In a groundbreaking study, researchers at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences have discovered a potential link between financial vulnerability and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. The study, led by Duke Han, professor of psychology and family medicine, reveals that those who are more susceptible to financial scams may also have changes in the brain that are often associated with the onset of Alzheimer’s.

With nearly 7 million Americans currently living with Alzheimer’s, the fifth leading cause of death for those 65 and older, the study offers new insight into the early detection of the disease. Alzheimer’s, which will cost an estimated $360 billion in health care this year, often progresses silently in its early stages, making early diagnosis critical for managing the disease.

Brain Changes and Financial Vulnerability

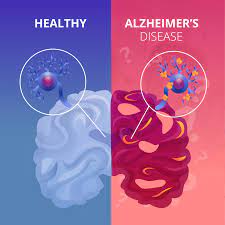

The study involved 97 participants between the ages of 52 and 83, none of whom showed signs of cognitive impairment. Using high-powered MRI, researchers examined the thickness of the entorhinal cortex, a region of the brain that connects the hippocampus (responsible for memory) and the medial prefrontal cortex (which regulates emotion and decision-making). This area is often the first to show signs of thinning in individuals with Alzheimer’s.

Researchers also used the Perceived Financial Exploitation Vulnerability Scale (PFVS) to assess participants’ susceptibility to financial scams, or “financial exploitation vulnerability” (FEV). The findings were significant: older adults with a thinner entorhinal cortex were more likely to exhibit greater financial vulnerability, particularly those aged 70 and above.

“This study provides crucial evidence that financial vulnerability in older adults may be an early indicator of cognitive decline, including Alzheimer’s disease,” said Han, who holds a joint appointment at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. He emphasized that financial vulnerability could be a valuable tool for identifying those at risk of Alzheimer’s, even before clinical symptoms of cognitive impairment appear.

Implications and Limitations

The results, while promising, do not establish a definitive cause-and-effect relationship between financial vulnerability and Alzheimer’s disease. “Financial vulnerability alone isn’t a definitive indicator of cognitive decline,” Han explained. “However, when combined with other factors, it could contribute to a broader risk profile.”

The study’s limitations include a lack of diversity among participants, who were predominantly older, white, and highly educated women. Additionally, the research did not directly measure the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, such as amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which are hallmarks of the disease.

Han stressed the need for further research, particularly long-term studies involving diverse populations, to validate the link between financial vulnerability and cognitive decline. “More research is essential before financial exploitation vulnerability can be relied upon as a clinical tool for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease,” he said.

A New Avenue for Early Detection

As Alzheimer’s continues to affect millions worldwide, early detection remains a top priority for researchers and healthcare providers. Financial vulnerability, often seen as a social or economic issue, may now play a role in the medical understanding of cognitive decline.

The potential to use FEV as part of a cognitive risk assessment could help families and caregivers identify early signs of Alzheimer’s, improving outcomes by enabling earlier intervention. Though more research is needed, this study opens the door to a new avenue of early detection in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease.