As the saying goes in aging research, “The best thing you can do to live longer is to choose good parents.” The idea that genetics plays a key role in lifespan is not new—people with long-lived parents and grandparents often live longer themselves, suggesting that longevity might run in families. However, lifestyle factors like diet and exercise also undeniably impact health and longevity. A recent study published in Nature sheds new light on the complex interplay between genes and lifestyle in determining lifespan.

The Role of Caloric Restriction and Genetics

Scientists have long known that reducing calorie intake can extend the lifespan of various animals. The first observation came in the 1930s, when researchers found that rats fed fewer calories lived longer than those allowed to eat freely. Similarly, people who engage in regular physical activity tend to live longer. However, the direct link between specific genes and longevity has remained controversial—until recently.

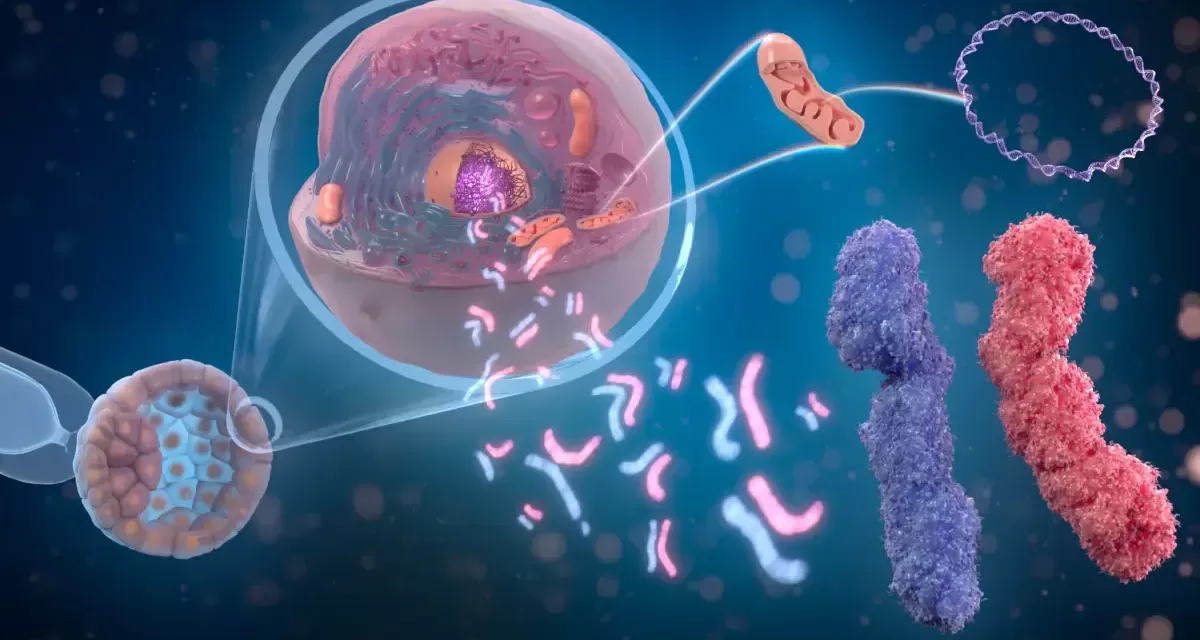

Cynthia Kenyon, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, discovered that altering a single gene in Caenorhabditis elegans (a tiny worm) could double its lifespan by changing how its cells responded to nutrients. This raised important questions: Which factor—genetics or lifestyle—plays a more critical role in longevity? And how do they interact?

To explore these questions, the Nature study examined 960 genetically diverse mice, focusing on various caloric restriction models. These included a reduction of either 20% or 40% in caloric intake compared to control groups, as well as intermittent fasting models where mice were denied food for one or two days at a time. The use of genetically diverse mice, rather than the genetically similar ones typically used in laboratory experiments, provided new insight into the effects of both diet and genetics on lifespan.

Key Findings: Genes Outweigh Dietary Restriction

The study’s findings were revealing. Genetics appeared to have a larger influence on lifespan than any dietary restriction models tested. Mice that were genetically predisposed to longer lifespans lived longer regardless of dietary changes, while those with shorter lifespans still benefited from dietary restrictions but could not catch up to their long-lived counterparts.

Caloric restriction, particularly at 40%, extended lifespan in all groups, with improvements in both average and maximum lifespans. However, the mice on the strictest diet also showed physical harms, such as reduced immune function and muscle mass loss. These side effects suggest that while caloric restriction can extend lifespan, extreme dieting may also come with health risks.

What Does This Mean for Humans?

While the study offers valuable insights into the biology of aging, it’s important to note that the findings in mice may not directly apply to humans. The study’s “unrestricted feeding” control group mimicked the effects of constant access to food, which doesn’t reflect typical human eating habits. Moreover, although the researchers did not control for exercise in this study, the mice on the 40% caloric restriction diet exercised significantly more, likely in search of food. This raises the question of whether the additional exercise, rather than just the diet, contributed to the lifespan extension.

Genes May Set the Limits, but Lifestyle Still Matters

Ultimately, the study suggests that our genes play a significant role in determining how long we can live, but lifestyle interventions—such as maintaining a healthy diet and exercising—can improve lifespan regardless of genetic background. Even though we can’t choose our parents or change our genes, the research indicates that making healthy lifestyle choices remains important for living a long, healthy life.

This study marks a critical step in understanding the balance between genetics and lifestyle in aging and longevity, offering hope that interventions targeting diet and exercise can enhance health outcomes for individuals of all genetic backgrounds.

Journal Reference: Nature