Scientists at Rutgers Health have made a groundbreaking discovery that could revolutionize asthma diagnosis and management. Researchers have identified a simple blood test that could not only diagnose asthma but also assess its severity, offering hope for more accessible and accurate care for the millions of people affected by the disease.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, revealed that individuals with asthma exhibit significantly higher levels of a molecule called cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in their blood—sometimes up to 1,000 times higher than in healthy individuals. This finding could pave the way for a more straightforward diagnostic tool, especially in younger patients who struggle with traditional lung function tests.

“For decades, we believed that the enzyme phosphodiesterase was the key to reducing cAMP levels in the body,” said Reynold Panettieri, a senior author of the study and vice chancellor for Translational Medicine and Science at Rutgers University. “Our discovery challenges that idea, revealing that a specific transporter protein on the membrane of airway smooth muscle cells allows cAMP to leak into the bloodstream.”

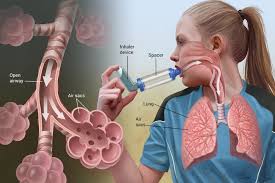

This discovery has profound implications for the roughly 1 in 20 Americans living with asthma. Current methods for diagnosing the condition, such as sophisticated breathing tests, can be difficult for young children, especially those under the age of five. The new blood test could offer a solution, making asthma diagnosis easier and more accessible.

“It’s really challenging to perform lung function tests on children under five,” explained Panettieri. “Our data suggests that a simple pinprick blood test could be used to diagnose asthma in kids who are unable to undergo conventional testing.”

The research team analyzed blood samples from 87 asthma patients and 273 healthy participants, finding consistently higher cAMP levels in those with asthma. These levels also correlated with disease severity, suggesting that cAMP could serve as a valuable marker for monitoring asthma over time.

This new discovery could be particularly important for urban areas, where asthma rates are significantly higher. “In cities, about 1 in 15 people has asthma,” said Panettieri. “It’s the number one reason kids visit the emergency room.”

In addition to its potential for improving diagnosis, this discovery may also lead to new treatment approaches. Asthma medications like albuterol work by increasing cAMP levels in airway smooth muscle cells, helping to relax the muscles and open the airways. By targeting the newly identified transporter protein, researchers hope to prevent the loss of cAMP, potentially improving the efficacy of current treatments.

“Future therapies could focus on preserving cAMP in the airways, which might make existing medications more effective,” said Steven An, a professor of pharmacology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and the study’s first author.

The researchers are collaborating with companies to develop a point-of-care test that could be used in doctors’ offices. Although initial attempts to create a simple lateral flow test, similar to a pregnancy test, did not prove sensitive enough, the team is optimistic about future developments using more precise fluorescent markers.

“We expect to finalize the test’s design within the next six months, secure intellectual property, and potentially see the test available within one to two years,” said Panettieri.

Looking ahead, the research team plans to study larger groups of asthma patients to better understand how cAMP levels relate to different subtypes of the disease. This could ultimately lead to more personalized treatment plans for asthma patients, ensuring that they receive the most effective care based on their individual needs.

While existing treatments, such as inhaled steroids and bronchodilators, are effective for many patients, asthma remains poorly controlled in others. The development of this blood test could provide doctors with a more precise tool for identifying patients who need more aggressive treatment and for tracking their response to therapy.

As researchers continue to explore this promising discovery, it could transform both the diagnosis and treatment of asthma, improving the quality of life for millions of individuals affected by the disease.

For more information on the study, see the article: Steven S. An et al, Serum cAMP levels are increased in patients with asthma, Journal of Clinical Investigation (2024). DOI: 10.1172/JCI186937.