A groundbreaking study conducted by researchers from UC Berkeley has unveiled the presence of toxic metals such as lead, arsenic, and cadmium in tampons, a product used monthly by millions of people worldwide. The findings, published in the journal Environment International, highlight significant public health concerns.

Tampons are particularly worrying as potential sources of chemical exposure due to the high absorption capacity of the vaginal skin compared to other body parts. With 50-80% of menstruating individuals using tampons regularly, the implications are far-reaching. Lead author Jenni A. Shearston, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health and the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, & Management, emphasized the novelty and importance of the research, stating, “To our knowledge, this is the first paper to measure metals in tampons. Concerningly, we found concentrations of all metals we tested for, including toxic metals like arsenic and lead.”

The study points out the severe health risks associated with these metals, including increased risks of dementia, infertility, diabetes, cancer, and damage to critical organs and systems. Kathrin Schilling, assistant professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and co-author of the study, underscored the pervasive nature of metal exposure, highlighting the heightened risk for women using these products.

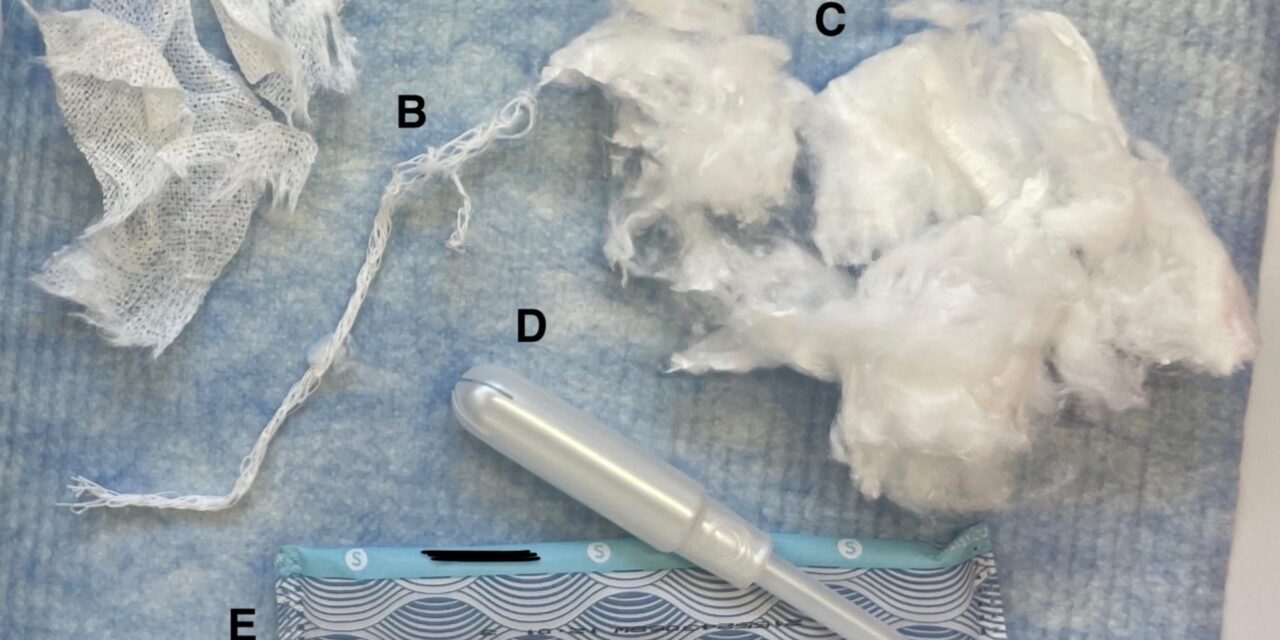

Researchers analyzed 30 tampons from 14 different brands, testing for 16 metals: arsenic, barium, calcium, cadmium, cobalt, chromium, copper, iron, manganese, mercury, nickel, lead, selenium, strontium, vanadium, and zinc. The study found metals present in all tampon types, with significant variability depending on factors such as purchase location (US vs. EU/UK), organic vs. non-organic, and store- vs. name-brand. Notably, non-organic tampons showed higher lead concentrations, whereas organic tampons had higher arsenic levels.

The source of these metals in tampons is multifaceted. Potential contamination routes include the absorption of metals by cotton from water, air, soil, or nearby pollutants, such as a lead smelter near a cotton field. Additionally, metals might be intentionally added during manufacturing processes as pigments, whiteners, antibacterial agents, or other factory processes.

Shearston hopes the findings will prompt regulatory action and greater public awareness. “I really hope that manufacturers are required to test their products for metals, especially for toxic metals,” she said. “It would be exciting to see the public call for this, or to ask for better labeling on tampons and other menstrual products.”

While the immediate health implications remain uncertain, future research will focus on how much of these metals can leach from tampons and be absorbed by the body, as well as the presence of other potentially harmful chemicals in these products.

For more information, refer to the full study: Jenni A. Shearston et al, “Tampons as a source of exposure to metal(loid)s,” Environment International (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108849.