A groundbreaking experimental malaria vaccine has shown significant promise in protecting pregnant women from the life-threatening disease, according to new research from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). This development could mark a pivotal advancement in the fight against malaria, particularly in Africa, where the disease is a leading cause of maternal and infant mortality.

Malaria, caused by parasites from the species Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) and transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, remains a grave threat to pregnant women, infants, and young children. Each year, an estimated 50,000 maternal deaths and 200,000 stillbirths in Africa are attributed to malarial parasitemia during pregnancy, underscoring the urgent need for effective preventive measures.

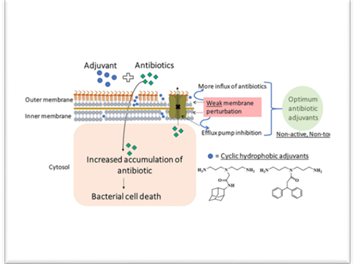

The NIH-led trials focused on the PfSPZ vaccine, a novel radiation-attenuated vaccine based on Pf sporozoites—a stage in the parasite’s lifecycle. Developed by US-based biotechnology company Sanaria, the vaccine has demonstrated remarkable efficiency and does not require a booster dose, a first for any malaria vaccine.

One of the key trials enrolled 300 healthy women aged 18 to 38 who anticipated becoming pregnant shortly after immunization. These participants were treated to eliminate existing malaria parasites before receiving three injections of either a saline placebo or the investigational vaccine at one of two dosages, spaced over a month.

The results were compelling. Women who received the PfSPZ vaccine at either dosage level experienced a significant degree of protection from parasite infection and clinical malaria that lasted for two years, even without a booster dose. The researchers, from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies, Bamako (USTTB) in Mali, co-led the trials.

The findings, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, revealed that among the 55 women who became pregnant within 24 weeks of receiving the third vaccine dose, vaccine efficacy against parasitemia (whether before or during pregnancy) was 65% in those who received the lower dose vaccine and 86% in those who received the higher dose.

Across both study years, among 155 women who became pregnant, vaccine efficacy was 57% for those who received the lower dose and 49% for those in the higher dosage group. Interestingly, women who received the vaccine at either dosage conceived sooner than those who received a placebo, although this result did not reach statistical significance.

The researchers suggest that the PfSPZ vaccine may also reduce the risk of malaria-related early pregnancy losses, given the observed reduction in parasitemia risk during the periconception period by 65% to 86%.

“If confirmed through additional clinical trials, the approach modeled in this study could open improved ways to prevent malaria in pregnancy,” the researchers noted.

This promising development offers new hope in the battle against malaria, potentially safeguarding the lives of thousands of mothers and their unborn children in malaria-endemic regions.