Who hasn’t experienced the irresistible urge for dessert even after a hearty meal? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research have now uncovered the biological basis for this phenomenon, often referred to as the “dessert stomach.” Their findings, recently published in the journal Science, indicate that the same nerve cells responsible for satiety also drive our craving for sweets.

The Study: A Look at the Brain’s Role in Sugar Cravings

To explore why we continue to crave sweets despite feeling full, researchers studied the reactions of mice to sugar. Their experiments revealed that even satiated mice eagerly consumed desserts. Brain scans showed that a specific group of nerve cells, known as POMC neurons, became active when the mice encountered sugar, further stimulating their appetite.

Interestingly, when these mice consumed sugar, their brains released both satiety-inducing signals and a naturally occurring opioid called ß-endorphin. This compound interacts with opiate receptors in the brain, generating a reward sensation that encourages continued sugar consumption—even beyond satiety.

This effect was unique to sugar. Other types of food, such as fatty or standard meals, did not activate this opioid pathway. However, when scientists blocked the pathway, satiated mice stopped eating additional sugar, suggesting that this brain mechanism is specifically linked to sugar cravings in already-full individuals.

What About Humans?

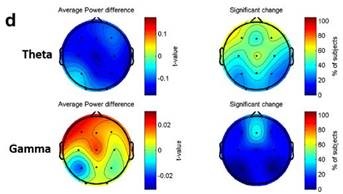

To determine whether this mechanism extends to humans, the researchers conducted brain scans on volunteers who were given a sugar solution. They found that the same brain region activated in response to sugar, indicating that humans share this neural circuitry with mice.

“From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense: sugar is rare in nature but provides quick energy. The brain is programmed to control the intake of sugar whenever it is available,” explained Henning Fenselau, the study’s lead researcher.

Implications for Obesity Treatment

These findings could have significant implications for treating obesity. While some existing medications block opiate receptors to curb overeating, their effectiveness in weight loss remains limited compared to appetite-suppressant injections. Researchers believe that combining these drugs with other therapies may provide better outcomes, though further studies are necessary.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a healthcare professional for personalized dietary and health recommendations.

For further details, refer to the original study: Marielle Minère et al, Thalamic opioids from POMC satiety neurons switch on sugar appetite, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adp1510.