Date: January 18, 2024

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the Penn Medicine Center for Genetics of Complex Disease has identified previously unknown genetic variants contributing to primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally. Published in Cell, the study focused on 11,275 individuals of African descent, a population disproportionately affected by this hereditary disease.

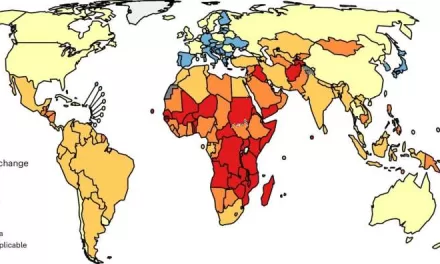

Glaucoma affects up to 44 million people worldwide, with individuals of African ancestry facing a fivefold higher risk of developing the condition and up to 15 times greater likelihood of experiencing vision loss or blindness compared to those of European ancestry. The lack of understanding of the genetic underpinnings in this population has limited the development of precise treatments for the disease.

Joan O’Brien, MD, Director of the Penn Medicine Center for Genetics of Complex Disease, emphasized the urgency of addressing glaucoma’s impact on the African ancestry population. With the support of a $17.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, the research aimed to unravel the genetic factors contributing to the neurodegenerative process in glaucoma, potentially paving the way for precision medicine.

Community involvement played a crucial role in the success of the study. Glaucoma specialists of African ancestry, along with Black community leaders in the Philadelphia area, collaborated to enhance enrollment and build trust within the community. The study utilized various strategies, including organizing glaucoma screenings in churches and senior centers, partnering with a Black-owned radio station for awareness campaigns, and offering free screenings with complimentary meals.

The research involved 11,275 participants, including 6,003 individuals with glaucoma and 5,272 controls. Genome-wide association studies and genetic analysis revealed two novel gene variants, rs1666698 (associated with DBF4P2) and rs34957764 (linked to ROCK1P1), implicated in glaucoma formation. Additionally, a third variant, rs11824032 (linked to ARHGEF12), was identified and previously associated with glaucoma severity.

Comparisons with results primarily featuring people of European descent highlighted the increased prevalence of these variants in individuals of African ancestry. The study emphasized the importance of diversity in genetic research, noting that focusing on this specific ancestry group uncovered unique insights critical to enhancing understanding of the genetics behind POAG.

The researchers validated their findings using the Penn Medicine BioBank, an extensive repository of genetic information linked to health records. The BioBank’s diverse collection of genetic material provided a valuable resource for the study, aiding in the validation of genetic effects observed in the initial cohort.

Marylyn Ritchie, PhD, director of the Institute for Biomedical Informatics at UPenn, underscored the significance of the BioBank in supporting the research. The team is now concentrating on developing improved methods for early glaucoma diagnosis and treatment. Using the identified variants, a polygenic risk score was created, outperforming similar scores based on European ancestry data.

The study’s impact extends beyond glaucoma research, as the genetic database is shared with researchers studying diseases that disproportionately affect African ancestry populations. The collaborative efforts aim to address health disparities and encourage more research on historically understudied populations.