A recent study published in Science of the Total Environment has revealed a concerning long-term impact of air pollution on maternal mental health. Women exposed to higher levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) or inhalable particulate matter (PM10) during the second trimester of pregnancy face a nearly fourfold increased risk of postpartum depression, a risk that persists for at least three years.

The research, led by Tracy Bastain, Ph.D., an associate professor of clinical population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, highlights a novel aspect of the study by extending the examination of postpartum depression beyond the first year. “What’s really novel about this work is that we were able to extend the examination of depression beyond the first year postpartum, and have shown the sustained effect of air pollution during pregnancy on symptoms of depression all the way through three years postpartum,” said Bastain.

Nitrogen dioxide, a byproduct of fossil fuel combustion in vehicles and power plants, and particulate matter (PM10), which includes particles smaller than 10 micrometers from sources such as dust, pollen, and industrial pollutants, are both known to contribute to a range of health problems. This study adds a significant layer to this knowledge by linking these pollutants to prolonged postpartum depression.

The longitudinal study followed 361 mothers from pregnancy through three years postpartum, assessing depressive symptoms at one, two, and three years after childbirth. Researchers compared these symptoms with air pollution data from the participants’ residential areas during pregnancy. They found a robust connection between elevated pollution levels and increased depressive symptoms.

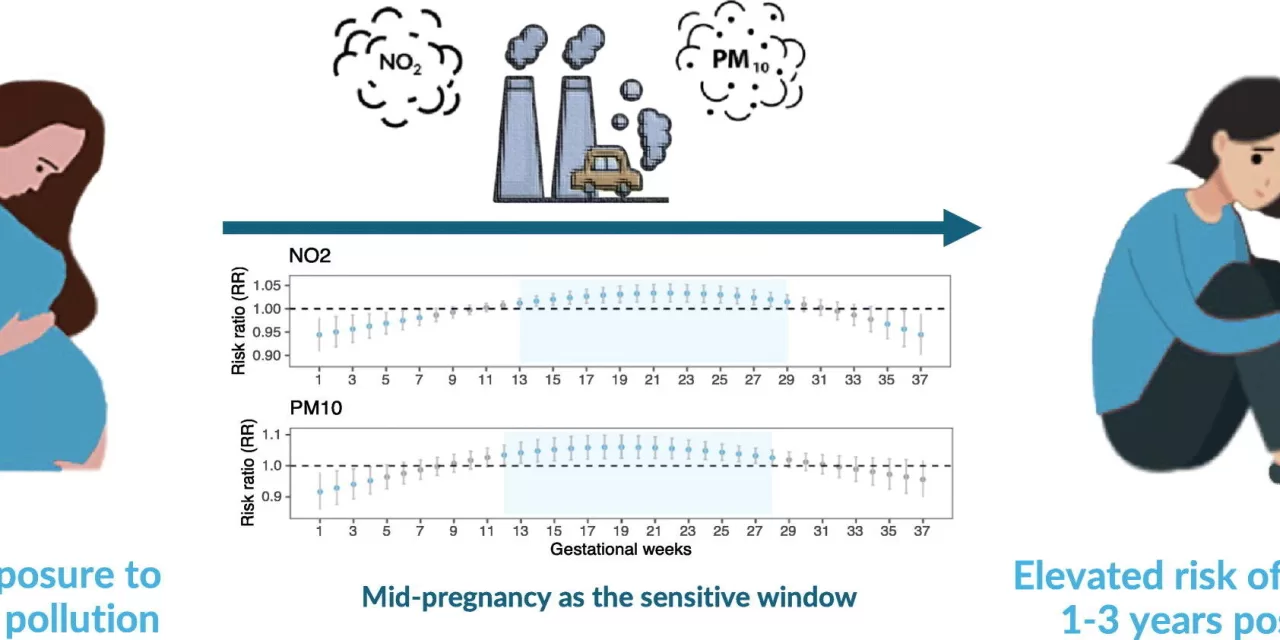

Women exposed to higher NO2 levels during weeks 13 to 29 of pregnancy had a 3.86 times higher risk of postpartum depression for up to three years. Similarly, higher PM10 exposure during weeks 12 to 28 was associated with a 3.88 times increased risk. Notably, the study reported that 17.8% of women experienced depressive symptoms after one year, 17.5% after two years, and 13.4% after three years.

“This study found a higher percentage of clinically significant depression compared to recent CDC data, suggesting that postpartum depression may be more prevalent than current national estimates indicate,” Bastain noted.

The findings underscore the importance of ongoing mental health screening beyond the traditional 12-month postpartum period and suggest that reducing air pollution exposure during the second trimester could help mitigate the risk of postpartum depression. Bastain advises pregnant women to limit outdoor exercise during high pollution periods, such as rush hours or wildfire events, and to stay indoors during peak heat times when pollution levels are high.

Looking ahead, Bastain and her team at the MADRES Center for Environmental Health Disparities plan to continue exploring the long-term effects of air pollution and chemical exposures on maternal and child health. “We’re continuing to drive this research forward so we can help protect the health of mothers and children for the long term,” she said.

For further reading, see: Yuhong Hu et al., Prenatal exposure to ambient air pollution and persistent postpartum depression, Science of The Total Environment (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176089.