A groundbreaking study published in Cell today reveals that changes in the cervicovaginal microbiome may significantly contribute to a woman’s risk of acquiring chlamydia, a common and potentially severe sexually transmitted bacterial infection. Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have uncovered that bacterial vaginosis (BV), a condition affecting many women, consists of two distinct subtypes—one of which is a substantial predictor of chlamydia infection risk.

The study focused on young Black and Hispanic women, populations disproportionately impacted by both BV and chlamydia. These communities are historically understudied in medical research, making this large-scale study one of the most comprehensive of its kind.

“Bacterial vaginosis has long been associated with an increased risk of acquiring chlamydia, but until now, it wasn’t clear how the imbalances in the microbiome specifically contribute to this risk,” said Dr. Robert Burk, one of the study’s co-leaders and a professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “Our findings show that certain microbiome changes set the stage for chlamydia, and that targeting the more harmful BV subtype could potentially prevent many women from developing chlamydia.”

BV affects at least 30% of women and up to 50% of Black and Hispanic women. Studies show that young Black and Hispanic females are five times more likely to acquire chlamydia than their white counterparts, highlighting a pressing need for better healthcare solutions.

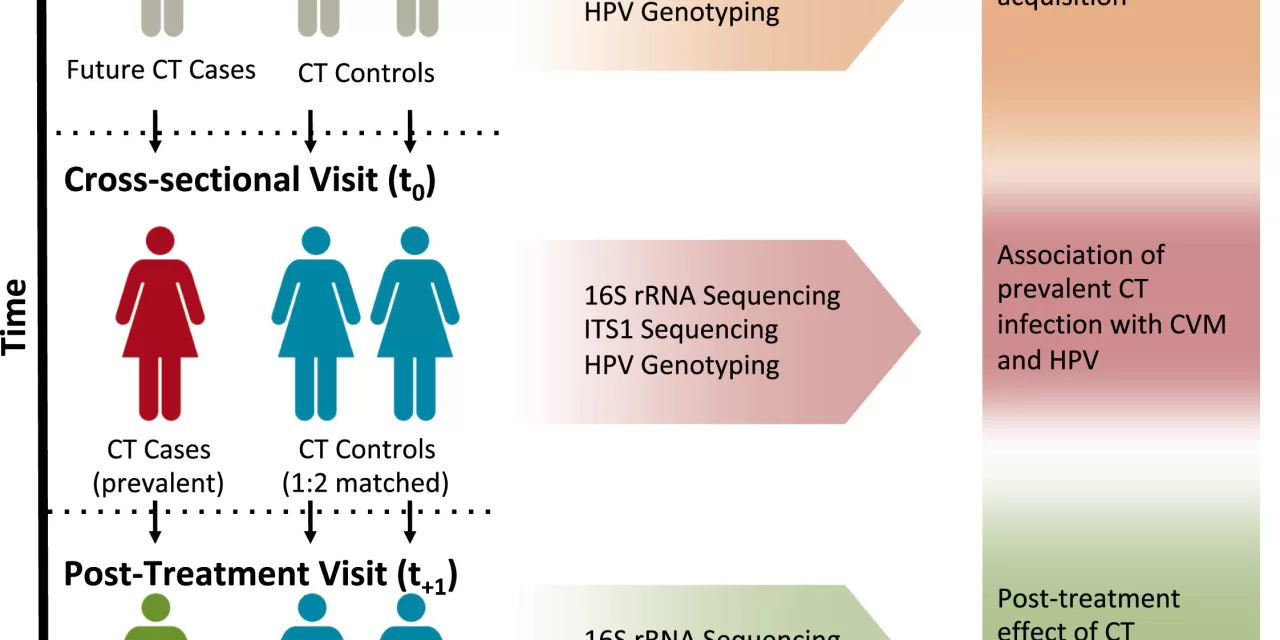

The researchers employed advanced DNA-sequencing technology to analyze the cervicovaginal microbiomes of 560 adolescent and young adult Black and Hispanic females, tracking their microbiome before infection, during infection, and after antibiotic treatment. This allowed them to identify the specific bacterial compositions linked to chlamydia infections.

Their results revealed that around 40% of BV cases belong to a subtype composed of ten interconnected bacterial types, which significantly increases the likelihood of chlamydia infection, reinfection, and even complications like pelvic inflammatory disease.

“This research furthers our understanding of BV’s role in increasing susceptibility to other infections, including chlamydia and human papillomavirus (HPV), which can cause cervical cancer,” said Dr. Nicolas Schlecht, another study co-leader from Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Our findings are part of a larger effort to understand how the cervicovaginal microbiome can influence both infection rates and cancer risks.”

The study’s authors argue that the findings could lead to a new approach in managing BV and chlamydia, particularly for underserved communities. Dr. Burk emphasizes the potential for microbiome analysis to become a regular part of clinical practice, similar to how high blood pressure is routinely monitored for cardiovascular disease risk. Identifying and treating high-risk cases of BV could greatly reduce the incidence of chlamydia and its serious health impacts, including infertility and miscarriage.

“This study shows that the seemingly benign condition of BV may actually be a major risk factor for chlamydia, much like how high blood pressure silently contributes to heart disease,” said Dr. Burk. “By regularly screening for BV, we could prevent the spread of chlamydia and other infections.”

Although advanced microbiome testing is not yet widely available, the researchers hope that, in the future, this technology could become more accessible, potentially even in home tests.

With additional authors including Mykhaylo Usyk, Christopher Sollecito, and Angela Diaz, the study represents a pivotal step toward better understanding the complex relationship between the microbiome, infections, and overall women’s health.

Reference:

Usyk, M., et al. “Cervicovaginal microbiome and natural history of Chlamydia trachomatis in adolescents and young women.” Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.12.011.