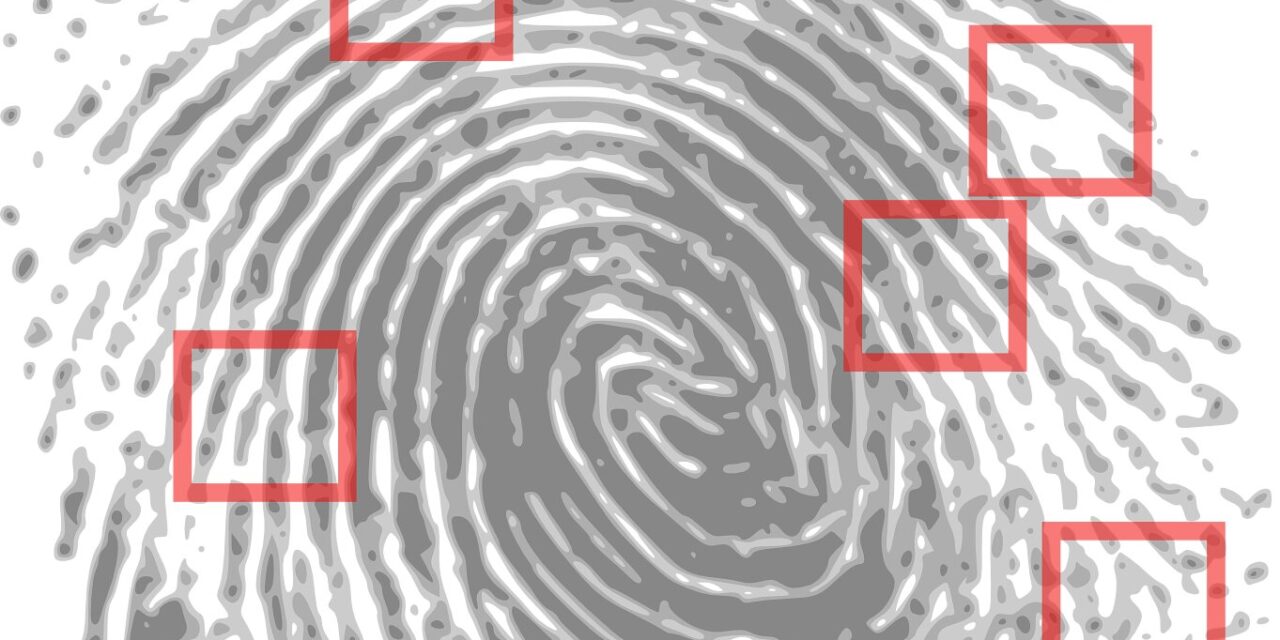

In a groundbreaking study published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, scientists from the University of Surrey have developed a method to detect antibiotics in fingerprints, offering a less invasive way to monitor tuberculosis (TB) treatment adherence. This innovative approach promises to aid the fight against drug-resistant TB by ensuring patients are taking their prescribed medication.

Traditionally, blood tests have been the gold standard for detecting drugs in the system. However, the new study reveals that finger sweat can provide results nearly as accurate as blood tests. Professor Melanie Bailey, an analytical chemist and co-author of the study, highlighted the significance of this development: “Now we can get results that are almost as accurate through the sweat in somebody’s fingerprint. That means we can monitor treatment for diseases like tuberculosis in a much less invasive way.”

TB is curable with a strict regimen of antibiotics. However, non-adherence to the full course of treatment can result in drug-resistant TB. The ability to monitor patient compliance through a simple fingerprint test could significantly improve treatment outcomes. The study, conducted on ten TB patients at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) in the Netherlands, demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of this method.

Dr. Onno Akkerman, a pulmonary physician at UMCG with a focus on tuberculosis, described the simplicity of the sample collection process: “We asked patients to wash their hands, put on a nitrile glove to induce sweating, and then press their fingertips onto a paper square. Finger sweat can be collected without any specialist training. Unlike blood, it isn’t a biohazard, so can be transported and stored much more easily.”

The samples were analyzed using mass spectrometry at Surrey’s Ion Beam Centre, revealing that antibiotics were detectable in finger sweat with 96% accuracy. The metabolite, a substance produced by metabolizing the drug, was detectable with 77% accuracy. The drug itself was present in finger sweat between one and four hours after ingestion, while the metabolized version appeared best after six hours.

Dr. Katie Longman, another co-author from the University of Surrey, emphasized the practical benefits: “It’s much quicker and more convenient to do that using fingerprints rather than taking blood. This could ease the time pressure on a busy health service and offer patients a more comfortable solution. For some patients, like babies, blood tests are not feasible or desirable—so techniques like this one could be really useful.”

This study not only opens the door to more convenient and less invasive drug monitoring for TB but also holds potential for monitoring other medications. The collaboration between the University of Surrey and UMCG sets a promising precedent for future research and application in medical diagnostics.

For more detailed information, refer to the study: Measurement of isoniazid in tuberculosis patients using finger sweat with creatinine normalization – a controlled administration study, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2024.107231.