levels in the brain by as much as 60%.

Prion diseases, which include fatal familial insomnia and mad cow disease, currently have no cure. The new gene-editing approach offers hope for developing treatments that could not only slow the progression of the disease but potentially prevent it in patients who have already developed symptoms. The study, published in Nature Medicine, marks a significant step toward a one-time treatment for all prion disease patients, regardless of the genetic mutation responsible for their condition.

Vallabh, who is a patient scientist with a personal connection to the disease, noted the significance of this breakthrough. “When I received my genetic test report in 2011, the world had never heard of base editing. It’s a huge privilege to have the opportunity to point these powerful new tools at our disease,” she said. Minikel, her husband and collaborator, shared his excitement about the project, remarking on the incredible opportunity to merge disease models with cutting-edge gene-editing technology.

David Liu, who co-led the research, expressed optimism about the results, stating, “We are hopeful the results might inform the future development of a one-time treatment for this important class of diseases.” The project also had the support of graduate students Meirui An and Jessie Davis, who contributed significantly to the study.

Prion diseases can arise from genetic mutations, spontaneous occurrences, or infections, and researchers believe that the base-editing approach could apply to all forms of these conditions. “This has the potential to be a really promising strategy,” said An, a co-author of the study.

Vallabh and Minikel have been researching prion disease since 2012, driven by Vallabh’s personal experience of losing her mother to fatal familial insomnia. Their work, initially inspired by the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing in 2013, evolved when Liu’s lab developed base editing technology in 2018. This new method allows precise changes to DNA at the single-letter level and has the potential to correct the prion protein levels without causing harmful side effects.

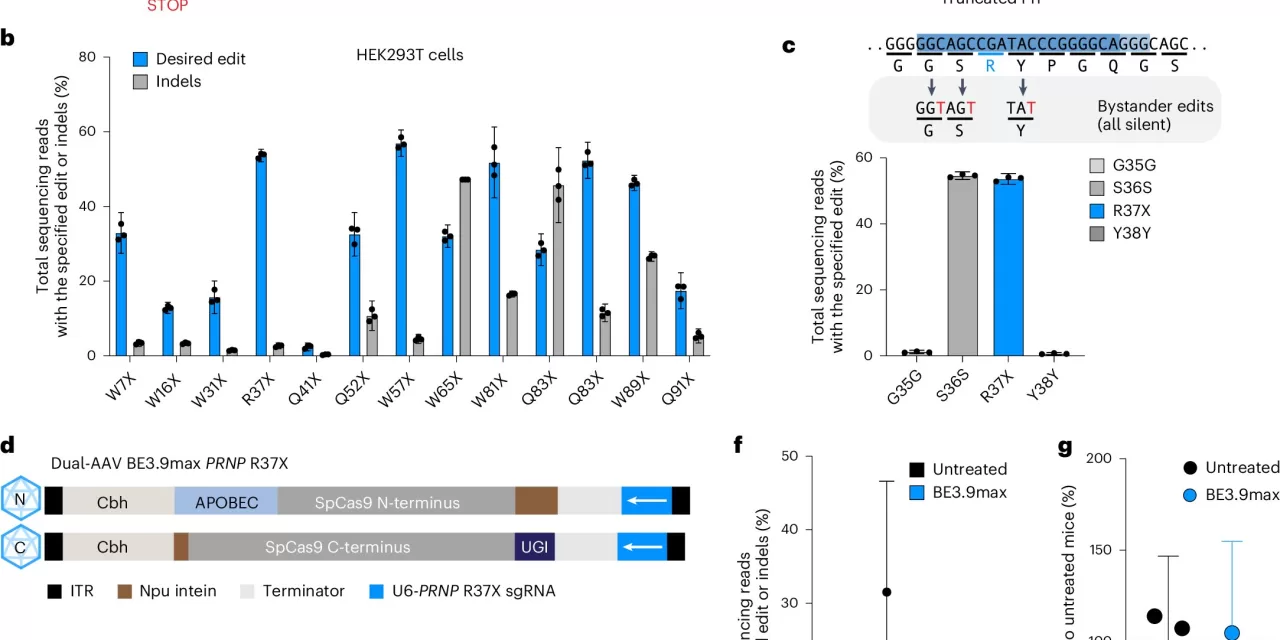

In their study, the researchers used base editing to install the R37X mutation, a naturally occurring genetic variation that reduces prion protein production without adverse effects in humans. The team then delivered the base-editing tools to the mice’s brains via adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). The results were striking: prion protein levels were reduced by 50%, and the treated mice lived 50% longer than untreated ones.

Future improvements are planned, including the development of smaller base-editing cargo to reduce costs and the exploration of prime editing for more complex DNA changes. While the treatment is still in its early stages, the success in animal models has researchers optimistic that a viable therapy could be developed in the future.

“This is a promising step forward, but we know there’s still a long way to go to make this a widely available therapy,” Minikel added. However, the breakthrough has already demonstrated the potential of gene-editing technologies in tackling one of the most challenging and rare diseases affecting the brain.

For more details on the study, refer to: Meirui An et al, In vivo base editing extends lifespan of a humanized mouse model of prion disease, Nature Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03466-w.

This exciting development raises the hope of future treatments for prion diseases, offering renewed optimism for patients and families affected by these devastating conditions.