Adelaide, Australia – A groundbreaking study by Flinders University researchers suggests that playing in the dirt at childcare centers might be a crucial way for children to enhance their immune systems and gut health. The investigation, which assessed play areas at 22 childcare centers in Adelaide, found that exposure to a diverse range of soil bacteria could be key in fostering a healthier childhood.

The research, led by Associate Professor Martin Breed from the College of Science and Engineering, emphasizes the importance of biodiversity in urban environments. Published in the journal Science of The Total Environment, the study highlights that well-vegetated play areas harbor more diverse soil bacteria, which could be beneficial for children’s health.

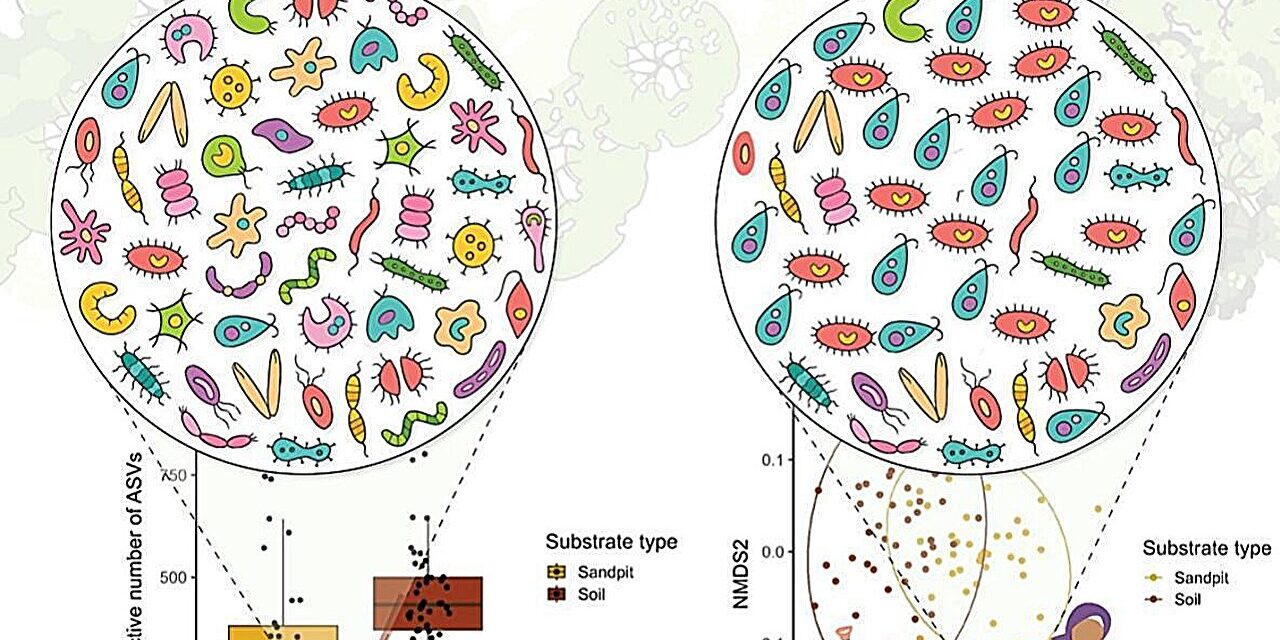

Interestingly, the study revealed that sandpits, often a staple in playgrounds, have distinct bacterial communities with lower diversity compared to other soils, including garden beds, mud-play areas, and lawns. “We found that sandpits had distinct bacterial communities and lower diversity than soils,” says Associate Professor Breed. This suggests that the type of substrate and the surrounding vegetation play a significant role in the microbial diversity children are exposed to.

Natalie Newman, the first author of the study and now an environmental scientist, points out that these findings open up possibilities for managing play area conditions to improve children’s exposure to beneficial bacterial communities. “There is great potential to manage these factors to improve children’s exposure to health-associated bacterial communities at a critical time in their immune system development,” she says.

The study’s implications are significant, particularly in light of urbanization trends. By 2050, it is projected that 70% of the global population will live in urban areas, leading to reduced interaction with biodiverse environments. This shift has been linked to weaker immune systems and a rise in health issues such as asthma and anxiety.

Dr. Jake Robinson, a co-author of the study, notes that while there is mounting evidence connecting human health to exposure to green and blue (aquatic) spaces, the exact mechanisms remain unclear. “We are seeking more evidence and possible frameworks to map the links between biodiversity and our health,” he says.

The researchers advocate for policies that promote native biodiversity and ecosystem restoration as public health interventions. “This should include greater consideration of integrating the health benefits from biodiversity when implementing nature-based solutions and promoting reciprocity with the land,” they conclude.

The study, titled Childcare centre soil microbiomes are influenced by substrate type and surrounding vegetation condition, offers a compelling case for rethinking how we design urban play spaces to support children’s health.

For more detailed information, the full study can be accessed in the journal Science of The Total Environment.