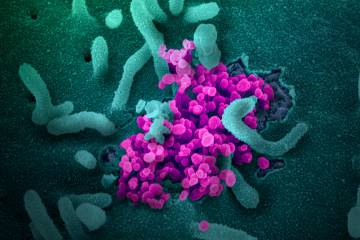

CREDIT:WILL KIRK / JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

Findings from Johns Hopkins–led study support antibody-rich blood as an early treatment option

Michael E. Newman and Barbara Benham

The results of a nationwide, multicenter clinical trial led by Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health provide solid evidence for the use of plasma from convalescent patients—those who have recovered from the disease and whose blood contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19—as an early treatment. In a study released Dec. 21, the researchers showed that convalescent plasma reduced the need for hospitalization by half for outpatients with COVID-19 who participated in the study.

“As the changing, often unpredictable landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic demands multiple treatment options—especially in low- and middle-income nations where frontline therapies, such as vaccines and monoclonal antibodies, may not be readily available—our study provides solid evidence that antibody-rich convalescent plasma should be part of the outpatient arsenal,” says study co-lead author David Sullivan, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health with a joint appointment in infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

In the outpatient early treatment study conducted between June 2020 and October 2021, the researchers provided 1,181 randomized patients with one dose each of either polyclonal high-titer convalescent plasma (containing a concentrated mixture of antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2) or placebo control plasma (with no SARS-CoV-2 antibodies). The patients were 18 and older and had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 within eight days prior to transfusion. A successful therapy was defined as a patient not requiring hospitalization within 28 days after plasma transfusion.

The study found that 17 patients out of 592 (2.9%) who received the convalescent plasma required hospitalization within 28 days of their transfusion, while 37 out of 589 (6.3%) who received placebo control plasma did. This translated to a relative risk reduction for hospitalization of 54%.

“With early administration of high-titer SARS-CoV-2 convalescent plasma reducing outpatient hospitalizations by more than 50%, our findings suggest that this is another effective treatment for COVID-19 with the advantages being low cost, wide availability, and rapid resilience to the evolving SARS-CoV-2,” says study co-lead author Kelly Gebo, professor of medicine at the School of Medicine.

“Therefore, we believe that the best role for COVID-19 high-titer convalescent plasma is extending its use to early outpatient treatment when other therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies or drugs, are either not readily available—as in low- and middle-income countries— or ineffective, as with SARS-CoV-2 variants that are resistant to certain monoclonal antibodies,” she says.

Sullivan adds that convalescent plasma is the only antibody therapy that “keeps up with SARS-CoV-2 variants,” including the delta and omicron strains currently spreading around the world, because each patient who recovers from variant COVID-19 produces antibodies that neutralize that specific virus.

Convalescent plasma therapy is currently available in the United States under Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization. Before it can be considered as an early COVID-19 treatment option for outpatients, the FDA must extend the current authorization to include its use in that role.

“We have shared our findings with the FDA, as well as with the World Health Organization,” Sullivan says. “We hope that both organizations will see the value of convalescent plasma for outpatients based on the strength of our study, the largest randomized clinical trial of its kind to date.”

“Eventually, we hope that our data will guide clinicians in how to effectively use high-titer convalescent plasma as an early outpatient treatment, especially regarding timing and dosage,” Gebo says.

Along with Sullivan and Gebo, the members of the study team from Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health were study senior author Daniel Hanley, Lawrence Appel, Sheriza Baksh, Evan Bloch, Arturo Casadevall, Stephan Ehrhardt, Amy Gawad, Laura Hammitt, Douglas Jabs, Nicki Karlen, Sabra Klein, Karen Lane, Bryan Lau, Christi Marshall, Nichol McBee, Andrew Pekosz, David Shade, Shmuel Shoham, Catherine Sutcliffe, Aaron Tobian, and Anusha Yarava.

The other institutions and organizations participating in the study were Ascada Research, Baylor College of Medicine, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Luminis Health, Mayo Clinic, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, National Institutes of Health, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Nuvance Health, Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences, Rhode Island Hospital, The Bliss Group, The Next Practice, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of California Irvine College of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, University of Texas McGovern Medical School at Houston, University of Utah Health and Wayne State University School of Medicine.

The study was principally funded by the U.S. Department of Defense Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense, in collaboration with the Defense Health Agency. Initial support was received from the Bloomberg Philanthropies and the state of Maryland, with additional support coming from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the agency’s Division of Intramural Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the Mental Wellness Foundation, the Moriah Fund, Octapharma Plasma, the Healthnetwork Foundation, and the Shear Family Foundation.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology